Comets have threaded the night sky for centuries, turning up in observatory logs, sailors’ stories, and backyard sketches. Watching their appearances side-by-side helps show how brightness and orbit vary across time and observing conditions.

There are 23 Great Comets, ranging from Arend–Roland,West (C/1975 V1) to more recent discoveries; for each entry the columns Year,Peak magnitude (mag),Orbit (period yrs) are provided — you’ll find below.

How is “peak magnitude” measured, and what does it tell me?

Peak magnitude is the brightest recorded apparent magnitude for a comet while it was observed; lower or negative numbers mean brighter objects. It depends on the comet’s distance from the Sun and Earth and the amount of dust/gas reflecting sunlight, so use it to compare observed brightness rather than intrinsic size.

Will any of these comets return, or are they one-time visitors?

Check the Orbit (period yrs) column: short-period values indicate comets that return on human timescales, while very long or undefined periods usually mean they won’t return for thousands of years or are essentially one-time visitors. The table below gives the period estimate for each entry.

Great Comets

| Name | Year | Peak magnitude (mag) | Orbit (period yrs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caesar’s Comet | 44BC | -4.00 | long-period |

| Halley’s Comet | 1066 | -1.00 | 76 |

| Great Comet of 1577 | 1577 | -1.00 | long-period |

| Great Comet of 1618 | 1618 | -2.00 | long-period |

| Great Comet of 1680 (Kirch) | 1680 | -2.00 | long-period |

| Great Comet of 1744 (C/1743 X1) | 1744 | -6.00 | long-period |

| Great Comet of 1811 (C/1811 F1) | 1811 | -0.50 | long-period |

| Great Comet of 1843 (C/1843 D1) | 1843 | -7.00 | long-period |

| Donati’s Comet | 1858 | -1.50 | long-period |

| Great Comet of 1861 (C/1861 J1) | 1861 | -1.00 | long-period |

| Great Comet of 1882 (C/1882 R1) | 1882 | -6.00 | long-period |

| Great Comet of 1910 (Halley) | 1910 | -1.00 | 76 |

| Ikeya–Seki | 1965 | -10.00 | parabolic |

| Bennett (C/1969 Y1) | 1970 | 0.00 | long-period |

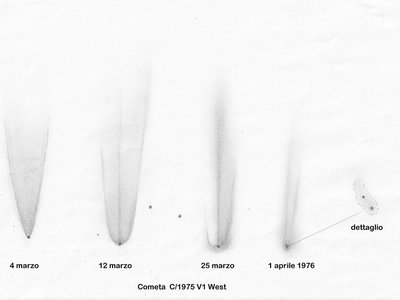

| West (C/1975 V1) | 1976 | -3.50 | long-period |

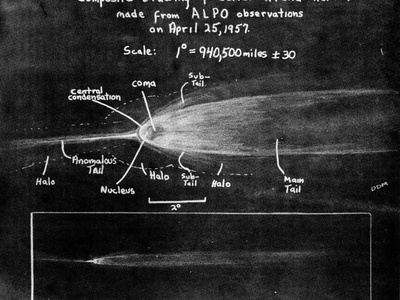

| Arend–Roland | 1957 | 1.00 | long-period |

| Hyakutake | 1996 | 0.00 | long-period |

| Hale-Bopp | 1997 | -1.00 | 2,533 |

| McNaught (C/2006 P1) | 2007 | -5.50 | long-period |

| Lovejoy (C/2011 W3) | 2011 | -3.50 | long-period |

| NEOWISE (C/2020 F3) | 2020 | 1.00 | long-period |

| Great Comet of 1844 (C/1844 Y2) | 1844 | -3.00 | long-period |

| Great Comet of 1680 (Second listing note) | 1680 | -2.00 | long-period |

Images and Descriptions

Caesar’s Comet

An extraordinary naked-eye comet seen in 44BC and celebrated as Julius Caesar’s ‘comet of Augustus.’ Extremely bright and visible in daylight, it was politically significant and widely recorded, suggesting a long-period visitor with a dramatic, conspicuous tail across the Mediterranean sky.

Halley’s Comet

Halley’s Comet in 1066 blazed over Europe and is famously depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry. Easily visible to the unaided eye, it influenced medieval observers and rulers. A 76-year periodic comet, its appearances provide key historical anchors for orbital astronomy.

Great Comet of 1577

Observed across Europe and studied by Tycho Brahe, this comet helped show that comets travel beyond the Moon. Bright and widely seen, its path and lack of measurable parallax were crucial to early modern astronomy and public fascination with celestial events.

Great Comet of 1618

One of three bright comets seen in 1618, this apparition drew intense observation and debate about cometary nature. Naked-eye bright with long tails, it was recorded across Europe and Asia and influenced scientific and astrological discourse of the era.

Great Comet of 1680 (Kirch)

The Great Comet of 1680, discovered by Gottfried Kirch, showed a long, striking tail and was visible in both hemispheres. Its path close to the Sun and dramatic display captivated observers and contributed to orbital calculations in the late 17th century.

Great Comet of 1744 (C/1743 X1)

This comet produced an unforgettable multi-tailed display visible even in daylight for some observers. Spectacular tails and intense brightness made 1744 a cultural and scientific sensation across Europe, inspiring sketches, reports, and astronomical study for months.

Great Comet of 1811 (C/1811 F1)

Visible for many months, the 1811 comet impressed contemporaries with its bright nucleus and long tail. It was widely recorded across Europe and the Americas and became associated with significant historical events—an enduring example of a long-lasting naked-eye comet.

Great Comet of 1843 (C/1843 D1)

A dramatic sungrazing comet that developed an immense, curved tail and became extremely bright near perihelion. Visible in daylight near the Sun, its spectacular appearance and near-sun path marked it as one of the 19th century’s most notable comets.

Donati’s Comet

Donati’s Comet of 1858 produced a graceful, luminous tail and became a global artistic and scientific subject. Easily seen with the naked eye in the evening sky, it inspired paintings and widespread public interest while advancing observational comet studies.

Great Comet of 1861 (C/1861 J1)

A bright, conspicuous comet that developed a long tail and was widely observed in both hemispheres. Its strong visibility to the naked eye and dramatic tail structure made it an important object for 19th-century astronomers and the watching public.

Great Comet of 1882 (C/1882 R1)

A spectacular Kreutz sungrazer that fragmented and produced intense brightness near the Sun. Its multiple tails and daylight visibility impressed global observers and helped define the extreme behaviour of sungrazing comet fragments.

Great Comet of 1910 (Halley)

Halley’s 1910 apparition was famous for bright visibility and public anxiety when Earth passed through its tail. Well recorded worldwide, it offered excellent photographic and spectroscopic opportunities and reinforced Halley’s central role in historical comet studies.

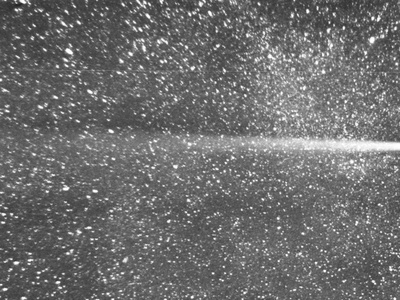

Ikeya–Seki

A spectacular sungrazing comet in 1965 that became extraordinarily bright near perihelion, briefly outshining daytime sky near the Sun. It split into fragments and produced intense tails, making it one of the 20th century’s most dramatic naked-eye comets and a keystone sungrazer study.

Bennett (C/1969 Y1)

Comet Bennett brightened into naked-eye visibility in 1970, showing a fine tail and pleasant evening appearance. Well-observed by amateur and professional astronomers, it became a popular and accessible example of a classical long-period comet.

West (C/1975 V1)

Comet West delivered a spectacular display after perihelion in 1976 with a bright head and long, structured tail. Its sudden flaring and excellent southern-hemisphere visibility made it a modern “great” comet widely seen and photographed by the public.

Arend–Roland

Arend–Roland brightened to naked-eye visibility in 1957, producing a distinct tail and steady public interest. Observed across mid-latitudes, its predictable track and clear display made it a notable mid-20th-century comet for skywatchers and observatories.

Hyakutake

Hyakutake passed unusually close to Earth in 1996, producing vivid, long ion tails and spectacular naked-eye views. Its proximity made fine tail structure visible to the unaided eye and spurred intensive scientific observations and public enthusiasm worldwide.

Hale-Bopp

Hale–Bopp was an exceptionally bright, long-lasting comet visible to the naked eye for months in 1996–1997. Its strong coma and twin tails made it a cultural touchstone, and its long orbital period (roughly 2,533 years) highlighted its rarity and scientific value.

McNaught (C/2006 P1)

Comet McNaught became extremely bright in 2007, visible in daylight near the Sun and producing a vast, stiff tail. Observers across the southern hemisphere enjoyed one of the brightest comets in recent decades, notable for its intense perihelion brightness.

Lovejoy (C/2011 W3)

A resilient sungrazing comet that survived perihelion in 2011 and produced a spectacular post-perihelion tail visible to the naked eye. Its dramatic survival and vivid display provided both amateur enjoyment and useful data on sungrazer behaviour.

NEOWISE (C/2020 F3)

NEOWISE became the brightest naked-eye comet of 2020, offering a broad fan-shaped tail visible across both hemispheres in July. Easily spotted without optics, it reintroduced many city-dwellers to comet-watching and inspired renewed public interest in transient sky events.

Great Comet of 1844 (C/1844 Y2)

This mid-19th century comet produced a bright head and long, elegant tail observable across Europe and beyond. Its prominence in sky reports and drawings of the era made it a memorable naked-eye object and important data point for historical comet catalogs.

Great Comet of 1680 (Second listing note)

The 1680 apparition was a lengthy, bright spectacle with a long tail visible to many observers; its extended visibility and timing just after the invention of telescopes made it a formative event in observational comet history and celestial mapping.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.