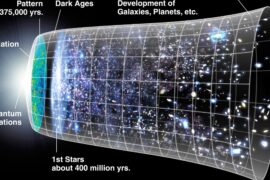

In 1998, two independent supernova teams found the universe’s expansion was accelerating — a discovery that led to the concept of dark energy and reshaped cosmology.

Earlier work — like Vera Rubin’s galaxy rotation-curve measurements in the 1970s — had already pointed to invisible mass that holds galaxies together: what we call dark matter.

Together these two unknowns make up roughly 68% (dark energy), 27% (dark matter), and 5% (ordinary matter) of the universe’s energy budget. The differences between dark matter and dark energy are central to why galaxies form the way they do and why the cosmos evolves the way it does.

Physical properties and observational evidence

This category covers how each phenomenon reveals itself in the sky and in maps of matter and energy. Transitioning from discovery to diagnostics, a few key datasets anchor our understanding: Vera Rubin’s rotation curves from the 1970s and gravitational-lensing maps for dark matter, and the 1998 Type Ia supernova results and Planck 2018 CMB measurements for dark energy.

1. Observable gravitational effects versus cosmic acceleration

Dark matter shows up as extra gravity inside galaxies and clusters: rotation speeds in spirals stay roughly flat with radius instead of falling off, which Rubin documented in the 1970s.

Gravitational lensing — for example the Bullet Cluster — maps mass that doesn’t line up with luminous gas, providing direct evidence that unseen mass exerts gravity independently of ordinary matter.

Dark energy, by contrast, was inferred from Type Ia supernova distance-redshift measurements in 1998 (work by Perlmutter, Riess, and Schmidt; Nobel Prize 2011) showing the expansion rate accelerates on cosmological scales. Planck’s 2018 CMB results then confirmed a cosmic composition consistent with a dominant, smooth energy component (Omega_lambda ≈ 0.68, Omega_matter ≈ 0.27).

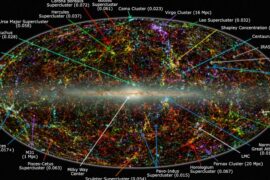

2. Distribution: clustered halos versus nearly uniform background

Dark matter clusters into halos and filaments that trace the cosmic web, while dark energy behaves like a nearly uniform background across observable space.

Large-scale structure surveys such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and the Dark Energy Survey map galaxies and their clustering, revealing the underlying dark-matter scaffolding. The Milky Way’s dark-matter halo is typically estimated at around 1×1012 solar masses, a concrete scale that shapes local dynamics.

By contrast the Planck CMB maps show small density fluctuations superimposed on a smooth energy density that drives global expansion rather than local binding. That contrast — clumpy mass versus smooth energy — is why one sculpts galaxies and the other influences cosmic-scale expansion.

Theoretical nature and candidate explanations

The differences between dark matter and dark energy show up again in theory: one is commonly modeled as particulate, the other as a property of space or a field. That split leads to very different research programs in particle physics and cosmology.

3. Particle-like candidates versus vacuum energy or fields

Dark matter is usually hypothesized to be made of particles or compact objects with mass and weak interactions. Leading candidates include WIMPs (weakly interacting massive particles) in the GeV–TeV mass range and axions with much lower masses targeted by resonant-cavity experiments.

By contrast, dark energy is most simply represented by the cosmological constant (Lambda): an intrinsic vacuum energy that creates negative pressure and accelerates expansion. Alternatives like quintessence treat dark energy as a dynamical scalar field with evolving density and pressure.

These choices matter: a detected dark-matter particle would point to physics beyond the Standard Model, while confirming a pure cosmological constant raises deep theoretical puzzles — notably the cosmological constant problem, where naive quantum estimates exceed the observed value by many orders of magnitude.

4. How they modify theory: gravity on small scales versus cosmic dynamics

In practice, dark matter enters cosmology as additional mass that enhances gravitational collapse and seeds structure, so it’s central to N-body simulations of galaxy formation in the Lambda‑CDM model.

Dark energy appears in the Friedmann equations as a term with negative pressure (or as Lambda), altering the universe’s expansion history and setting the late-time acceleration. If dark energy evolves, the expansion history and ultimate fate of the universe change.

Some researchers explore modified-gravity alternatives that replace dark components with changes to general relativity, but precision tests from lensing, clustering, and the CMB increasingly favor separate dark components as the simplest fit to data.

Experimental searches and practical implications

This category looks at how scientists try to detect or measure each phenomenon and at the broader consequences of either discovery. The methods differ radically: laboratory and collider searches for dark matter versus wide-field astronomical surveys for dark energy.

5. Scale of impact: galaxy-scale effects versus universe-scale consequences

Dark matter predominantly shapes galaxies and clusters: it explains flat rotation curves, stabilizes disks, and binds clusters together against the hot intracluster gas.

Dark energy governs the universe’s expansion and hence its fate. Its dominance at ~68% today sets the late-time acceleration rate and features in debates like the Hubble-constant tension — small, percent-level differences between local distance-ladder measurements and Planck CMB-based values.

If dark energy evolves (w ≠ −1), the long-term scenarios change: continued acceleration, a slowing expansion, or even more exotic fates become possible. That’s why measuring the equation-of-state parameter w is a priority.

6. Detectability: many targeted experiments versus observational cosmology campaigns

Dark matter has motivated direct-detection experiments and collider searches designed to spot rare particle interactions. Experiments such as XENON1T, LUX, and PandaX have steadily pushed down cross-section limits (notable results in 2018–2020), while axion searches like ADMX probe low-mass parameter space.

Dark energy is explored via precision cosmology: supernova programs, baryon acoustic oscillation measurements, weak lensing, and CMB missions. Projects include the Dark Energy Survey (DES), Euclid (ESA), the Rubin Observatory Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), and NASA’s Roman Space Telescope.

Progress has practical ripple effects: discovering a dark-matter particle would reshape particle physics and could inspire new technology, while tighter dark-energy constraints refine models of gravity and inform the ultimate cosmic timeline. Both paths rely on sustained, complementary investment in instruments and theory.

Summary

- Dark matter is clumpy and gravitationally attractive; dark energy is smooth and drives cosmic acceleration.

- We infer dark matter from kinematics and lensing (Vera Rubin, Bullet Cluster); we infer dark energy from supernovae (1998) and CMB/BAO measurements (Planck 2018).

- Theoretical paths diverge: particle candidates (WIMPs, axions) versus vacuum energy or fields (Lambda, quintessence).

- Experimental approaches differ: targeted lab/collider searches (XENON1T, ADMX) versus massive sky surveys (DES, Euclid, Rubin Observatory, Roman).

- Watch upcoming results from Euclid, Rubin/LSST, Roman, improved CMB analyses, and continued direct-detection campaigns — they’ll sharpen the 68%/27%/5% picture and may finally reveal what separates the two phenomena.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.