When Galileo Galilei trained a small spyglass on Jupiter in 1610 he found four moons; one of them, Ganymede, would later be measured at a surprising 5,268 km across—larger than the planet Mercury. That simple observation changed how we think about moons and planets. If you’re wondering why Ganymede is interesting, consider its planetary scale, a hidden ocean, a native magnetic field, and a surface that reads like a geological record. Those factors make Ganymede a prime target for scientific discovery, astrobiology, and upcoming missions. ESA’s JUICE and NASA’s complementary studies promise to turn decades of hints into detailed data, so now is the moment to pay attention.

Size and Planetary Importance

Ganymede’s sheer size changes how scientists treat it: not merely an icy satellite but a world with planet-like structure and processes. Its dimensions and mass make it a high-priority target for long-term study and for missions designed to probe internal layers, magnetic fields, and surface history.

1. Largest Moon in the Solar System — bigger than Mercury

Ganymede is the largest moon in the Solar System, measuring about 5,268 km in diameter—compare that to Mercury’s 4,880 km and Earth’s Moon at roughly 3,474 km. Size matters: a larger body retains more internal heat and can undergo differentiation into layers rather than remaining a homogeneous icy ball.

That differentiation—separating metal, rock, and ice—gives Ganymede many planet-like qualities. Galileo’s 1610 discovery of the Galilean moons began the story, and spacecraft investigations in the 1990s, especially the Galileo orbiter, provided the first detailed flyby data that showed Ganymede deserves study on its own terms. NASA and ESA routinely describe Ganymede as a world with planetary characteristics rather than a simple satellite.

2. Planetary-like interior and composition

Ganymede isn’t just big; its internal structure appears layered. Gravity and magnetic data from NASA’s Galileo mission point to a metallic core surrounded by a silicate mantle and thick ice layers. The moon’s average density implies a significant rock-to-ice ratio rather than pure ice.

That differentiation matters because it enables processes more typical of small planets—core convection, long-lived heat sources, and a history of internal evolution. Comparing Ganymede’s mixed rock-ice composition to Mercury’s iron-rich interior highlights why a larger radius doesn’t automatically mean similar composition. Studying Ganymede refines models for icy worlds and for moons we may find orbiting exoplanets.

Hidden Ocean and Habitability Potential

Subsurface oceans are at the top of astrobiology’s shopping list. Liquids beneath ice provide stable environments, potential chemical gradients, and — crucially — a place where life as we know it could exist. Ganymede ticks many of the boxes that make ocean worlds exciting.

3. A deep subsurface ocean — one of the largest in the Solar System

Multiple lines of evidence point to a subsurface ocean on Ganymede. Gravity measurements, surface geology, and magnetic signatures measured during Galileo flybys indicate a conductive layer beneath the ice. Models suggest that ocean could be tens of kilometers thick in places.

That’s significant: an ocean this deep may hold a volume of water comparable to or exceeding Earth’s oceans, cautiously speaking. Liquid water plus chemical gradients—driven by interactions with the rocky interior or tidal heating—creates the basic ingredients for habitability. Instruments planned on ESA’s JUICE, such as ice-penetrating radar and magnetometers, are built specifically to test these hypotheses.

4. An intrinsic magnetic field — rare among moons

Ganymede is the only moon known to generate its own intrinsic magnetic field. Galileo’s magnetometer detected a persistent field in the 1990s, and that field carves out a miniature magnetosphere inside Jupiter’s vast magnetic environment.

The implications are practical and scientific. A native field can partially shield surface regions from charged particles, alter sputtering patterns, and change surface chemistry. It also provides a probe of the interior: a dynamo implies a conductive, convecting core or a global, salty layer that responds to magnetic forcing. JUICE will map this magnetic environment in far greater detail and quantify how Ganymede’s field interacts with Jupiter’s.

Surface, Tectonics and the Jovian Context

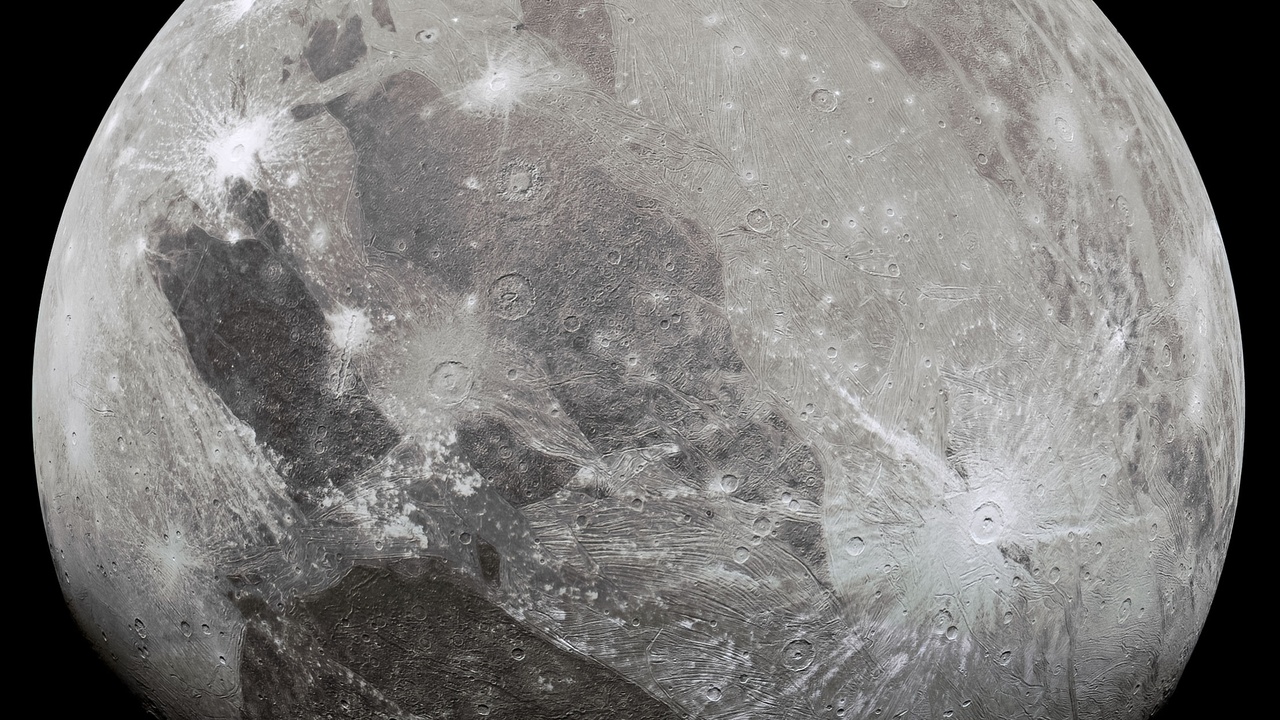

Ganymede’s surface contrasts are dramatic: bright, grooved terrain sits beside older, darker plains peppered with craters. Those differences record shifts in internal stress, surface renewal, and external forcing from Jupiter—making the surface a time capsule of the Jovian system.

5. A complex surface — grooves, faults, and ice tectonics

Voyager and Galileo images revealed long linear grooves, ridges, and banded terrains that stand in stark contrast to heavily cratered dark areas. Places like Uruk Sulcus show networks of parallel ridges and troughs that suggest large-scale tectonic deformation of an ice shell.

These grooves probably formed when the ice shell fractured and moved, perhaps aided by cryovolcanic resurfacing or diapiric upwelling. Studying them teaches us how ice behaves under stress, informs models for other icy moons, and helps planners choose landing sites or orbital passes for instruments that can read the crust’s structure.

6. A recorder of the Jovian system’s history

Ganymede’s surface and orbit preserve a record of the dynamical history of Jupiter’s satellites. It completes an orbit roughly every 7.15 Earth days and participates in the 1:2:4 Laplace resonance with Europa and Io, a configuration that shapes tidal heating and orbital evolution.

That resonance and the moon’s interactions with Jupiter’s magnetosphere leave measurable imprints: heat distribution, tectonic strain, and surface alteration from charged particles. By decoding Ganymede’s geological and orbital record, scientists reconstruct past migrations, tidal histories, and environmental conditions that affected the entire Jovian system. Those reconstructions, in turn, guide theories of moon formation and evolution around other giant planets.

Summary

- Ganymede’s planetary scale—with a diameter of about 5,268 km—recasts it as a world rather than a mere satellite.

- The moon’s differentiated interior and vast subsurface ocean make it a key target for studies of internal dynamics and habitability.

- Its intrinsic magnetic field and interaction with Jupiter’s magnetosphere offer a rare laboratory for magnetospheric physics.

- The surface preserves tectonic and collisional records—grooved terrains and cratered plains—that reveal the Jovian system’s past.

- Upcoming missions will change our view: ESA’s JUICE launched in 2023, arrives at Jupiter in 2031, and will enter orbit around Ganymede in 2034, promising detailed maps of ice, ocean, and field.

Three takeaways: Ganymede combines scale, water, and magnetism in a way few other moons do; it preserves both internal and system-wide histories; and JUICE (with complementary observations) will soon turn speculation into measurements. That’s why Ganymede will be central to planetary science for years to come.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.