In 2006 astronomers announced a startling find: PSR J1748−2446ad, a pulsar in the globular cluster Terzan 5, was spinning 716 times per second (period 1.396 ms). That discovery immediately put extreme rotation on the map and showed how strange and energetic the cosmos can be.

Rotation in space spans an enormous range — from tiny meteoroids that can spin in fractions of a second to millisecond pulsars and near-maximal black-hole spins. These differences matter because spin affects structure, emission, stability, and even how objects interact with spacecraft and atmospheres.

Astronomers measure spins with a few reliable techniques: pulsation timing for pulsars, X-ray and optical pulsations for compact objects, spectral line broadening for stars, and photometric light curves or radar for small bodies.

This countdown groups examples into three categories — compact remnants; stars, brown dwarfs, and disks; and small bodies plus human-made hardware — and explains why each type can reach such high spin rates.

Compact stellar remnants: neutron stars, pulsars, white dwarfs, and black holes

When a massive star collapses, conservation of angular momentum can spin the leftover core up to incredible rates, and subsequent accretion from a companion can push a compact object to millisecond periods.

Different classes are measured with different techniques: radio timing and pulse arrival for pulsars, X-ray pulsations for accreting systems, and optical or X-ray timing for fast white dwarfs.

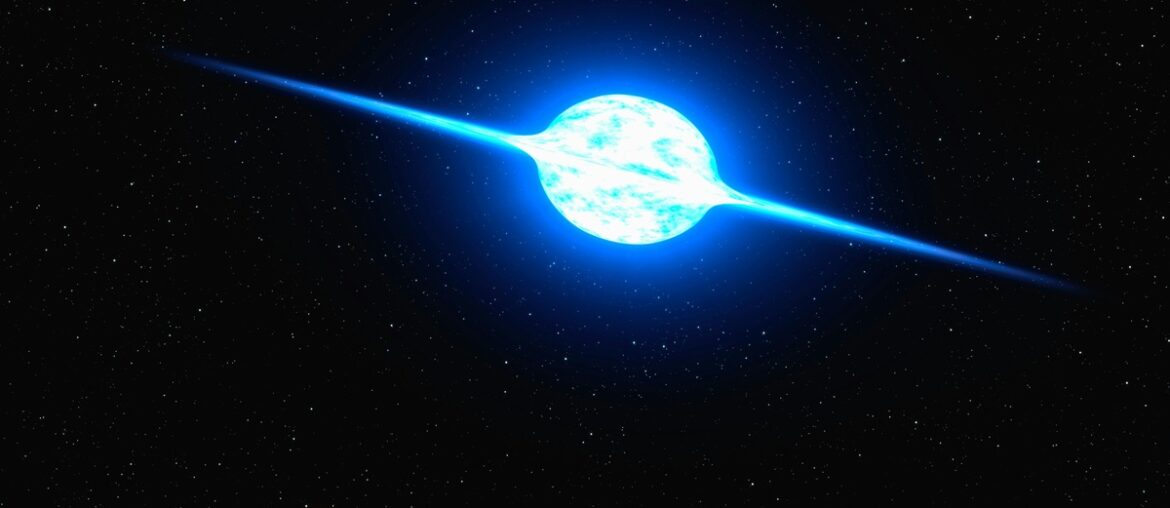

1. Millisecond pulsar PSR J1748−2446ad — 716 Hz (period 1.396 ms)

PSR J1748−2446ad is the fastest firmly measured pulsar, spinning 716 times per second (period 1.396 milliseconds).

It was discovered in 2006 in the dense globular cluster Terzan 5 and its spin was measured via precise radio timing of pulse arrivals.

Such rapid rotation is a hallmark of accretion-driven spin-up and provides tight constraints on the neutron-star equation of state because an object that spins this fast must be compact and structurally robust.

2. Candidate XTE J1739−285 — claimed burst oscillation at 1122 Hz (unconfirmed)

XTE J1739−285 produced a controversial report in the mid-2000s of a burst oscillation at 1122 Hz (about a 0.89 ms period), which would make it far faster than any confirmed pulsar.

The detection remains debated because burst signals are transient and often low signal-to-noise, making it hard to rule out statistical fluctuation or instrumental effects.

If such a spin were confirmed, it would strongly constrain neutron-star radii and the stiffness of dense nuclear matter, challenging some proposed models.

3. Fast white dwarf RX J0648.0−4418 — period 13.2 seconds

RX J0648.0−4418, the compact companion to HD 49798, spins with a period of 13.2 seconds, making it one of the fastest known white dwarfs.

XMM-Newton X-ray pulsation measurements and mass estimates around 1.28 solar masses indicate a massive, rapidly rotating white dwarf in a close binary system.

Because white dwarfs are much larger than neutron stars, a 13.2 s period implies substantial angular momentum and has implications for accretion evolution and potential pathways toward thermonuclear (type Ia) outcomes.

4. AE Aquarii — a rapidly spinning 33.08-second white dwarf

The white dwarf in AE Aquarii rotates every 33.08 seconds and behaves like a magnetic propeller that expels much of the incoming material instead of accreting it efficiently.

Observers see strong pulsed optical and X-ray emission and non-thermal signatures that reveal magnetospheric interaction and rapid angular-momentum loss.

AE Aquarii is a useful nearby laboratory for studying how magnetic fields and rotation influence accretion and outflow physics.

5. Rapid black-hole spins (example: GRS 1915+105 with a* ≈ 0.98–0.99)

Black holes are characterized by a dimensionless spin parameter a* rather than a simple rotation frequency; values close to 1 indicate near-maximal spin.

GRS 1915+105 is a well-studied example with measured spin a* ≈ 0.98–0.99 from X-ray continuum-fitting and reflection modeling, implying the innermost stable circular orbit lies very close to the event horizon.

High black-hole spin increases radiative efficiency, alters inner-disk dynamics, and is linked to powerful relativistic jets, though comparing a* to pulsar Hz is not a direct apples-to-apples comparison.

Stars, brown dwarfs, and accretion disks: rapid rotation across stellar types

Stars inherit angular momentum from their birth clouds, and interactions in binaries or during formation can spin them up toward breakup speeds.

Astronomers measure stellar rotation with spectral line broadening and photometric modulation caused by spots or brightness asymmetries; disks are probed via timing of inner-disk signatures like kHz QPOs.

6. O-type star VFTS 102 — equatorial velocity ~600 km/s

VFTS 102, identified in the VLT-FLAMES Tarantula Survey (reported 2011), is among the fastest rotating massive stars known, with an equatorial velocity of order 600 km/s.

Rotation this fast approaches the breakup limit, promoting equatorial mass loss, enhanced mixing, and possible disk formation around the star.

Rapidly spinning massive stars are candidate progenitors for some long gamma-ray bursts in models that require high angular momentum at collapse.

7. Fast-rotating brown dwarfs — periods down to ~1–2 hours

Brown dwarfs, with radii similar to Jupiter but larger masses, often retain substantial spin and several have photometrically measured rotation periods as short as one to two hours.

Surveys of L and T dwarfs using ground-based telescopes and Spitzer have reported sub-2-hour rotators, inferred from periodic brightness modulations caused by patchy clouds or spots.

Those fast rotators inform models of interior structure, angular-momentum evolution, and atmospheric dynamics under rapid Coriolis forces.

8. Inner accretion-disk orbital frequencies — kilohertz regimes (300–1,200+ Hz)

Material orbiting close to neutron stars or black holes reaches orbital frequencies in the kilohertz range rather than rotating like a solid body.

Low-mass X-ray binaries show kHz quasi-periodic oscillations (QPOs) with frequencies from roughly 300 to over 1,000 Hz, and some reports push toward 1,200–1,300 Hz for short-lived signals.

These rapid orbital motions probe strong-gravity regions, constrain compact-object masses and radii, and help us understand how the innermost disk couples to jet formation.

Small bodies and human-made objects: asteroids, meteoroids, and spinning hardware

For small bodies the balance between self-gravity and material strength sets spin limits: rubble piles can be shredded at modest rotation rates, while coherent rocks and metal fragments can spin much faster.

The YORP effect (torques from sunlight) and collisions are key drivers of spin changes for asteroids; radar and light-curve monitoring reveal their rotation states.

9. Asteroid 2008 HJ — rotation period ~42.7 seconds (fastest known natural solar-system spinner)

Asteroid 2008 HJ was observed to complete a rotation in about 42.7 seconds, one of the shortest measured rotation periods for a natural solar-system object.

Discovered in 2008, its rapid spin was determined from optical light-curve analysis that revealed a repeating brightness pattern on that timescale.

Such fast rotation implies internal cohesion rather than a loose rubble pile and matters for planetary-defense scenarios and design of rendezvous or sample-return missions.

10. Meteoroids and tiny fragments — extremely high spin rates (seconds to sub-seconds)

Meter-to-centimeter-scale meteoroids and fragments can reach very high spin rates, with periods down to fractions of a second, driven by impacts and thermal torques similar to YORP.

Detection is challenging; radar echoes, rapid light-curve flicker, and in-atmosphere fragmentation patterns provide indirect evidence that tiny pieces often spin at hundreds to thousands of rotations per minute.

Rapid spin affects how objects break up during atmospheric entry and changes the risk profile for satellites struck by small, fast-rotating debris.

11. Human-made objects in orbit — tumbling rocket stages and fragments (tens to thousands of rpm)

Released hardware, spent upper stages, and fragmentation debris commonly tumble; small pieces and paint flecks can have effective spin rates ranging from tens to thousands of revolutions per minute.

Some satellites are spin-stabilized intentionally (for example, certain CubeSats), while many upper stages end life tumbling, complicating tracking and remediation efforts.

Radars and optical tracking campaigns measure rotation rates and help inform space situational awareness, collision avoidance, and debris mitigation planning.

Summary

- Spin in the universe spans enormous scales — from sub-second fragments to millisecond pulsars (e.g., PSR J1748−2446ad at 716 Hz) and near-maximal black-hole spins.

- Conservation of angular momentum during collapse and accretion-driven spin-up explain compact-object extremes, while YORP and collisions drive spins among small bodies.

- Measurement methods vary: radio timing and X-ray pulsations for compact remnants, spectral line broadening and photometric monitoring for stars and brown dwarfs, and light curves or radar for asteroids and debris.

- Practical implications range from testing dense-matter physics and general relativity to engineering concerns for spacecraft, planetary defense, and debris mitigation — and even everyday timing applications like pulsar-based clocks.

- New surveys and instruments will likely turn up still more extreme examples among the fastest spinning objects in space, so keep an eye on timing studies and high-cadence surveys.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.