On April 10, 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration released the first-ever image of a black hole (M87*), a moment that reframed how we visualize the most extreme objects in the universe.

Why do these phenomena matter? Because they push physics, engineering and our curiosity to the limit: studying them refines cosmology, drives imaging and sensor technology, and often yields practical spin-offs for Earth. The wonders of deep space blend staggering scales with immediate technological payoffs, from new algorithms to better detectors.

Below are seven standout deep-space phenomena—each entry explains what it is, notes a striking fact or date, cites evidence or a statistic, and ties the observation to a concrete application or implication for science and everyday life.

Keep reading for a tour that ranges from titanic black holes and galaxy collisions to millisecond flashes and unannounced interstellar visitors. Two quick transitions: first, the grand, slowly changing landmarks; then the fast, energetic events; finally, the oddballs that missions chase up close.

Colossal Cosmic Structures

These are the grand, slowly evolving landmarks that shape galaxies and the large-scale web: from black-hole engines to colliding galaxies and vast star-forming nebulae. Studying them matters for cosmology and for advancing imaging techniques, from interferometry to adaptive optics. Typical scales run from millions to trillions of solar masses and distances of thousands to billions of light-years; upcoming surveys and simulations help connect observation to new technology.

1. Supermassive Black Holes (Sagittarius A*, M87*)

Supermassive black holes sit at galaxy centers and act as central engines that influence galaxy evolution. Our Milky Way’s black hole, Sagittarius A*, has a mass around 4 million solar masses, while M87* is billions of times the Sun.

Major milestones include the 2019 EHT image of M87* and the 2022 EHT image of Sagittarius A*—both made possible by very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) linking radio dishes around the globe. The Event Horizon Telescope’s VLBI network synthesized an Earth-sized aperture to resolve horizon-scale structure.

Those efforts pushed algorithms for image reconstruction and huge data pipelines: petabytes of radio data were correlated and processed, improving techniques now used in geodesy and telecommunications. Advances in GHz-band receivers and timing also benefit radar, satellite communications and precision Earth science.

2. Galactic Collisions and Massive Galaxy Clusters

Galaxy collisions sculpt structure over billions of years—our Milky Way and Andromeda are predicted to merge in roughly 4.5 billion years, reshaping both systems. On larger scales, galaxy clusters weigh in at about 1014–1015 solar masses and lie hundreds of millions of light‑years away.

Clusters like the Bullet Cluster provide compelling evidence for dark matter through gravitational lensing, observed with space telescopes (Hubble, Chandra) and ground arrays. Lensing maps let astronomers trace mass independent of light, constraining cosmological models.

Studying these systems demands large surveys and heavy data analysis, which in turn drives algorithmic work later reused in Earth remote sensing and automated image analysis. Simulations of galaxy mergers (including Milky Way–Andromeda scenarios) also refine numerical methods used across computational science.

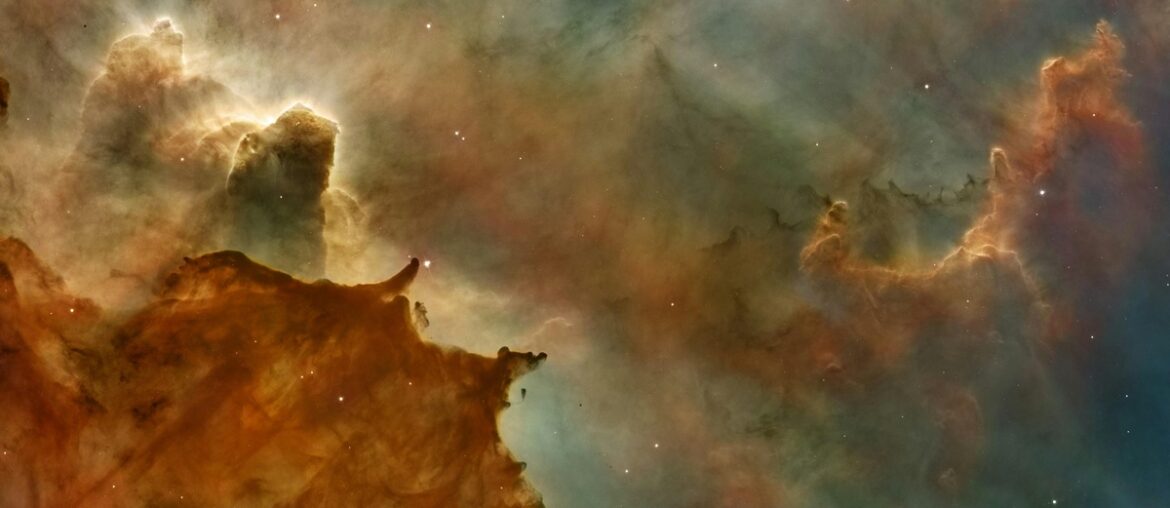

3. Nebulae and Star‑Forming Regions (Orion Nebula, Pillars of Creation)

Nebulae are stellar nurseries where gas and dust coalesce into new stars and planets. The Orion Nebula (M42) sits about 1,350 light-years away and spans many light-years, while features like the Pillars of Creation reveal dense, sculpted gas columns.

Hubble and JWST images have shown protostellar jets and planet-forming disks, providing direct evidence of early planetary system stages. Observations quantify star-formation rates and disk lifetimes across different environments.

The drive to image dusty nurseries pushed infrared detector development and adaptive optics; those technologies feed back into medical imaging sensors, night‑vision systems and materials research. In short, watching stars form refines instruments we use in other fields.

High‑Energy Phenomena and Dynamic Events

Short-timescale, high-energy events test physics in extreme regimes: relativistic jets, neutron-star collisions and magnetized stellar remnants pack energies unreachable on Earth. They’re crucial for fundamental physics and rely on fast-response networks and specialized detectors like LIGO and gamma-ray satellites.

Below are three dynamic phenomena that demand rapid observations and reveal the universe’s most violent processes.

4. Gamma‑Ray Bursts (GRBs) — The Briefest Beacons

Gamma‑ray bursts are the brightest electromagnetic events in the universe, lasting from milliseconds to minutes and releasing enormous energy—typical outputs range around 1044–1047 joules.

A standout case, GRB 080319B (in 2008), became briefly visible to the naked eye despite originating billions of light‑years away. GRBs trace both massive-star collapse (long GRBs) and neutron-star mergers (short GRBs), the latter connecting to gravitational-wave detections and multi-messenger astronomy.

Observing GRBs pushed development of fast data pipelines and rapid-alert networks (Swift, Fermi), improvements that translate to high-speed telemetry and alerting systems on Earth. High-energy detector technology advances have crossovers in radiation monitoring and particle detection.

5. Pulsars and Magnetars (Discovery and Extreme Magnetism)

The first pulsar (PSR B1919+21) was discovered in 1967 by Jocelyn Bell Burnell, opening a new branch of precision astrophysics. Pulsars are rapidly rotating neutron stars with rotation periods from milliseconds to seconds.

Magnetars are a related class with extreme surface magnetic fields often quoted as 1014–1015 gauss (around 1010–1011 tesla by SI units). A dramatic example, the giant flare from SGR 1806‑20 in 2004, briefly altered Earth’s ionosphere.

Pulsar timing underpins tests of general relativity and is being adapted for deep‑space navigation and timekeeping research. Radio-astronomy receiver improvements and signal-processing techniques developed for pulsar work have influenced communications and low-noise electronics.

6. Quasars and Active Galactic Nuclei (Powerhouses at Cosmic Distances)

Quasars are the extremely luminous cores of galaxies powered by accretion onto supermassive black holes and are visible across cosmological distances. The bright radio source 3C 273 was identified as a quasar in the 1960s, marking the discovery era for these beacons.

A key fact: astronomers now find quasars at redshifts z>6, letting us probe the universe when it was under a billion years old. Quasars act as backlights for studying the intergalactic medium and reionization.

Large quasar surveys (e.g., SDSS) and spectrograph advances have improved detectors and data pipelines used in other precision spectroscopy fields. Quasar catalogs also feed large-scale structure studies that refine cosmological parameters.

Exotic Objects and Targets for Exploration

These are the weird, compelling bodies that challenge classification and motivate missions: objects we can visit or detect up close, and that often yield surprises that reshape models. They’re among the practical wonders of deep space that spur mission planning and instrumentation.

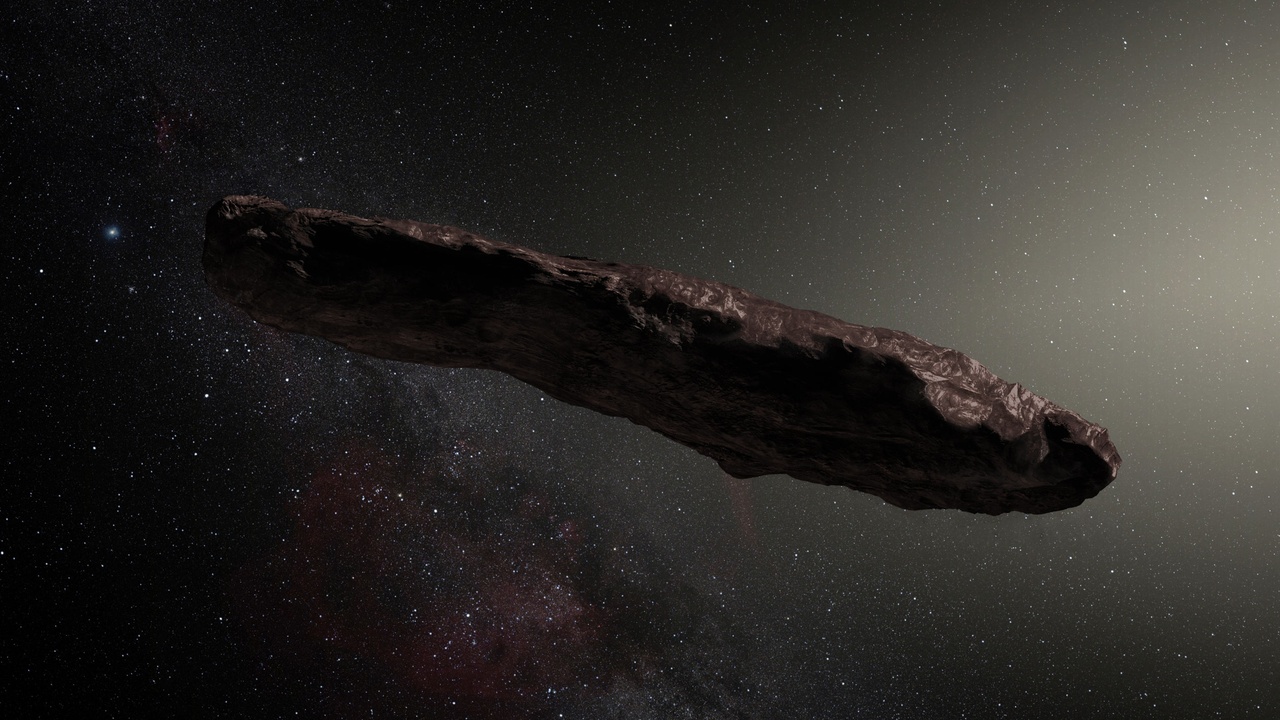

7. Rogue and Interstellar Objects (ʻOumuamua, 2I/Borisov, and Exotic Exoplanets)

Interstellar objects and rogue planets arrive from beyond our system or wander between stars. The first confirmed interstellar visitor, 1I/ʻOumuamua, was detected in 2017, followed by 2I/Borisov in 2019. Their trajectories and compositions offer direct clues about planet formation elsewhere.

Exoplanet discoveries progressed rapidly: the first planets around a pulsar were announced in 1992, and 51 Pegasi b—the first hot Jupiter around a Sun-like star—was found in 1995. Those milestones rewrote expectations for planetary systems.

These finds motivate sample-return concepts and rapid-response mission designs (for example, proposals to rendezvous with future interstellar objects) and push detection methods such as radial velocity and transit photometry. Citizen scientists and surveys like those enabled by New Horizons’ Kuiper Belt encounter in 2019 also play a role.

Summary

- Imaging a black hole in 2019 required global collaboration, VLBI and advanced algorithms—work that improved imaging, timing and data-processing techniques used beyond astronomy.

- Short, high-energy events such as GRB 080319B (2008) and neutron-star mergers force fast-response networks and better detectors, benefitting telemetry and detector design across disciplines.

- Interstellar visitors like 1I/ʻOumuamua (2017) and 2I/Borisov (2019) arrive unannounced and reshape priorities for mission planners and survey designers.

- Long-lived structures—supermassive black holes, galaxy clusters and nebulae—connect cosmology to practical tech advances in sensors, adaptive optics and computational methods.

- Follow upcoming facilities and missions (LIGO, JWST, Vera C. Rubin Observatory/LSST, future radio arrays) to see how the next wave of discoveries will change science and technology.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.