When Galileo trained his telescope on Jupiter in 1610 he revealed four moons that transformed our view of the solar system — and among them was Callisto, a heavily cratered world that’s often dismissed as a dull rock. At about 4,820 km across, Callisto is nearly as large as Mercury, yet it rarely gets the spotlight reserved for Europa or Ganymede. That glossing-over misses something important: Callisto combines an ancient, well-preserved surface with practical advantages for exploration, making a strong case for why Callisto is underrated. This piece lays out six evidence-backed reasons—scientific value, habitability and exploration benefits, and mission-design advantages—that argue for giving Callisto more attention in future outer-planet plans.

Scientific Value: A Time Capsule of the Early Solar System

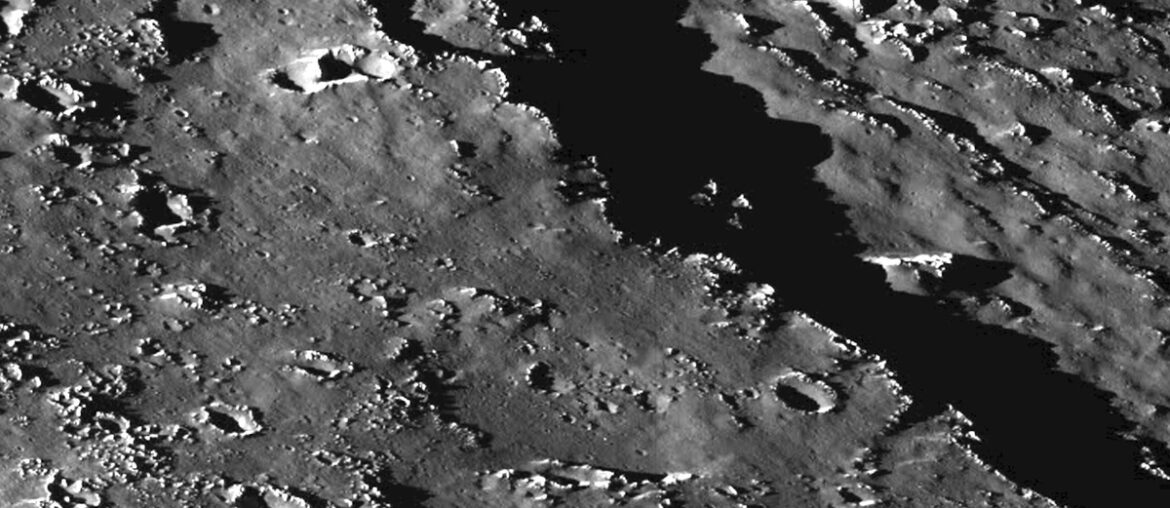

Callisto’s heavily cratered exterior preserves a near-pristine record of impacts and surface processes from the first billion years of the solar system. Flyby imagery from Voyager in 1979 and then the Galileo orbiter (1995–2003) showed a surface dominated by craters and multi-ring basins rather than the tectonic or resurfaced terrains seen on its siblings. That antiquity complements, rather than duplicates, studies of Europa’s young ice shell and Ganymede’s complex geology: together the Galilean moons sample very different evolutionary paths. With a mean density near 1.83 g/cm³, Callisto’s mix of rock and ice and its ~4,820 km diameter provide crucial context for models of how Jupiter’s satellites accreted and how impactor populations evolved across the system.

1. A preserved ancient surface — a window into 4.5-billion-year history

Callisto’s surface is among the oldest in the solar system, carpeted by impact craters that have changed little over billions of years. Voyager 1 and 2 (1979) first revealed the dense crater population; Galileo imagery between 1995 and 2003 provided higher-resolution views of the surface and basin morphology. Because it lacks large-scale resurfacing, crater retention is high, letting scientists use crater counts to estimate relative ages. Its diameter (~4,820 km) and low mean density (~1.83 g/cm³) point to a roughly equal mix of rock and water ice, a composition that preserves impact scars rather than erasing them through endogenic activity. Researchers use Callisto’s preserved record to refine models of early impact flux, which in turn calibrates our understanding of terrestrial planet bombardment and the formation histories of exoplanetary systems.

2. A record of bombardment — clues about the Late Heavy Bombardment and crater formation

Large multi-ring basins on Callisto—most notably Valhalla—record high-energy collisions that are windows into the population of early solar-system impactors. Valhalla’s outer rings span on the order of thousands of kilometers (estimates near ~3,800 km across), a scale that speaks to collisions far more energetic than typical modern impacts. Planetary scientists apply crater-counting methods and basin stratigraphy on Callisto to help calibrate timelines such as the Late Heavy Bombardment (~3.9 billion years ago). Those constraints refine models of how many planetesimals remained after planetary formation and how impactor flux varied from the inner to the outer solar system, improving estimates for Earth’s early environment as well as for other worlds.

Exploration and Habitability Advantages

Beyond pure science, Callisto offers practical advantages that make it an attractive target for future missions. At an orbital radius of roughly 1,882,700 km from Jupiter, Callisto sits well outside the planet’s most intense radiation belts, so spacecraft and potential habitats need far less heavy shielding than at Europa or Io. Models and Galileo-era data also leave open the possibility of a subsurface layer or local volatile deposits. Those two traits—lower radiation and accessible volatiles—make Callisto both a safer staging ground for long-duration operations and an astrobiologically interesting target that contrasts with the tidal-heated environments of inner Galilean moons.

3. Relatively low radiation — safer for long-duration operations

Callisto’s distance from Jupiter places it outside the worst of the planet’s magnetospheric radiation. For comparison, Io orbits at ~421,700 km, Europa at ~671,000 km, Ganymede at ~1,070,000 km and Callisto at ~1,882,700 km. Radiation flux falls steeply with distance and with reduced trapping in Jupiter’s field, so long-lived landers or habitats on Callisto would face substantially lower dose rates than similar installations at Europa. Lower radiation reduces the shielding mass required for electronics and human crews, which in turn lowers launch and mission costs. That radiation environment makes Callisto a realistic candidate for a robotic logistics hub or even a human-supporting outpost to enable exploration of the Jovian system.

4. Possible subsurface ocean — an astrobiology target with a different context

Although Callisto lacks the strong tidal heating that keeps Europa’s ocean lively, gravity and magnetic induction measurements from Galileo left room for a partially differentiated interior and the possibility of a subsurface, perhaps saline, layer in some models. Estimates vary—some scenarios allow for ice shells tens to hundreds of kilometers thick with pockets of liquid beneath—so the internal state is less certain than for Europa. That uncertainty is valuable: if Callisto hosts pockets of liquid, their formation and persistence mechanisms would differ from Europa’s tidal-driven ocean, offering a contrasting astrobiological laboratory. Studying both kinds of environments expands our view of the conditions where life might arise and persist.

Engineering, Economic and Mission Design Benefits

From a mission-planning perspective, Callisto’s stable surface, lower radiation and simpler orbital dynamics translate to concrete savings and engineering simplicity. Its surface is cold and largely inactive, making landings and long-lived infrastructure less risky than on geologically active moons. Ice and rock mixed near the surface point to in-situ resources that could support propellant production and life support. Those attributes let mission designers achieve high science return while controlling cost and complexity—especially if Callisto is integrated into broader mission architectures that visit multiple Jovian moons.

5. A practical site for staging and in-situ resource use (ISRU)

Surface temperatures on Callisto average around 120 K (≈ −153°C), which preserves water ice at or near the surface and makes ISRU concepts feasible. Extracting water for life support and splitting it into hydrogen/oxygen propellant could dramatically reduce the mass that needs to be launched from Earth. Because Callisto’s geology is relatively inactive, landing sites can be chosen for logistical convenience rather than for geological risk mitigation, and long-lived infrastructure faces fewer surprises. Lower shielding requirements also shrink habitat mass, so combined ISRU and reduced-shield approaches offer meaningful mass and cost savings for missions deeper into the Jovian system or for sample-return architectures aimed at inner solar-system targets.

6. High scientific return at comparatively low mission cost — overlooked by major programs

Despite Voyager flybys in 1979 and detailed Galileo observations from 1995–2003, Callisto has never hosted a dedicated orbiter or lander. Contemporary flagship efforts have focused elsewhere: ESA’s JUICE (launched 2022) targets Ganymede while carrying Callisto flybys, and NASA’s Europa Clipper (planned for the mid-2020s) concentrates on Europa. Adding Callisto-specific legs or modest payloads to multi-moon missions could yield disproportionate new science for relatively low incremental cost. Given the existing data foundation and Callisto’s logistical advantages, mission planners would get substantial additional return by including Callisto in mixed mission profiles.

Summary

Callisto combines a preserved early-solar-system record with exploration-friendly conditions—low radiation, accessible ices and practical mission geometry—making it both a valuable scientific target and a pragmatic staging ground. Past missions (Voyager 1979; Galileo 1995–2003) have set the stage, and upcoming programs like JUICE (launch 2022) offer opportunities to deepen our understanding. Given modest additions to mission plans, Callisto could deliver high science and logistical payoff.

- Ancient, heavily cratered surface preserves impact histories that help calibrate early solar-system timelines (Valhalla basin as a key example).

- Orbital distance (~1,882,700 km) keeps radiation levels low compared with Europa and Io, lowering shielding and cost for long-duration instruments or habitats.

- Possible subsurface liquid or volatile pockets offer an astrobiological test case distinct from Europa’s tidally heated ocean.

- Stable cold surface (≈120 K) and accessible ices make Callisto well suited for ISRU and logistics hubs that could enable broader Jovian exploration.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.