When Voyager 1 flew past Jupiter in March 1979 it photographed towering plumes and rivers of molten rock on Io — the first time active volcanism was seen on a world beyond Earth. The images of columns of gas and ash rising hundreds of kilometers and orange-black lava fields left a lasting impression: Io is wild, bright, and utterly unlike the icy moons nearby.

Io earns the title “deadliest moon” not because of a single hazard but because multiple extreme processes — intense volcanism, crushing tidal forces, corrosive chemistry and brutal radiation — combine to make it one of the most hostile places in the solar system. That cluster of dangers is exactly why io is deadly for explorers, and why scientists are fascinated: it’s a natural laboratory for high-temperature volcanism, tidal physics, and magnetospheric chemistry. Below are ten concrete reasons grouped into three categories: Volcanism and Surface Hazards; Environmental Extremes from Jupiter’s Influence; and Challenges for Exploration and Habitability.

Volcanism and Surface Hazards

1. Extreme volcanic activity — hundreds of active volcanoes

Io hosts hundreds of active volcanoes. Voyager 1’s 1979 flyby revealed dramatic plumes, and later infrared mapping by the Galileo mission and ground-based telescopes confirmed dozens to hundreds of active vents across the surface (NASA/JPL).

Conservative tallies put the number of persistent or episodically active vents in the order of 100–400, with large features such as Loki Patera standing out as some of the most powerful volcanic sources in the solar system. Frequent eruptions continually reshape terrain, producing fresh lava fields and unpredictable hazards for any lander or rover.

Studying those eruptions gives researchers a rare look at high-flux magma systems and helps test ideas about early-Earth volcanism — but for hardware and humans the frequent activity means potential burial by flows, ejecta impacts, and a landscape that can change between mission planning and arrival.

2. Sulfur and sulfur dioxide coatings — corrosive, colorful, and hazardous

Io’s surface is dominated by sulfur and sulfur dioxide frost rather than water ice. Plume deposits produce the moon’s striking yellows, reds and blacks as different sulfur allotropes and SO2 frost settle onto plains (Galileo observations; NASA).

Those sulfur compounds are chemically active and can be corrosive to metals and polymers used in spacecraft. Instruments and seals can foul quickly if coated by plume fallout, and chemical weathering complicates any plans for in-situ resource use or long-term deployment of sensitive equipment.

Persistent sulfur rain and patchy frost also change surface reflectivity and thermal properties, making remote sensing calibration and surface-landing predictions more difficult than on inert, rocky bodies.

3. High-temperature silicate lava — hotspots hotter than most solar-system examples

Some Io lavas reach temperatures comparable to or higher than typical terrestrial basalt flows. Infrared work from Galileo and telescopic monitoring suggest lava temperatures up to roughly 1,600 K (about 1,300 °C) at active vents (NASA/JPL).

Extremely hot lava produces fast-moving flows and long, thin lava fields that can travel tens to hundreds of kilometers. For a landing site, nearby hotspots are a direct thermal and impact hazard; for instruments, radiant heat and molten spatter are immediate threats.

From a scientific standpoint, those temperatures provide analogs for early, high-temperature volcanism on Earth and give unique constraints on mantle composition and melt dynamics under strong tidal heating.

Environmental Extremes from Jupiter’s Influence

4. Intense tidal heating — internal molten engines

Tidal flexing from Jupiter, amplified by the 1:2:4 Laplace resonance with Europa and Ganymede, pumps enormous heat into Io’s interior. That orbital resonance maintains a small but persistent eccentricity, driving continual mechanical deformation and heating.

Measured surface heat flow on Io is orders of magnitude higher than Earth’s global average geothermal flux; estimates put Io’s average at a few watts per square meter compared with Earth’s ~0.08 W/m² (Galileo-era studies; NASA). That steady input of energy keeps large volumes of rock molten and sustains relentless volcanism.

Tidal heating is also scientifically important because it shows how external gravity can be an internal heat engine, a process relevant for other moons and exoplanets — but for explorers it means an actively changing interior and surface regime.

5. Brutal radiation from Jupiter’s magnetosphere

Io orbits well inside Jupiter’s powerful radiation belts and is continually bombarded by energetic electrons and ions trapped in the planet’s magnetosphere. Radiation levels near Io are hundreds to thousands of times higher than typical Earth background values (JPL/NASA assessments).

Those particle fluxes would disable electronics and be lethal to unshielded humans in minutes to hours. Even hardened spacecraft experience rapid degradation of detectors, solar arrays, and circuitry; Galileo’s instruments and mission planning had to account for—and were limited by—that radiation environment.

Mission design for any probe near Io demands heavy shielding, redundant systems, and brief exposure times, and planners for missions focused on other Jovian moons generally avoid close Io passes because of this hazard.

6. The Io plasma torus — a ring of charged, corrosive material

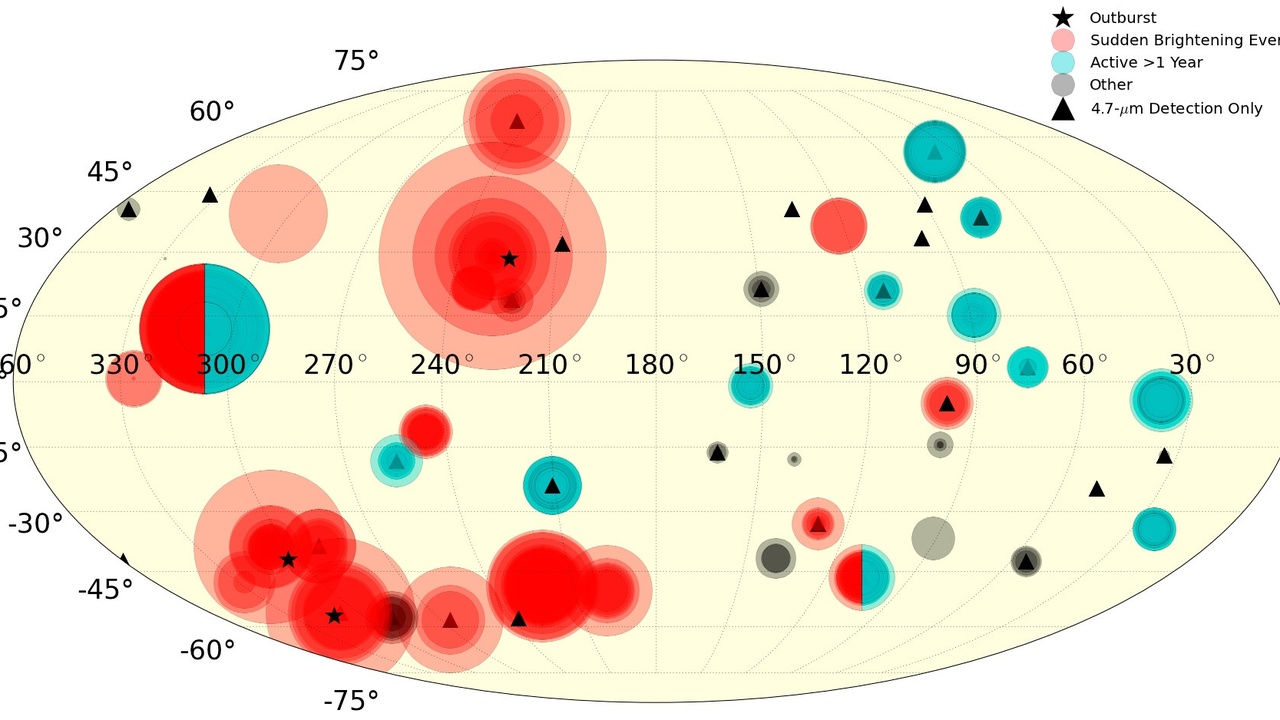

Volcanic gases escaping Io become ionized and form the Io plasma torus: a doughnut-shaped ring of sulfur and oxygen ions encircling Jupiter. That torus glows in ultraviolet and radio wavelengths and is a direct product of Io’s volcanic output (observed by Galileo and Hubble).

Order-of-magnitude estimates suggest Io supplies material to the torus at rates on the order of 1 ton per second. That mass input creates a dense, charged-particle environment that alters spacecraft charging, corrodes surfaces over time, and complicates communications and operations.

From a research perspective, the torus is a unique laboratory for magnetospheric physics; from an engineering perspective, it’s a persistent, space-environment hazard tied directly to Io’s volcanism.

7. Volcanic plumes and ejecta — falling debris and unpredictable resurfacing

Volcanic plumes on Io can loft sulfur and silicate particles hundreds of kilometers above the surface; plume heights up to roughly 300 km have been observed (Voyager, Galileo, and later monitoring).

Ejecta falls back as fine particulates and larger fragments, which can coat, sandblast, or bury equipment. Persistent plumes like Prometheus leave trailing sulfurous deposits, while explosive sources such as Pele produce wide-ranging fallout that rapidly alters local composition and topography.

For landers, the unpredictable timing and reach of plumes make site selection risky: a safe-looking plain today can be buried or chemically altered after a nearby eruption.

Challenges for Exploration and Habitability

8. A tenuous atmosphere — only trace SO2, not breathable and not protective

Io’s atmosphere is extremely thin and transient, dominated by sulfur dioxide with surface pressures measured in the nanobar range — roughly 10⁻⁹ to 10⁻⁸ bar, changing with local temperature and volcanic activity (ground-based spectroscopy and spacecraft flybys).

That atmosphere offers no breathable air and essentially no shielding from radiation or micrometeoroids. Local variations near active plumes can be large, so a lander could encounter near-vacuum conditions one minute and dense plume gas the next.

Practically, habitats and suits must be fully sealed and life-support supplies brought in; there are no atmospheric resources suitable for direct use without complex processing.

9. Scarcity of water and volatiles — a dry, sulfur-rich world

Unlike Europa or Ganymede, Io lacks substantial surface water ice or a confirmed subsurface ocean. Its composition is dominated by silicates and sulfur compounds, making it a dry world compared with its Galilean neighbors.

That scarcity has direct consequences: water for life support, fuel production, and radiation shielding would have to be delivered from elsewhere or manufactured at great expense. Mission mass and complexity rise quickly when you can’t rely on local volatiles.

Comparing moons is instructive: Europa’s subsurface ocean presents resource and astrobiology potential, whereas Io is focused on active geology and magnetospheric interaction rather than habitability.

10. Engineering hurdles — corrosive deposits, thermal extremes, and navigation risks

Io combines multiple engineering headaches into one package. Corrosive sulfur deposits chemically attack spacecraft materials, while charged-particle bombardment causes surface charging and electrical damage.

Thermal extremes are extreme indeed: background surface temperatures on SO2-frosted plains can be near ~110 K, yet local lava and vents exceed 1,000 °C. That range demands materials and thermal control systems that handle both cryogenic cold and intense localized heat.

Navigation and mobility are also harder here. Rapid resurfacing, hidden lava tubes, and unstable deposits increase the risk of a lander getting trapped or damaged. The practical response is heavy shielding, heat-tolerant components, redundant systems, and very short, carefully planned surface campaigns.

Summary

- Io’s hazards multiply: relentless volcanism, tidal heating from Jupiter, corrosive sulfur chemistry and intense magnetospheric radiation combine to make exploration uniquely difficult (Voyager and Galileo revealed many of these features).

- Despite the danger, Io offers high scientific payoff — from extreme-temperature volcanism to active magnetosphere-plasma interactions — knowledge that informs planetary science and exoplanet studies.

- Practical exploration must prioritize heavy radiation shielding, corrosion-resistant materials, thermal protections, and short-duration surface operations; remote sensing and flybys remain the lower-risk first steps.

- For mission planners weighing targets across the Jovian system, the reasons Io is hazardous are also the reasons to study it: a hard testbed for engineering and a window into processes that shape many worlds.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.