In 1687 Isaac Newton published Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica after reflecting on why the Moon and apples fall — a moment that tied a backyard observation to the motion of planets. That simple question opened up a way to see gravity as the invisible architect of the cosmos: it shapes planets and stars, controls orbital motion, influences habitability, and determines how we explore and use space. Newton’s insight still underpins modern astronomy and engineering (and yes, Earth’s surface gravity is about 9.8 m/s²). Pay attention to gravity’s fingerprints and you’ll start seeing them everywhere—from tides that shape coastlines to the reason spacecraft need precise fuel budgets. Below are ten concrete ways gravity affects large-scale processes, grouped into four approachable categories so you can jump to what interests you most.

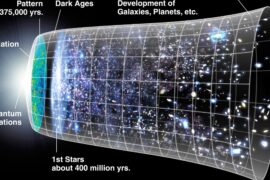

Formation & Structure in the Cosmos

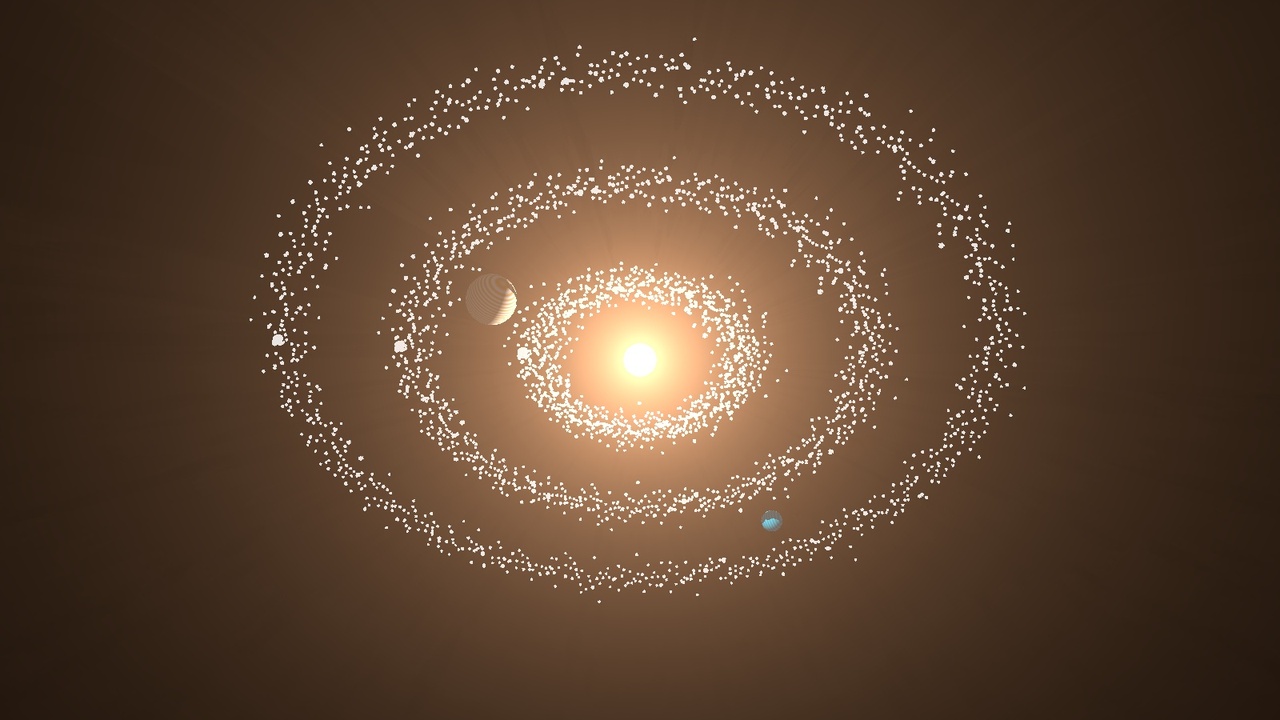

1. Gravity sculpts planets and enables accretion

Gravity pulls dust and ice together in protoplanetary disks, letting tiny grains stick, grow into planetesimals, and eventually build planets. ALMA images (for example HL Tauri) show gaps and rings where growing bodies are already shaping the disk.

Growth from millimeter grains to kilometer-scale planetesimals and then to protoplanets happens quickly on astronomical timescales—roughly 1–10 million years in many models—because mutual gravity and collisions accelerate accretion. Once an object has enough mass it can hold on to lighter material and concentrate heavier elements toward its core, which influences surface conditions long term.

Jupiter’s early rapid growth (by core accretion) probably helped clear the inner disk and set the architecture of the Solar System, while the asteroid belt contains leftover planetesimals that never merged into a full planet.

2. Gravity drives star formation from interstellar clouds

Cold molecular clouds collapse when gravity overcomes internal pressure—a process described by Jeans instability. Regions like the Orion Nebula are stellar nurseries where dense clumps contract into protostars under their own weight.

Typical collapse and protostar formation take on the order of 0.5–10 million years, depending on mass and environment. Over time, nuclear fusion ignites in the core and a new star (for example the Sun about 4.6 billion years ago) begins producing heavy elements that later seed planets.

Star formation rates shape galaxy evolution: more gravity-driven collapse means a younger, brighter stellar population; less means a quieter galaxy.

3. Gravity determines shape — round worlds vs. lumpy rocks

When a body’s self-gravity exceeds the strength of its materials, it relaxes into hydrostatic equilibrium and becomes roughly spherical. That transition typically happens for objects with diameters of a few hundred kilometers, though composition matters.

For example, the dwarf planet Ceres is about 940 km across and is spherical, while many asteroids (and small moons) like 243 Ida or 25143 Itokawa (∼535 m) remain irregularly shaped. This simple gravitational rule helps define categories such as planets and dwarf planets.

Orbital Motion & Dynamics

On scales from moons to galaxies, gravity defines orbital paths and speeds—understanding how gravity affects space means predicting those motions. Gravity provides the centripetal force that keeps bodies moving in ellipses, circles, or more complex paths as described by Kepler’s laws and Newtonian mechanics.

4. Gravity keeps planets and moons in stable orbits

Gravity supplies the centripetal force balancing an object’s inertia so it orbits rather than flying away. Kepler’s third law links orbital period and distance; Newton’s law tells us the force involved.

Earth orbits the Sun at about 29.78 km/s with a period of one year, and satellites rely on predictable gravity to stay aloft. Low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites like the ISS sit roughly 400 km above Earth, while geostationary satellites orbit at 35,786 km, where their orbital period matches Earth’s rotation.

Because gravity dominates, orbits are stable unless another force acts—atmospheric drag, thruster burns, or perturbations from other bodies. That predictability is why GPS and communications networks work.

5. Tides, tidal locking, and orbital resonances

Tidal forces come from gravity gradients across an object and produce tides in oceans, crustal flexing, and slow changes to rotation. The Moon’s pull causes Earth’s semidiurnal ocean tides, with typical coastal ranges of about 0.5–2 meters in many places.

Tidal torques can lock a moon’s rotation so one face always points to its planet (the Moon is tidally locked). Resonances also control orbital eccentricities—Mercury is in a 3:2 spin-orbit resonance, and Pluto–Charon are mutually tidally locked.

In some cases tidal heating is enormous: Io’s interior is flexed by Jupiter and neighboring moons, powering hundreds of active volcanoes and making Io the most volcanically active world we’ve observed.

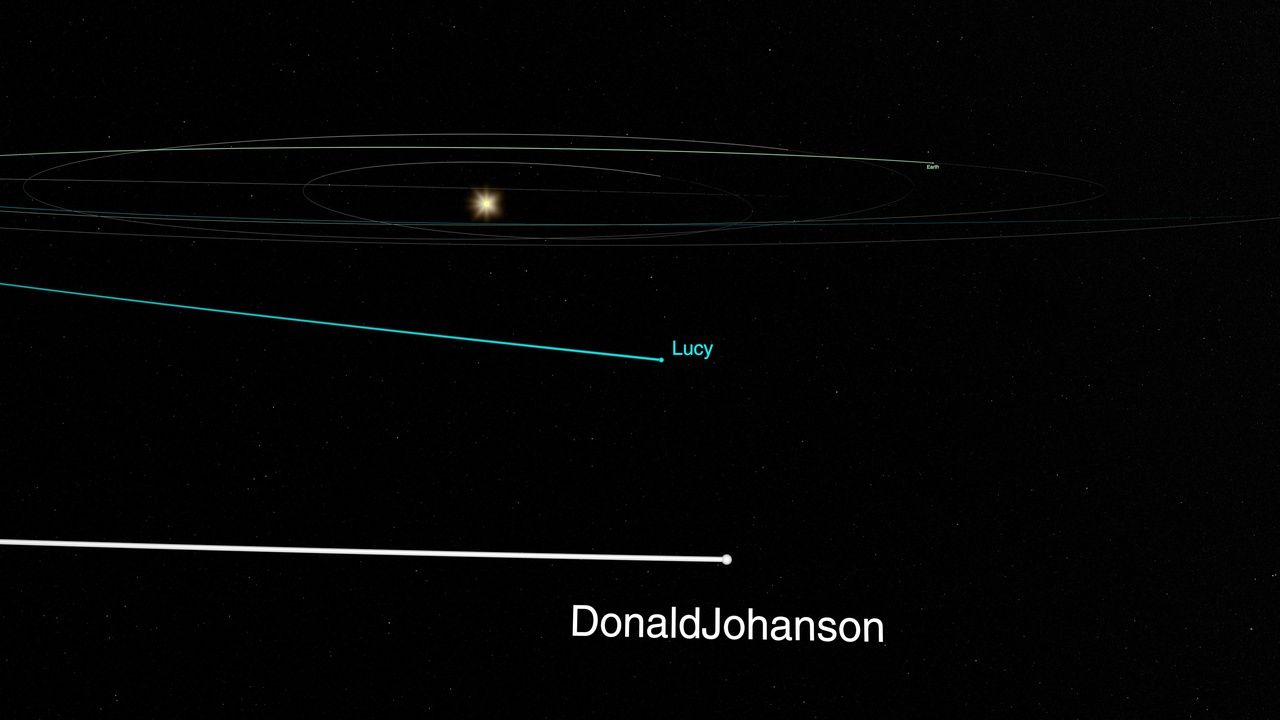

6. Gravity organizes collisions, captures, and clearings

Massive bodies alter trajectories of smaller objects through gravitational scattering, capture, or ejection. Jupiter, with a mass of about 1.898 × 10^27 kg, has a strong influence on comets and asteroids entering the inner Solar System.

Famous events like the Shoemaker–Levy 9 impact on Jupiter in 1994 show how gravity can capture and then break apart a comet before it collides. On the flip side, Jupiter’s perturbations also redirect objects toward Earth or fling them out of the system entirely.

Understanding these dynamics is central to impact risk assessment and planetary defense, and it informs missions aiming to rendezvous with or capture asteroids.

Thermal, Interior & Habitability Effects

Gravity not only moves things; it squeezes and holds them. Internal pressure, atmosphere retention, and tidal heating all hinge on gravity, which in turn affects whether a world might be habitable.

7. Gravity controls internal heating and geological activity

Self-gravity produces hydrostatic pressure that helps segregate a body into core, mantle, and crust. This differentiation concentrates heavy elements in cores and sets up conditions for magnetic dynamos when the core is molten and convecting.

Radioactive decay and tidal forces add heat; on some moons tidal heating can dominate radiogenic heating. Io, squeezed by Jupiter and orbital resonances, sustains intense volcanism with hundreds of active vents and continuous resurfacing.

That internal activity matters for habitability: a magnetic field generated by a convecting core helps shield an atmosphere from stellar wind, while tectonics and volcanism recycle chemicals needed for life.

8. Gravity sets atmosphere retention and the habitable zone

A planet’s gravity determines its escape velocity, which in turn controls how easily gases can leak to space. Earth’s escape velocity is about 11.2 km/s; a planet with much lower surface gravity struggles to keep light gases over geological time.

Mars has about 0.38 g and has lost much of its original atmosphere, contributing to its thin present-day air. By contrast, Titan retains a dense nitrogen atmosphere despite lower gravity because cold temperatures reduce thermal escape.

Gravity also interacts with stellar radiation to define habitable zones: whether a planet can maintain surface pressure and liquid water depends on both its distance from the star and its ability to hold an atmosphere.

Technology, Exploration & Practical Impacts

For engineers and mission designers, gravity is both the main barrier and the most useful tool. Knowing how gravity affects space lets teams compute delta-v budgets, plan gravity assists, and design missions to fit within launch constraints.

9. Gravity shapes mission design: launches, delta-v, and gravity assists

Escaping Earth’s gravity well is expensive: the theoretical escape velocity is 11.2 km/s, while practical delta-v to reach LEO is about 9.4–9.7 km/s once aerodynamic and steering losses are included. Those numbers drive rocket design and launch economics.

Engineers use Hohmann transfers for fuel-efficient trips and gravity assists to gain speed without propellant. Voyager 2 used flybys of Jupiter and Saturn to reach Uranus and Neptune—maneuvers that would have been prohibitively costly without those assists.

So gravity is a cost driver and an enabler: it makes some missions costly but also offers tricks to reach far-off targets.

10. Microgravity enables experiments, manufacturing, and scientific insights

Microgravity—continuous free-fall aboard stations like the ISS (~400 km altitude)—removes buoyancy-driven convection and sedimentation, revealing fluid and biological behaviors masked on Earth. That lets scientists grow purer protein crystals, study colloids, and test materials in new regimes.

Results have practical payoffs: better protein structures help drug design, and higher-quality fibers or 3D-printed components made in microgravity could someday yield commercial products. The ISS hosts dozens of experiments that aim to translate space results into Earth benefits.

Microgravity research also sharpens fundamental understanding of physics, which feeds back into engineering for life support, habitats, and long-duration exploration.

Summary

- Gravity organizes cosmic construction: it builds planets and stars, and sets when worlds become spherical (Ceres ~940 km vs. irregular asteroids).

- Tidal effects and orbital dynamics control everything from Earth’s tides to Io’s volcanism, and they determine impact risks and capture events (Shoemaker–Levy 9, Jupiter’s role).

- Gravity governs habitability by driving interior heat and magnetic dynamos, and by setting escape velocity—key factors in why Mars lost its atmosphere and why icy moons like Europa and Enceladus can host subsurface oceans.

- On the practical side, gravity defines launch costs and delta-v budgets, enables gravity-assist tours (Voyager), and creates microgravity conditions (ISS ~400 km) that enable unique science and commercial experiments.

- Keep an eye out for gravity’s effects in mission news, exoplanet reports, and Earth science—understanding how gravity affects space makes those stories clearer and often more surprising.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.