On August 15, 1977, a researcher at Ohio State University’s Big Ear radio telescope circled a line of printout in red ink and wrote a single word: “Wow!” The 72‑second spike at 1,420 MHz—the hydrogen line—registered an unusually high signal-to-noise ratio on the instrument’s paper record and never repeated. That brief moment of mystery captured the public imagination and still shows up in documentaries, lectures, and heated conversations about unexplained sky noise.

Unexpected radio blips matter because they point to new astrophysics, reveal gaps in our instruments or data handling, and sometimes turn out to be perfectly ordinary human-made interference. A single archival detection can spawn an entire subfield: the 2007 Parkes discovery of the Lorimer Burst led directly to specialized searches and new arrays such as CHIME and ASKAP.

Below are ten of the strangest, most influential, or most instructive radio events astronomers have logged, grouped into three buckets: historic mysteries, odd natural emitters, and local impostors plus planetary emissions. Each entry lists dates, instruments, what was measured, and why the example still matters.

Historic Mysteries: Signals That Defied Easy Explanation

Early radio telescopes such as Ohio State’s Big Ear and the Parkes Observatory turned up signals that didn’t match known astrophysical catalogs or local interference patterns. Those anomalies pushed institutions to formalize follow-up protocols, helped set priorities for SETI, and drove improvements in receivers and logging practices. The three examples below remain touchstones because they either never repeated or went on to launch new research programs.

1. The “Wow!” Signal (August 15, 1977)

The “Wow!” signal is one of radio astronomy’s best-known unsolved records. Detected at 1,420 MHz—the neutral hydrogen line—on August 15, 1977, it showed up on Big Ear’s printout as a strong, narrowband spike that lasted the telescope’s dwell time: roughly 72 seconds.

Jerry Ehman, the astronomer who noticed it, circled the sequence and wrote “Wow!” beside it. The printed intensity corresponded to a very high signal-to-noise ratio (often quoted informally as ~30 sigma on the record). Multiple re-observations by Ohio State, NRAO teams, and SETI groups failed to reproduce the signal from the same sky region.

Investigations considered satellites, atmospheric effects, and terrestrial interference but found no convincing culprit. The event drove better documentation practices and inspired proposals to re-survey the source region with modern dishes such as the Green Bank Telescope. No confirmed origin has been established, and the record remains tantalizing but unresolved.

2. The Lorimer Burst — First Fast Radio Burst (2007)

The Lorimer Burst was the first reported fast radio burst (FRB), discovered in 2007 by Duncan Lorimer and a student while mining archival Parkes data. It was a single, bright pulse about 5 milliseconds long with a dispersion measure (DM) near 375 pc cm−3, far above values expected from the Milky Way alone.

Because DM encodes the column of free electrons along the path, the high value suggested an extragalactic origin if intergalactic plasma provided the excess dispersion. At first some researchers suspected terrestrial interference, but subsequent searches uncovered more FRBs that shared similar properties.

The Lorimer Burst transformed an archival curiosity into a whole research area and motivated purpose-built surveys and instruments—CHIME, ASKAP, and purpose-written real-time pipelines—to catch and characterize millisecond transients across the sky.

3. FRB 121102 — The First Repeater (Discovered 2012)

FRB 121102 was first recorded in 2012 and later revealed to produce multiple bursts from the same sky location, making it the first known repeating FRB. Repeat activity was reported in 2015–2016, which allowed interferometers to localize the source precisely.

Very Large Array (VLA) and very long baseline interferometry tied the bursts to a star-forming dwarf galaxy at redshift ~0.193, roughly one gigaparsec away. The FRB sits near a compact, persistent radio source, suggesting a dense local environment.

Because repeaters aren’t one-off cataclysms, they ruled out some models and enabled coordinated multiwavelength follow-up that probes local conditions and emission physics. FRB 121102 reshaped how surveys allocate telescope time and seek host galaxies.

Odd Astrophysical Emitters: Natural Sources Behaving Strangely

Not every surprising radio signal is unexplained. Compact objects and magnetized planets produce emission with odd timing, extreme brightness, or unusual spectra. Improved time resolution and single‑pulse search methods revealed phenomena that challenge plasma theory and shed light on neutron star interiors.

4. Pulsars — Regular Beacons That Surprised Astronomers (1967)

Pulsars were discovered in 1967 by Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Antony Hewish as periodic radio pulses; the first known source, PSR B1919+21, had a period near 1.33 seconds. Early on, the regularity was so striking that some jokingly labeled the source “LGM” for “little green men.”

Pulsar periods span milliseconds (for recycled pulsars like PSR B1937+21) to several seconds. Their timing stability makes them precise cosmic clocks used in pulsar timing arrays (NANOGrav, EPTA) to search for gravitational waves and to test general relativity in strong fields.

Discovering pulsars reshaped neutron star astrophysics and sparked practical ideas—pulsar-based navigation and long-term timekeeping—while also underscoring how a simple radio survey can overturn expectations.

5. Rotating Radio Transients (RRATs) — Sporadic Pulses (2006)

RRATs were reported in 2006 by McLaughlin et al. as neutron stars that emit bright radio pulses only sporadically. Individual pulses can be separated by minutes to hours, so they often evade standard Fourier-based periodicity searches.

Examples like RRAT J1819−1458 show dispersion measures consistent with Galactic distances, indicating these are ordinary neutron stars with unusual emission behavior. Single-pulse search pipelines opened up this discovery space.

RRATs prompted revisions of the Galactic neutron-star census, since intermittency makes many objects harder to find, and they provided new constraints on magnetospheric switching and plasma instabilities.

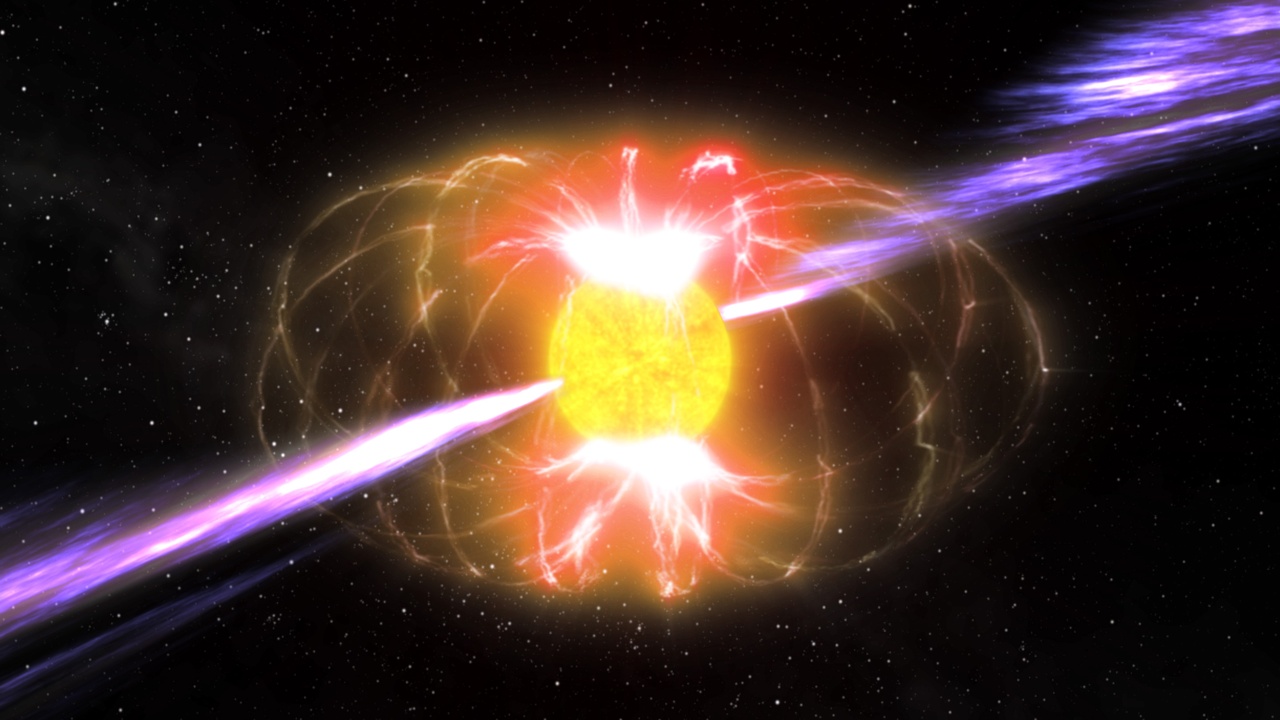

6. Magnetar Radio Bursts — SGR 1935+2154 Links to FRBs (April 2020)

On April 28, 2020, the Galactic magnetar SGR 1935+2154 produced an X-ray flare accompanied by a bright, millisecond radio burst detected by CHIME/FRB and independently by STARE2. The radio pulse’s phenomenology resembled that of low‑energy FRBs.

The burst’s energy was orders of magnitude below typical extragalactic FRBs but demonstrated that magnetars can produce FRB-like radio emission. Multiwavelength coverage tied the radio spike to contemporaneous high-energy activity.

That detection pushed magnetar models to the fore and motivated systematic magnetar monitoring programs to capture further coincident radio and X-ray events.

7. Crab Pulsar Nanoshots — Extremely Short, Extremely Bright Bursts

The Crab pulsar occasionally emits sub-microsecond structures—so-called nanoshots—observed with high-time-resolution backends at facilities such as Arecibo. Individual features have durations at the nanosecond scale and imply emission regions smaller than a meter.

Nanoshots reach phenomenal brightness temperatures and require highly coherent emission processes, pushing theoretical models of plasma behavior in the pulsar magnetosphere. Detecting them required sub‑microsecond sampling and careful instrumental calibration.

These observations probe extreme physics: how coherent radio waves form in a relativistic, magnetized plasma and how small-scale structures survive in such an environment.

Local Impostors and Planetary Radio: When Signals Aren’t What They Seem

Not every baffling radio blip comes from distant space. Observatories must separate terrestrial interference, planetary magnetospheric emissions, and solar bursts from true astrophysical transients. Each class teaches lessons about instrumentation, the near‑Earth environment, and magnetic interactions in the solar system.

8. Perytons — The Microwave Oven Mystery (Parkes, 1998–2011)

Perytons were short, dispersed pulses detected at the Parkes Observatory that initially looked like astrophysical dispersed signals because their frequency sweep mimicked interstellar dispersion. They appeared in multiple beams simultaneously, a red flag for a local origin.

Between the late 1990s and 2011, teams logged several perytons. In 2015 an on‑site experiment traced them to staff using microwave ovens—opening the oven door mid‑cycle produced a chirped broadband signal that the backend recorded as a dispersed pulse.

The peryton saga led to stricter radio‑frequency interference (RFI) protocols, better on‑site metadata (who was using which equipment and when), and an appreciation that human habit can masquerade as cosmic mystery.

9. Jupiter’s Decametric Emissions — Loud Planetary Radio

Jupiter has produced strong decametric radio bursts since the 1950s. Emission covers roughly 0.3–40 MHz and is modulated by the planet’s rotation and by the orbital phase of its moon Io, which injects plasma into Jupiter’s magnetosphere.

Spacecraft (including Juno) and ground arrays regularly record these bursts, which can be tens of kilowatts to megawatts in radiated power at source and are richly structured in time and frequency. Io-associated modulation patterns are a classic diagnostic.

Studying Jupiter’s radio output informs magnetospheric physics and helps develop techniques for searching for radio emission from exoplanets with strong magnetic fields.

10. Solar Radio Bursts — Powerful, Predictable, and Disruptive

The Sun routinely produces radio bursts tied to flares and coronal mass ejections; Type II bursts trace shock waves, and Type III bursts trace electron beams moving along open field lines. Frequencies span kHz to GHz depending on the mechanism and plasma density.

Major events, such as the 2003 “Halloween” storms, generated intense radio emission that interfered with HF communications and degraded GPS signals. Solar radio monitoring is therefore critical for space weather forecasting and for scheduling sensitive radio observations.

Solar bursts are a reminder that the nearest star is also one of the most important radio sources for observers on and near Earth.

Summary

- Historic puzzles like the 1977 “Wow!” printout still capture curiosity and underscore how a single anomalous detection can ripple through science and public interest.

- Archival finds such as the Lorimer Burst turned into a major field—fast radio bursts—and follow-up work (CHIME, ASKAP, FAST) now finds hundreds of events each year.

- Instrumental false positives, from perytons to misidentified terrestrial signals, taught observatories to tighten RFI controls and log more operational metadata.

- Natural sources—from pulsars and magnetars to Jupiter and the Sun—reveal extreme plasma physics across timescales from nanoseconds to minutes.

- Keeping an eye on new detections matters: strange radio signals from space continue to push technology and theory, so follow public releases from CHIME, ASKAP, NRAO, and NASA for the next surprise.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.