In the late 1800s and early 1900s, prominent astronomers mapped “canals” on Mars and serious scientific journals debated whether the Red Planet harbored intelligent life. That episode is a reminder: bold claims about other worlds can capture the public imagination and steer decades of research.

Mistaken ideas about space matter because they shaped missions, funding priorities, and what people expected when probes finally arrived. A wrong turn can be embarrassing, sure. But it also exposes gaps, forces better measurements, and motivates new methods.

Here are six notable wrong space theories, each described in plain terms: what was proposed, when it was popular, how it was overturned, and the concrete lessons learned.

1. Outdated models of planetary motion

For centuries, astronomers used Earth-centered geometric schemes to predict planetary positions. Those models were efforts to force complex sky paths into a fixed framework, limited by the precision of naked-eye and early instrument observations.

They mattered. Calendars, navigation, and astrology relied on them, so the models persisted until new data and simpler mathematics displaced them. The transition to heliocentrism and Kepler’s laws shows how better observations and theory reduce complexity and increase predictive power.

1. Geocentrism and Ptolemy’s epicycles

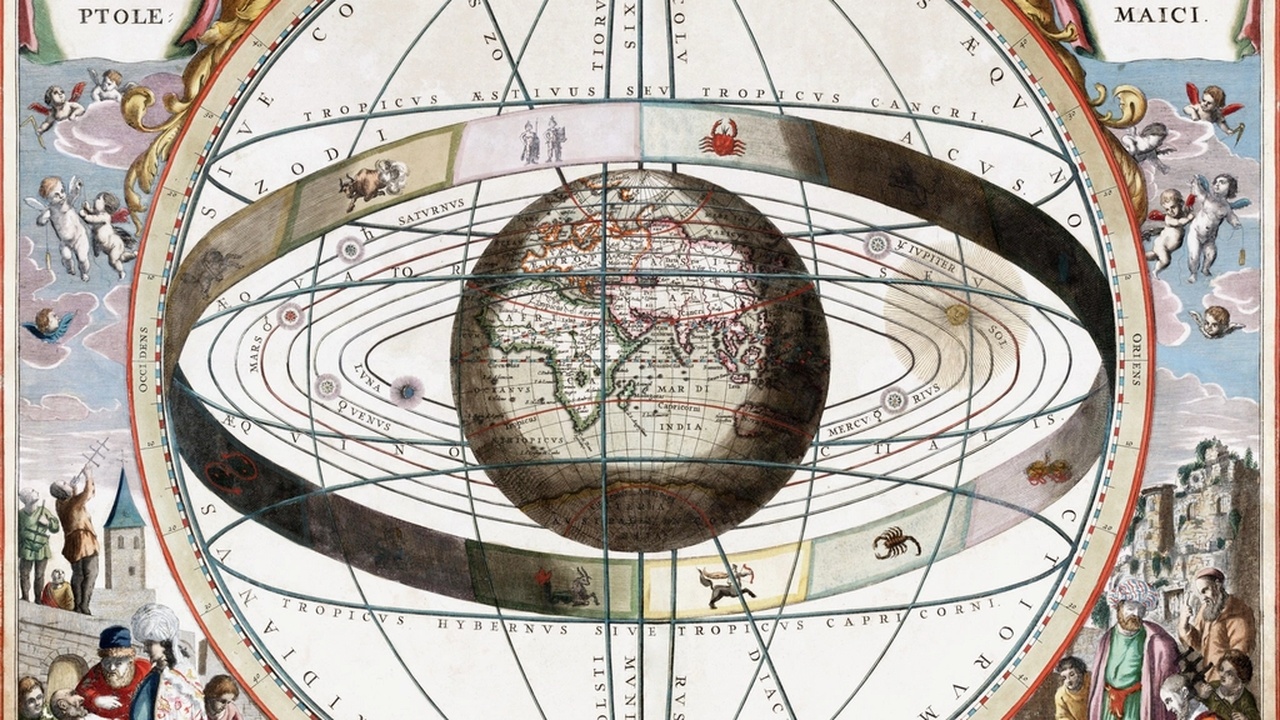

For roughly 1,400 years the Ptolemaic geocentric model dominated astronomy. Claudius Ptolemy’s Almagest (2nd century CE) described planets moving on circles (deferents) with smaller circles (epicycles) riding atop them.

Epicycles let the model match observed positions, including the retrograde motion of Mars, when a planet appears to move backward for a while. That odd loop was handled by layered circles rather than a changing viewpoint.

Copernicus published De revolutionibus in 1543 and shifted the frame to the Sun. Kepler’s work — Astronomia Nova (1609) and Harmonices Mundi (1619) — replaced circular epicycles with simple ellipses. Elliptical orbits made retrograde motion a natural consequence of relative motion, removing the need for many ad hoc corrections.

Takeaway: A model that fits data by piling on complications is often a sign to look for a simpler underlying law.

2. The long life of epicycles before Kepler

Instead of abandoning the whole framework, successive astronomers added more epicycles as observations improved. Medieval and Renaissance tables sometimes used dozens of nested epicycles to shave residual errors down.

Those ad hoc fixes prolonged the geocentric picture because the models still made usable predictions for calendars and navigation. But the growing complexity was an epistemic red flag: the theory was under stress.

When heliocentrism and Kepler’s laws arrived, the same data could be described with far fewer assumptions and far better predictive accuracy. The episode highlights that increasing complexity can mask the need for a new framework.

2. Misread planetary observations and Martian myths

Low-resolution telescopes, grainy photographic plates, and wishful thinking made fertile ground for durable but incorrect claims about Mars and Venus. Optical artifacts and cultural expectations turned ambiguous marks into grand narratives.

Instrumental limits can create false patterns. Cultural biases then amplify those patterns until direct spacecraft data provide the deciding test. The next two sections show how that played out for Mars and Venus.

3. The Martian “canals” and misplaced optimism

In 1877 Giovanni Schiaparelli described linear features on Mars as “canali.” English readers translated that as artificial “canals,” and Percival Lowell popularized the idea from about 1894 into the 1910s with detailed sketches from Lowell Observatory.

Observers later realized the lines were most likely optical illusions and pattern-seeing under poor seeing conditions. Atmospheric turbulence and the limits of eyepiece resolution create spurious linear features.

The final disproof came from spacecraft. On July 14, 1965 Mariner 4 returned 21 low-resolution images showing a heavily cratered surface far more Moon-like than canal-rich. The myths, however, did something useful: they drove public interest and funding that eventually sent probes to Mars.

4. Venus as a temperate, watery world (and why radar proved otherwise)

In the 19th and early 20th centuries many scientists and writers imagined Venus hiding oceans and lush vegetation beneath a permanent cloud deck. The thick clouds made direct telescopic study impossible, inviting optimistic speculation.

Mid-20th-century radio and radar observations in the 1960s began to probe the surface. Those remote-sensing experiments suggested extreme conditions, a result later confirmed by in-situ probes.

Soviet Venera landers began arriving in the late 1960s, and Venera 7 provided the first successful surface data in 1970. Surface temperature measurements are roughly 735 K (462°C) and surface pressure about 92 bar, with clouds rich in sulfuric acid. The once-appealing idea of a temperate Venus was decisively overturned.

3. Cosmology ideas that failed empirical tests

Theory-driven cosmology invites bold alternatives. Two influential wrong space theories rose and fell as better observations reached cosmological scales: one posited a time-invariant universe, the other tried to avoid expansion by draining photon energy.

Both showed how decisive new datasets can be when a hypothesis fails multiple independent tests.

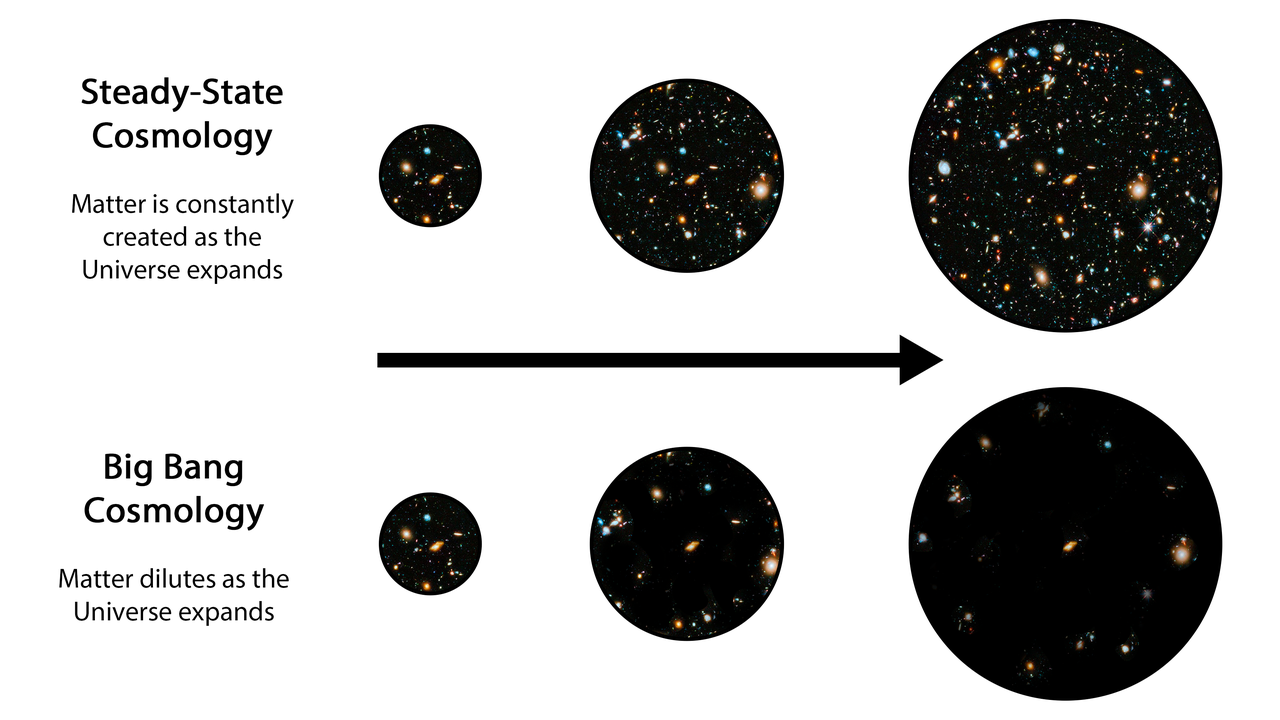

5. The Steady State universe

In 1948 Fred Hoyle, Hermann Bondi, and Thomas Gold proposed the Steady State model: the universe looks essentially the same at all times because new matter is continuously created to keep the average density constant.

The idea appealed to those who wanted to avoid a cosmic beginning. It was elegant in its own way, but it made concrete observational predictions about the distribution and age of distant objects.

In 1965 Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson detected the cosmic microwave background at roughly 2.7 K. That relic radiation fits naturally with a hot Big Bang and not with a time-invariant universe. Counts of radio galaxies and quasars show clear evolution with redshift, and later missions (COBE in 1989–1993, then WMAP and Planck) measured the CMB’s spectrum and anisotropies with precision. Those results effectively falsified the Steady State picture.

Lesson: Ambitious cosmological models must face data from many independent probes, and precision measurements can settle debates once murky at large scales.

6. “Tired light” and other alternatives to expansion

Fritz Zwicky proposed “tired light” in 1929 as a non-expansion explanation for the redshift: photons lose energy over vast distances and redden, rather than space itself stretching.

That mechanism seemed to offer a way around cosmic expansion, but it fails on several observational counts. Time-dilation observed in Type Ia supernova light curves (measured clearly in the 1990s) matches the stretching expected from expansion, not an energy-loss process.

Spectral tests, surface brightness relations, and the cosmic microwave background further rule out simple tired-light scenarios. The broader point: an idea that sounds plausible must survive multiple, independent empirical checks across observables.

Summary

- Scientific mistakes often point the way forward: failed models highlight where observations are lacking and spur better instruments and missions.

- Better data are decisive. Mariner 4’s 21 Mars images (1965), Venera landers beginning in 1967 with Venera 7’s 1970 surface data, and Penzias & Wilson’s 1965 CMB detection changed debates that had lasted decades.

- Cultural appetite and public fascination matter. Myths like Martian canals attracted funding and attention that ultimately sent probes to test the claims.

- Good science tolerates being wrong. Hypotheses get refined or discarded as methods improve, and that iterative process is how our picture of the cosmos becomes more reliable.

- Keep an eye on upcoming missions and data. New telescopes and sample-return missions will challenge current big ideas and, yes, probably overturn a few more cherished notions.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.