In 1995 astronomers announced 51 Pegasi b, the first planet found orbiting a Sun-like star — and with it came the question: what is its atmosphere like? That discovery shifted the field from counting planets to asking what those worlds are made of and how they formed.

Spectroscopy became the next frontier: by spreading a planet’s light into a spectrum we can read chemical fingerprints — water vapor, sodium, carbon dioxide and more — in a way roughly analogous to reading a planet’s biography. Planets are more than mass and orbit; atmospheres hold the evidence.

Why exoplanet atmospheres matter is that they reshape our understanding of planetary origins, the chances for life beyond Earth, and the societal returns of big science investments. Below are eight concrete reasons, grouped into three themes: fundamental science, habitability and the search for life, and practical and societal impacts. Keep reading to see how a planet’s air rewrites stories about worlds far from home.

Expanding Fundamental Planetary Science

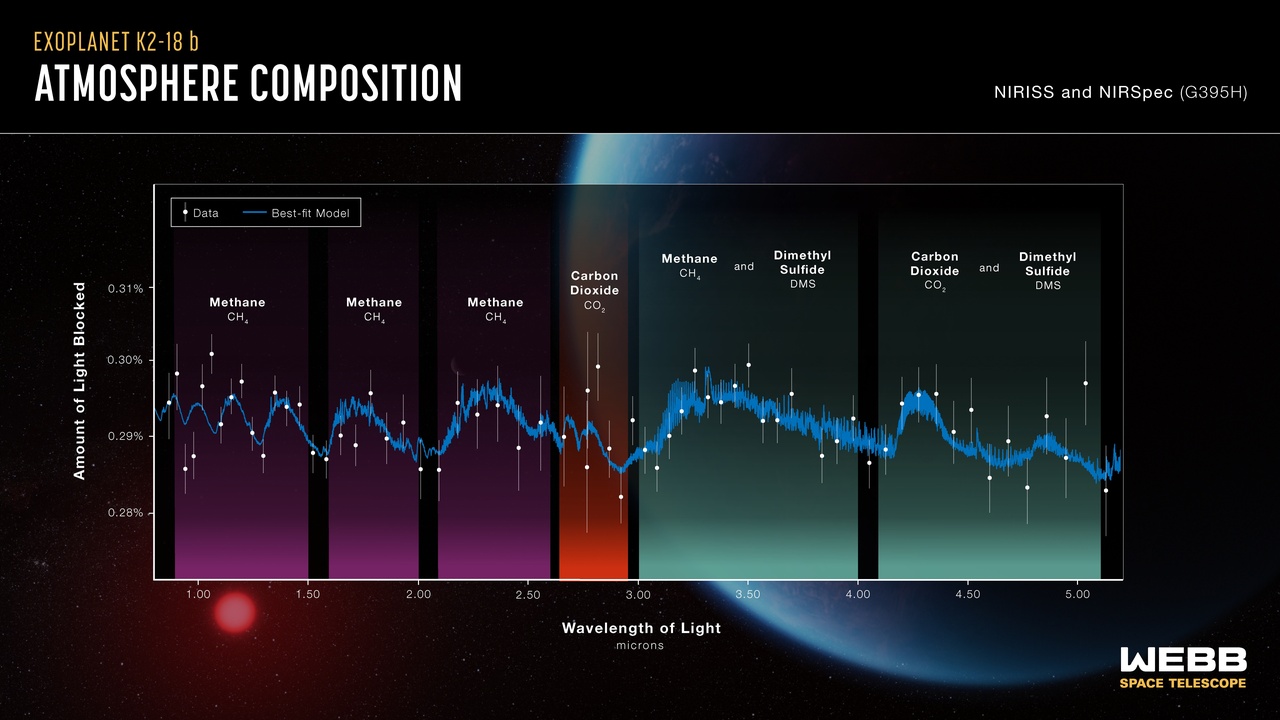

Atmospheric measurements give direct, often surprising evidence about a planet’s composition, formation path and dynamical history. Instruments from Hubble and Spitzer to ground-based spectrographs like HARPS and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) make those measurements by resolving molecular and atomic signatures in transmitted, emitted, or reflected light.

That information refines classification beyond mass and radius, challenges formation models, and tells us which systems are highest priority for deeper study. Early JWST results, such as the clear detection of CO2 in WASP-39b, illustrate how rapidly the field is moving from detection to detailed chemistry.

Across more than 5,500 confirmed exoplanets, atmospheric spectroscopy is the tool that turns catalog entries into physical worlds with stories to tell about where and how they formed.

1. Reveals composition and chemical fingerprints

Spectroscopy literally reads atmospheric composition: molecules such as H2O, CO2, CO, and atoms like Na and K show up as identifiable features in a spectrum. JWST’s detection of carbon dioxide on WASP-39b and earlier Hubble detections of water vapor on several hot Jupiters are concrete examples.

Those chemical clues constrain where a planet accreted its gas and solids, whether it captured material from a protoplanetary disk or migrated through it, and which worlds deserve follow-up for habitability. With more than 5,500 confirmed exoplanets in the catalog, targeted atmospheric follow-up lets us prioritize the most informative cases.

2. Helps classify worlds beyond size and orbit

Planets that look similar by radius can be very different in atmosphere. Properties like mean molecular weight, cloud opacity, and scale height separate rocky super-Earths from gas-rich mini-Neptunes.

The radius valley discovered by Fulton et al. in 2017 — a gap around roughly 1.6 Earth radii — points to atmospheric loss as a key process. Atmospheres explain why two planets near the same size diverge: one retains a light envelope, the other is stripped to a rocky core.

That distinction is practical: knowing which small planets still host atmospheres focuses resources for future missions searching for biosignatures.

3. Tests planet formation and migration theories

C/O ratios, enrichment in heavy elements (metallicity), and trace species are diagnostics of formation location and accretion history. A high C/O ratio, for example, can indicate formation beyond the water-ice line or selective accretion of carbon-rich solids.

The very existence of hot Jupiters — starting with 51 Pegasi b in 1995 — forced theorists to include migration mechanisms. Hot Jupiters remain rare around Sun-like stars (order of ~1% occurrence), and their atmospheres help test whether they moved inward gently through a disk or via dynamic scattering.

Comparative metallicity measurements between exoplanetary gas giants and our Solar System’s Jupiter and Saturn help calibrate core-accretion models and the timing of gas capture versus solid growth.

Probing Habitability and the Search for Life

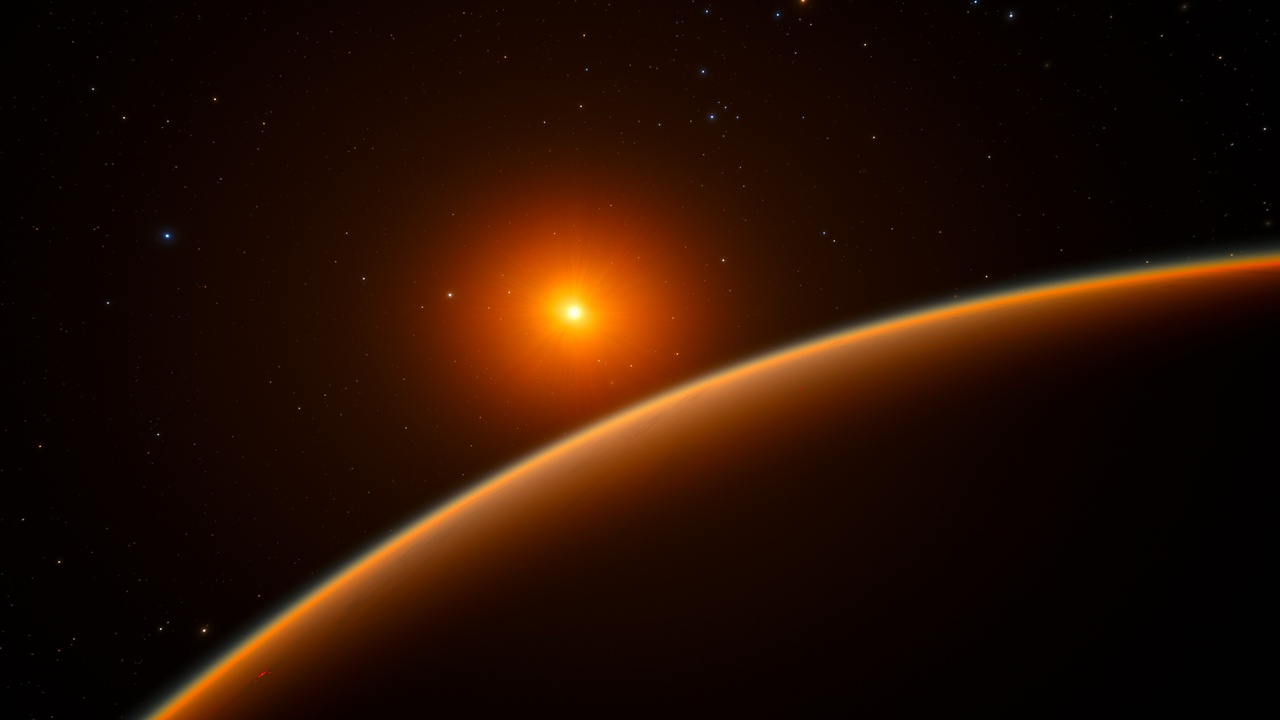

Atmospheres are the interface between a planet and any surface life: they regulate temperature, shield harmful radiation, and carry gases that could indicate biology. But interpreting those gases requires careful context because abiotic chemistry can mimic biological signatures.

The TRAPPIST-1 system (seven Earth-size planets discovered in 2016) is a prime laboratory for atmosphere studies around small, cool stars. Mapping atmospheres there and elsewhere will tell us how often temperate, Earth-sized planets actually maintain stable, life-supporting climates.

Upcoming 30–40m ground telescopes and further JWST follow-ups will push sensitivity toward the molecular signatures needed to distinguish biological from non-biological processes.

4. Finds potential biosignatures

A biosignature is a detectable feature — typically a gas or pattern of gases — that is plausibly produced by life. Common candidates include oxygen (O2), ozone (O3), methane (CH4), alongside water (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2).

TRAPPIST-1e is one of the most promising terrestrial targets discovered in 2016, but detecting biosignatures will demand high signal-to-noise spectra and multiple lines of evidence to rule out false positives from photochemistry or volcanic outgassing.

Confident claims will require caution: simultaneous detections of complementary molecules and knowledge of the planet’s irradiation, pressure and surface conditions minimize misinterpretation.

5. Maps climate and weather on other worlds

Atmospheric observations let us infer temperature distributions, wind patterns and cloud coverage remotely. Techniques such as phase-curve photometry and eclipse mapping turn changing light into global maps.

For some hot Jupiters, day–night temperature contrasts exceed 1,000 K. WASP-43b’s phase-curve observations revealed extreme east–west shifts and strong day-night contrasts, illustrating how circulation redistributes heat on tidally locked planets.

These mapping methods will scale down toward cooler, smaller planets, providing crucial inputs to habitability assessments for terrestrial worlds.

6. Provides context for Earth’s uniqueness

Comparing exoplanet atmospheres to Earth quantifies how special our planet’s mix is. Earth’s atmosphere is roughly 21% oxygen by volume, with CO2 around 420 ppm (≈0.042%) and a nitrogen-dominated background — a combination shaped by biology and geophysics.

Atmospheric evolution models applied to exoplanets can produce analogs of Earth’s Archean past, when oxygen was much lower, helping us understand possible pathways for life to alter a planet’s air.

Those comparative studies address a central question: are temperate, Earth-like atmospheres common outcomes of planet formation or rare products of a narrow set of circumstances?

Technology, Economy, and Broader Impacts

Why exoplanet atmospheres matter also shows up in the real-world returns: the pursuit of faint molecular signals pushes detector, telescope and data-analysis technology, funds teams and training programs, and creates international partnerships that extend beyond astronomy.

Major missions and facilities — from HARPS and ground-based high-resolution spectrographs to JWST (NIRSpec and MIRI) — require cutting technical capabilities: stable spectrographs, low-noise infrared detectors and cryogenics, and ultra-precise pointing systems.

Those investments spin off into medical imaging, remote sensing, and other industries, while citizen-science platforms and public outreach broaden participation and build the STEM pipeline.

7. Drives telescope and instrument innovation

The technical demands of atmosphere studies drive advances: high-stability spectrographs, improved infrared detectors, cryocoolers and adaptive optics systems all advance because astronomers need ever-better sensitivity. JWST, launched Dec 25, 2021, exemplifies that push.

With an approximate mission investment on the order of $10 billion, JWST’s instruments (NIRSpec, MIRI) enable measurements like WASP-39b’s CO2 feature and set new requirements for detector performance.

Those technologies have concrete spin-offs: infrared detector improvements inform medical imaging and night-vision systems, while precision pointing and cryogenic engineering find uses in satellites and industry.

8. Inspires workforce development and international collaboration

Atmosphere research funds multidisciplinary teams and trains students in optics, data science, and systems engineering. Large missions are multinational by design — JWST is a partnership between NASA, ESA and CSA — and those ties foster long-term collaboration.

Citizen science projects such as Planet Hunters on Zooniverse engage thousands of volunteers, while data from more than 5,500 confirmed exoplanets provide rich material for student projects and public outreach.

The result is a steady pipeline of STEM-trained people, international agreements on shared datasets, and broader public literacy about science and space investment.

Summary

- Atmospheric spectra act as chemical fingerprints that reveal formation histories and migration paths.

- Atmospheres differentiate otherwise similar planets and explain features like the Fulton radius valley (~1.6 R⊕).

- Biosignature searches require multiple molecules and contextual climate data to avoid false positives.

- Mapping temperatures and winds (e.g., WASP-43b) shows how diverse planetary climates can be.

- Investments in instruments (JWST, HARPS, NIRSpec, MIRI) produce technological spin-offs, jobs and international partnerships (NASA/ESA/CSA).

Follow upcoming JWST follow-ups and developments for the ELT/GMT/TMT, and consider supporting public science efforts or joining projects like Planet Hunters to engage directly with discovery.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.