On July 20, 1976, NASA’s Viking 1 sent back the first clear images from the Martian surface — a moment that shifted Mars from a distant dot to a place with real, often baffling features. Those first horizon shots were flat and strangely familiar, and they set off decades of closer looks: orbiters mapped the whole planet, rovers drove into ancient riverbeds, and instruments began to tease apart the chemistry of soil and air.

Unexpected discoveries on another world grab our attention because they blend the poetic with the practical. Giant volcanoes and millimeter-scale concretions both tell a story about Mars’ past climate, tectonics, and potential for habitability, and they shape where we aim landers and humans next. This piece runs through ten of the most surprising and oddly evocative findings — clear descriptions, concrete numbers and dates, and why each one matters for planetary geology, astrobiology, and future exploration.

Readers curious about the quirks and mysteries of the planet will find everything from monster landforms to chemical whiffs that won’t go away. A few of the strange things found on mars are here too, placed into scientific context so you can see both the wonder and the reasoning behind each headline.

Geological oddities and giant landforms

Mars hosts planet-scale geology that looks almost unreal: the tallest volcanic edifice in the Solar System, canyon systems thousands of kilometers long, and microtextures only visible in HiRISE shots. Much of this mapping came from orbiters such as the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and instruments like HiRISE and MOLA, which together reveal both the huge and the tiny. Those landforms teach us about Mars’ thermal and tectonic history and help planners pick safe landing zones and resource-rich targets for future missions.

1. Olympus Mons — A 21.9 km-tall volcano

Olympus Mons is the tallest volcano and mountain in the Solar System, rising roughly 21.9 km above surrounding plains with a base nearly 600 km across. MOLA (Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter) mapped its summit and gave the precise elevation figures scientists use today.

It’s a shield volcano built by long-lived, low-viscosity lava flows; Mars’ lower gravity and lack of plate tectonics let a single hotspot build an immense, gently sloping edifice rather than migrate and form many smaller peaks (compare to Earth’s Mauna Loa and Everest for scale).

Studying Olympus Mons via MRO and HiRISE flank images helps volcanologists understand eruption durations and flow mechanics on other worlds — useful for comparative planetology and for modeling hazards when humans visit volcanic terrains elsewhere.

2. Valles Marineris — A canyon system 4,000 km long

Valles Marineris stretches about 4,000 km along Mars’ equator, with chasms plunging as deep as ~7 km in places — many times deeper than the Grand Canyon. Viking Orbiter mapping in the 1970s first revealed its astounding length; later MRO and THEMIS thermal imagery refined depth and structure measurements.

Formation hypotheses include large-scale tectonic fracturing followed by collapse and subsequent erosion by wind and possibly ancient fluids. The canyon system exposes crustal layers that let scientists probe Mars’ interior and search for minerals altered by past water.

Understanding Valles Marineris informs crustal stress models and helps identify strata that might preserve evidence of past habitable environments — important for selecting rover routes and sampling targets.

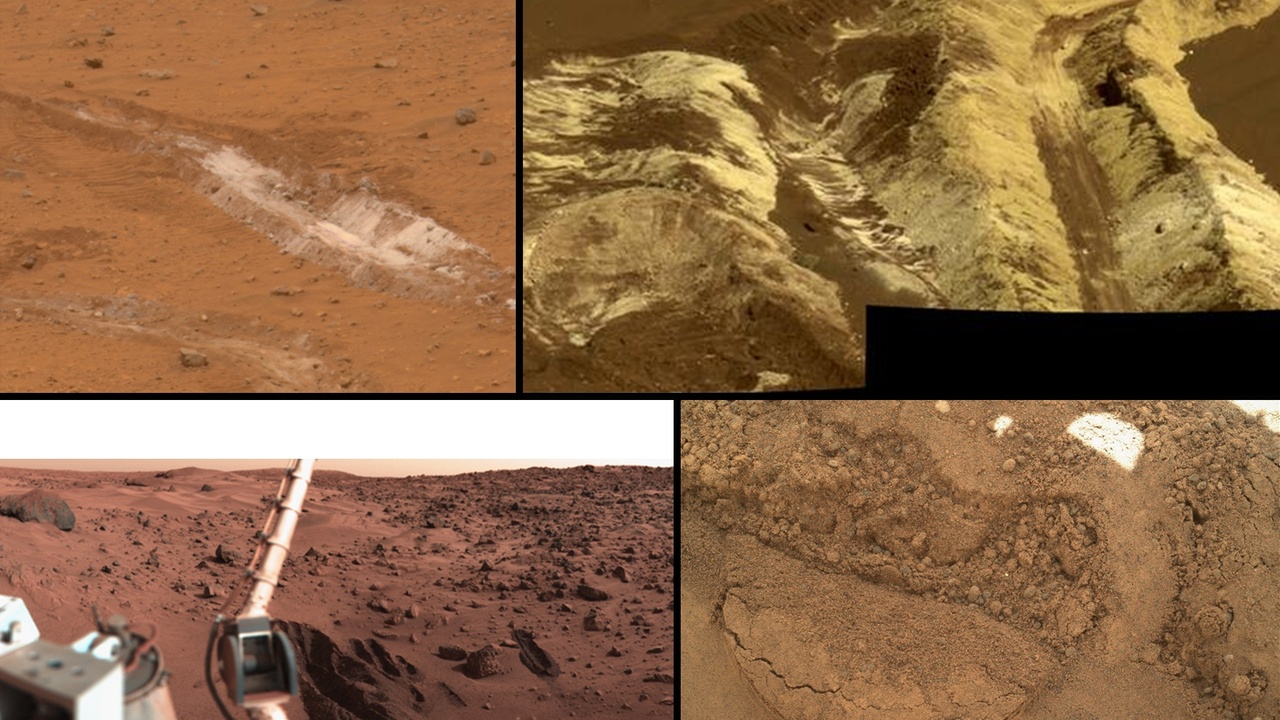

3. ‘Blueberries’ and hematite spherules — tiny but telling clues

Shortly after Opportunity landed in 2004, the rover found millimeter-scale, berry-like spherules composed largely of hematite. Their size — typically a few millimeters — and chemical signature (measured with the Mössbauer spectrometer and Mini-TES) pointed to concretions formed in wet sediments.

Those tiny spheres are powerful evidence that liquid water once altered rocks and soils at Meridiani Planum. Concretions like these help reconstruct local water chemistry and timing, and they guide sampling strategies for both present rovers and future sample-return priorities.

Active chemistry and seasonal surprises

Mars isn’t a static rock; its atmosphere and surface chemistry change with the seasons and sometimes produce transient signals that puzzle researchers. Orbiters and rovers — Curiosity and its SAM instrument, the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), and thermal imagers — track these temporal shifts, revealing processes that are active today.

Those seasonal and episodic chemical hints affect life-detection strategies, resource planning, and our view of Mars as a world that still evolves on human timescales.

4. Seasonal methane spikes — fleeting hints of activity

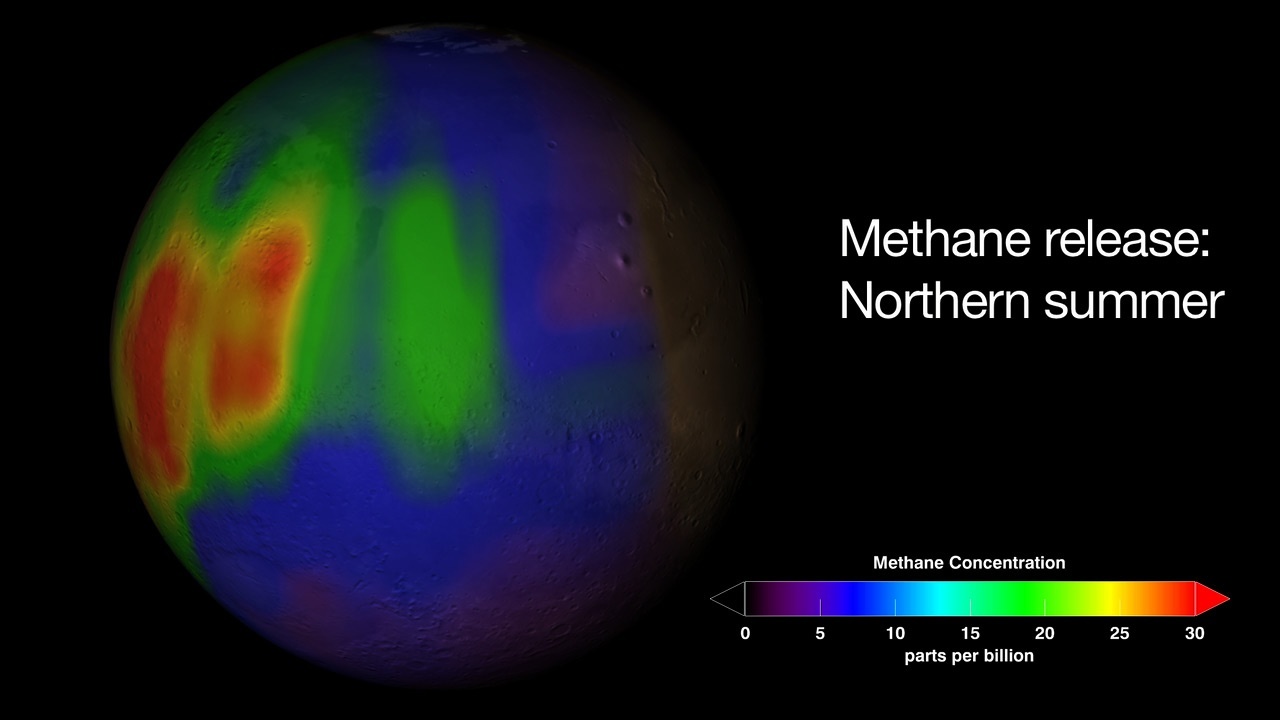

Measurements show a low methane background with occasional spikes that caught attention: Curiosity’s SAM instrument detected spikes up to about 7 parts per billion in 2013, while the Trace Gas Orbiter (launched 2016) has reported background levels down near fractions of a ppb.

Those differing numbers — surface rover spikes versus very low orbital detections — fuel active debate about sources. Proposed explanations range from geological serpentinization or release from clathrates to transient microbial activity in subsurface niches.

Methane shapes instrument design and mission planning: a reliable methane source would make specific life-detection experiments higher priority, and resolving the source requires coordinated ground and orbital campaigns.

5. Recurrent slope lineae (RSL) — dark streaks that grow seasonally

First widely reported from MRO imagery around 2011, recurrent slope lineae are narrow, dark streaks that appear on steep slopes and lengthen during warmer seasons, often extending tens to hundreds of meters.

Early interpretations favored briny liquid flows, but studies published in 2017–2018 shifted consensus toward dry granular flows in many cases, driven by temperature-dependent grain movement rather than flowing water.

RSL matter for planetary protection: if salt-stabilized brines occur in any locale, those sites would need strict handling rules to avoid contaminating potential habitats for native microbes.

6. Perchlorates and reactive soil chemistry

The Phoenix lander detected perchlorate salts in polar soil in 2008, and Curiosity later found reactive salts in Gale Crater. Perchlorates are chemically oxidizing and lower the freezing point of water, altering how water behaves in the near-surface.

Perchlorates complicate life-detection because they can destroy organic molecules during heating-based analyses (one explanation for Viking’s GCMS null result). At the same time, perchlorates offer both hazards and opportunities for human missions: they’re toxic to humans and need removal for habitats, but they can be processed as potential oxidizer feedstock for propellant.

Unsettling shapes and apparent artifacts

Humans are pattern-seeking by nature, and low-resolution lighting can turn a mesa into a face. Higher-resolution imaging and spectral data often resolve those mysteries, but a few geometric landforms genuinely reflect interesting geologic processes. Understanding pareidolia, camera geometry, and the limits of early data is part of good planetary science.

These apparent artifacts shape public reaction to missions and remind scientists to require repeat imaging and multiple data types before calling anything anomalous artificial.

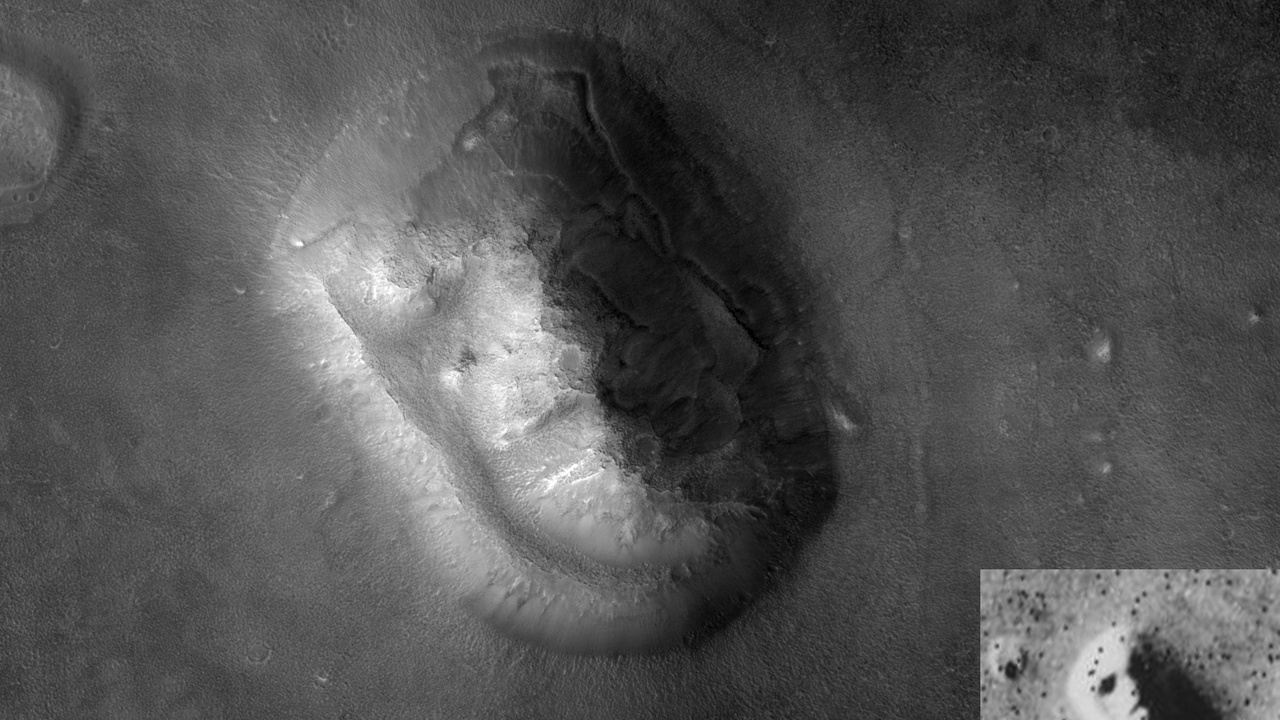

7. The ‘Face’ of Cydonia — pareidolia at work

The so-called Face on Mars appeared in Viking Orbiter images from 1976 as a face-like mesa in Cydonia. Low resolution and specific Sun angles produced shadowing that read as eyes and a nose.

Decades later, MRO/HiRISE re-imaged Cydonia at much higher resolution (2000s–2010s), showing a natural mesa with ridges and mesas but no sculpted features. The episode taught scientists and the public to be cautious with one-off low-res data before leaping to extraordinary conclusions.

8. Straight lines and geometric patterns — geology or something else?

Straight edges and polygonal patterns turn up in many HiRISE images. Natural processes — tectonic fractures, faulting, sedimentary layering, and thermal contraction that forms polygonal ground — can produce very linear or geometric patterns that look artificial at first glance.

Discriminating natural from non-natural requires high-resolution imaging plus spectral mapping (CRISM) to identify minerals and context. That protocol — see, re-image, and analyze composition — is the scientific route for testing extraordinary claims.

Surprising findings from landers and rovers

Ground truth from landers and rovers often confirms orbital hints — and sometimes complicates them. In-situ chemistry can yield ambiguous biology-like signals, uncover unexpected organics, or reveal instruments’ blind spots. Those surprises have reshaped instrument design and mission priorities.

Surface missions provide the context that orbital data lack: stratigraphy, texture, and fine-scale chemistry that tell a richer story about habitability and past environments.

9. Viking’s ambiguous biology experiments (1976) — puzzling positive results

In 1976 the Viking landers ran three biology experiments, including the Labeled Release (LR) test, which produced gas-release responses some argued looked like microbial metabolism. At the same time, Viking’s GCMS failed to detect organics in the same samples.

Later work suggested perchlorates in the soil could oxidize organics during Viking’s heating protocols, explaining the GCMS null result while leaving the LR response ambiguous. The disagreement forced later missions to design multiple, orthogonal tests and stricter contamination controls.

10. Organics, unusual carbon signals, and the promise of sample return

Modern rovers have found organics in multiple contexts: Curiosity reported organics in mudstones in 2018 (including chlorinated hydrocarbons and complex refractory organics), and Perseverance has been caching samples since its 2021 landing for eventual return to Earth.

Organics themselves aren’t proof of life, but they record environmental conditions and can preserve biosignatures if life ever existed. That’s why the planned Mars Sample Return campaign is such a big deal: lab instruments on Earth can do far more sensitive, varied analyses than flight hardware.

Those in-situ detections refine target selection and help ensure returned samples have the highest chance of answering whether Mars ever hosted biology.

Summary

- Mars surprises across scales: from Olympus Mons’ 21.9 km rise to millimeter hematite “blueberries,” each feature reveals part of the planet’s history.

- Active chemistry — seasonal methane spikes and perchlorate-rich soils discovered by Curiosity (2012 onward), Phoenix (2008), and orbiters — keeps the question of past habitability alive and informs instrument design.

- Apparent artifacts like the Cydonia “Face” demonstrate the need for high-resolution repeat imaging (Viking 1976 vs. MRO/HiRISE in the 2000s–2010s) and careful spectral analysis before extraordinary claims.

- Ground truth from landers and rovers — Viking, Opportunity, Curiosity, and Perseverance — has produced ambiguous biology tests and clear organic detections, making sample return a crucial next step for definitive answers.

- Follow ongoing missions (MRO, Curiosity, Perseverance, TGO) and the Mars Sample Return campaign to watch these puzzles unfold and to support the next generation of discoveries.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.