When you step outside on a clear night, the sky becomes a map of stories, seasonal markers and navigation aids used by cultures around the world. Different societies have grouped stars into patterns that reflect local geography, mythology and practical needs, so the constellations you learn about depend on where and when you look.

There are 22 Types of Constellations, ranging from Aboriginal Australian constellations to Zodiac; for each entry the table lists Examples,Visibility / Where seen,Notable features — you’ll find below.

How do different cultures decide what counts as a constellation?

Cultures group stars by pattern, purpose and meaning: some emphasize lines and figures, others connect bright stars into practical markers (like navigation or calendars), and many include deep mythological context. The result is a range of types based on use, storytelling and sky visibility.

Can I see all these types of constellations from one place on Earth?

No — what you can see depends on your latitude, the season, and local light pollution. Some types are region-specific (for example, Indigenous sky traditions), while others like the Zodiac cross many latitudes; check the Visibility / Where seen column below for specifics.

Types of Constellations

| Type | Examples | Visibility / Where seen | Notable features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zodiac | Aries | Both hemispheres; along ecliptic; individual constellations best seen in different seasons | 12 constellations along Sun’s path; tied to ecliptic |

| Circumpolar | Ursa Major | High latitudes; never sets above certain latitudes (polar regions year‑round) | Never sets for given latitude; rotates around pole |

| Seasonal | Orion | Both hemispheres; prominent in specific seasons (e.g., winter northern skies) | Rise/set with seasons; good seasonal sky markers |

| Asterisms | Big Dipper | Wide; depend on asterism (Big Dipper: northern; Southern Cross: southern) | Informal star patterns inside/among constellations |

| IAU 88 constellations | Orion, Centaurus, Ursa Major | Whole celestial sphere; visibility depends on latitude/time | Officially defined boundaries covering sky |

| Classical (Ptolemaic) constellations | Leo, Scorpius, Perseus | Originally Mediterranean views; many visible in mid‑latitudes | Ancient Greek/Roman mythic groupings; 48 classical |

| Telescopic / Lacaille constellations | Microscopium, Telescopium, Caelum | Mostly southern sky; faint; best from mid‑southern latitudes | Small, faint, created for telescopes in 18th century |

| Southern constellations (Age of Discovery) | Pavo, Tucana, Grus | Southern hemisphere; best from mid‑southern latitudes | Many 16th–18th century European additions |

| Constellation families (Delporte) | Ursa Major family, Zodiac family, La Caille family | Vary by family; global distribution | Groups of related constellations by origin/proximity |

| Obsolete / historical constellations | Argo Navis, Quadrans Muralis, globus aerostaticus | Historical; no longer official; once visible from various latitudes | Removed, split, or renamed by modern standards |

| Chinese constellations | Three Enclosures, Twenty‑Eight Mansions | Visible across both hemispheres; historically tracked from East Asia | Lunar mansion system; alternate boundaries and names |

| Nakshatras (Vedic lunar mansions) | Ashvini, Bharani, Krittika | Along ecliptic; best seen according to each mansion’s longitude | 27/28 lunar divisions used in Vedic astronomy |

| Arabic/Islamic star traditions | Al‑Jawzaʻ (Orion) | Visible where constellation lies; historically across Islamic world | Rich star names and lore; influenced modern names |

| Babylonian constellations | Mul.APIN patterns (ancient lists) | Visible from Mesopotamia latitudes; historically seasonal | Earliest catalogues; lunar/solar calendrical links |

| Aboriginal Australian constellations | Emu in the Sky | Southern sky; prominent along Milky Way from Australia | Dark‑cloud constellations; cultural seasonal markers |

| Polynesian star navigation | Te Rā (Sun path) examples | Tropical Pacific; visible from island latitudes | Wayfinding via rising/setting stars and star lines |

| Native American constellations | Various tribal patterns (e.g., sky bear motifs) | Visible in respective continents; varies by tribal region | Distinct cultural interpretations; storytelling tied to landscape |

| Thematic categories (Animals, Humans, Objects) | Animal: Leo; Human: Hercules; Object: Telescopium | Global; thematic motifs appear in many cultures | Grouping by motif rather than position |

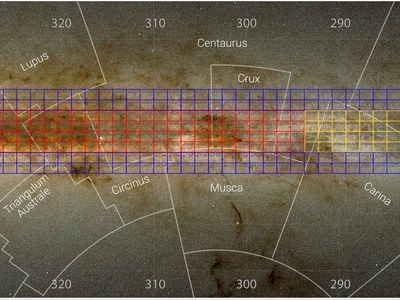

| Milky Way / Galactic‑plane constellations | Sagittarius, Cygnus, Crux | Along Milky Way; best in summer (northern) or winter (southern) | Rich star fields and deep‑sky objects |

| Northern constellations | Ursa Major, Cassiopeia | Northern hemisphere; best from mid‑northern to polar latitudes | Traditionally northern sky figures; navigation uses |

| Southern constellations | Crux, Centaurus | Southern hemisphere; best from mid‑southern to polar latitudes | Distinct southern star lore; many modern additions |

| Astrological zodiac (tropical vs sidereal) | Aries (tropical), Aries (sidereal) | Conceptual system used worldwide; not limited by latitude | Sign system for horoscopes; differing reference frames |

Images and Descriptions

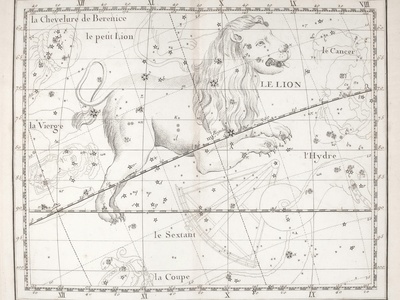

Zodiac

The zodiac is the band of constellations the Sun, Moon and planets travel through. Rooted in Babylonian/Greek astronomy, it’s central to celestial mechanics and astrology and helps locate planets and the Sun against familiar star backdrops.

Circumpolar

Circumpolar constellations never dip below the horizon at particular latitudes. Important for navigation and folklore, they slowly circle the celestial pole and remain visible all year from suitable latitudes, making them steady reference patterns.

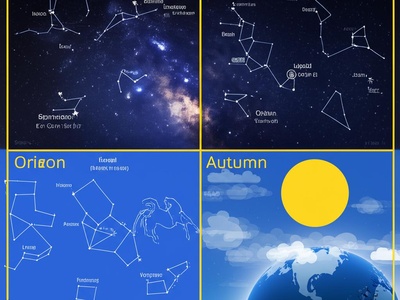

Seasonal

Seasonal constellations dominate the night sky at particular times of year and historically marked seasons for agriculture and navigation. Spotting them tells you the time of year at night and helps locate other stars and constellations.

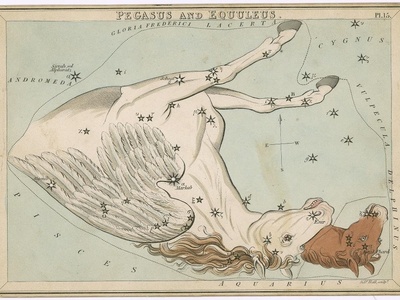

Asterisms

Asterisms are well‑known star patterns that may lie inside or span formal constellations. They’re popular for naked‑eye recognition—Big Dipper and Summer Triangle are practical orientation tools for casual observers and storytellers.

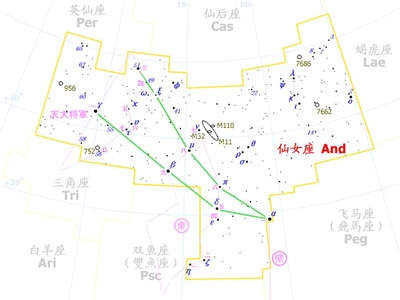

IAU 88 constellations

The IAU’s 88 constellations are the modern, internationally accepted divisions of the sky with precise boundaries. Adopted to standardize astronomy, they help astronomers name positions and catalog celestial objects consistently worldwide.

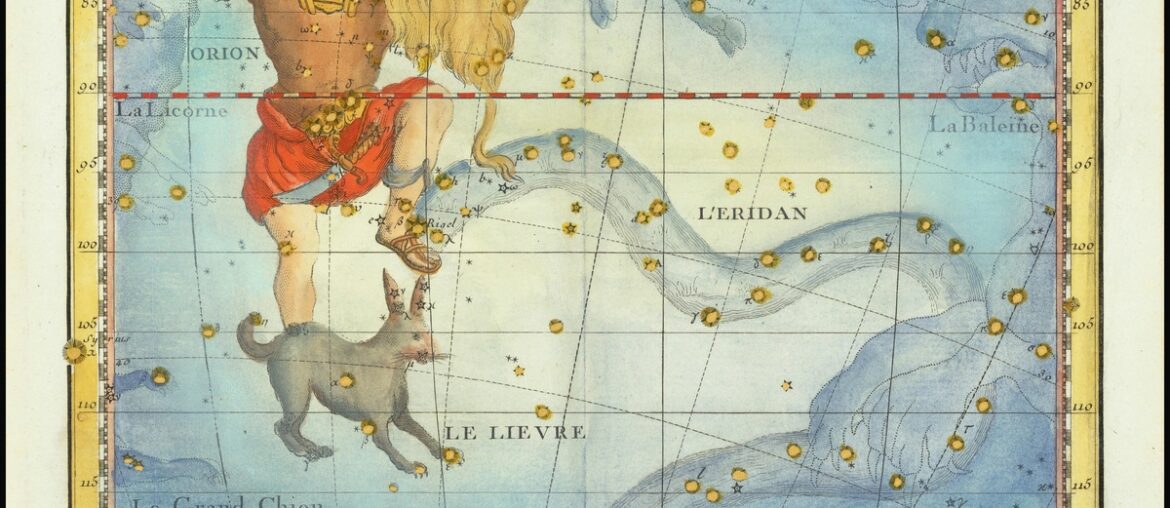

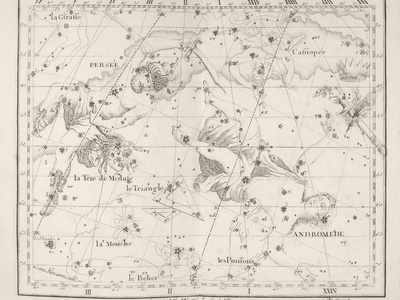

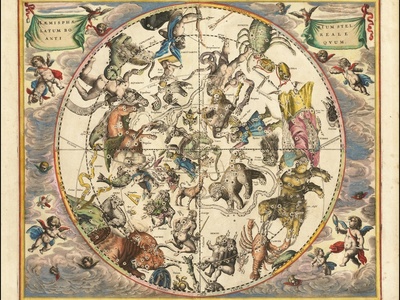

Classical (Ptolemaic) constellations

The Ptolemaic or classical constellations trace back to Greek and Roman star lore recorded in the Almagest. These mythic figures shaped Western celestial mapping and remain the core of many familiar star patterns.

Telescopic / Lacaille constellations

During the 17th–18th centuries astronomers introduced small, often instrument‑themed constellations to fill southern skies and denote faint stars seen through telescopes. They reflect scientific ages and practical charting of previously unseen southern regions.

Southern constellations (Age of Discovery)

Explorers and early modern astronomers mapped the southern sky and introduced many new constellations. These reflect Renaissance and navigational history and remain essential features for southern‑hemisphere stargazers.

Constellation families (Delporte)

Constellation families are practical groupings devised to organize constellations by mythic association, proximity, or origin (Eugène Delporte’s scheme). They help surveyors and learners remember clusters of related sky figures.

Obsolete / historical constellations

Obsolete constellations were once used by astronomers and navigators but later discarded or split by modern standardization. They reveal the evolving history of star charts and how cultural and scientific priorities changed.

Chinese constellations

Chinese constellations form a sophisticated sky system with the Three Enclosures and Twenty‑Eight Mansions. Independent from Western constellations, they were used for calendrics, astrology and imperial astronomy in East Asia for millennia.

Nakshatras (Vedic lunar mansions)

Nakshatras are the Vedic system of lunar mansions—27 or 28 ecliptic sectors used to track the Moon and for ritual calendars. They underpin traditional Indian astronomy and astrology, differing from Western zodiac boundaries.

Arabic/Islamic star traditions

Arabic and Islamic astronomical traditions preserved and enhanced star knowledge, contributing many star names and lore. Their scholarship bridged ancient Greco‑Roman, Indian and medieval European astronomy, leaving a lasting imprint on celestial nomenclature.

Babylonian constellations

Babylonian star lists are among the oldest recorded constellations and celestial schemes. They organized stars for calendars, omens and navigation, influencing later Greek star catalogs that shaped Western constellation traditions.

Aboriginal Australian constellations

Aboriginal Australian sky traditions often use dark dust lanes of the Milky Way as shapes (e.g., the Emu). These constellations are deeply integrated with seasonal cycles, ceremonies and cultural law across many Indigenous groups.

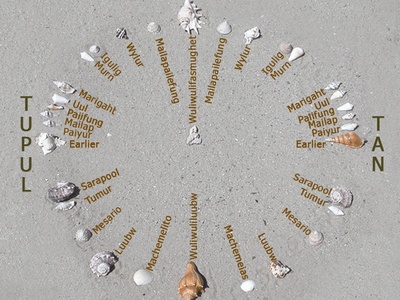

Polynesian star navigation

Polynesian navigation uses star lines and constellations as precise oceanic wayfinding tools. Patterns and names relate to routes, seasons and islands; knowledge is highly practical, transmitted orally for safe long‑distance voyaging.

Native American constellations

Native American peoples developed diverse constellation systems reflecting local landscapes, animals and stories. These star traditions guided seasonal activities, ceremonies and oral history, often differing markedly between tribes.

Thematic categories (Animals, Humans, Objects)

Thematic categories classify constellations by motif—animals, mythic people or man‑made objects. Themes show cultural priorities and storytelling choices, revealing why certain shapes were imagined and how societies relate to the sky.

Milky Way / Galactic‑plane constellations

Milky Way constellations lie along the galaxy’s bright band and host dense star fields, star clusters and nebulae. They’re favorite targets for visual observers and photographers and central to many cultural sky myths.

Northern constellations

Northern constellations refer to patterns mainly visible north of the celestial equator. They shaped navigation and myth in northern cultures and include many well‑known figures used for orientation and seasonal tracking.

Southern constellations

Southern constellations are those primarily visible south of the celestial equator. European exploration expanded catalogs of southern stars, while Indigenous southern cultures developed their own rich sky traditions distinct from northern lore.

Astrological zodiac (tropical vs sidereal)

The astrological zodiac maps twelve signs onto the ecliptic for horoscopic use. Tropical astrology fixes signs to seasons; sidereal astrology aligns signs with actual star constellations. It’s culturally influential though distinct from scientific constellation boundaries.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.