On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon and uttered words that turned a human achievement into an immutable piece of history.

Some records are mere milestones that future missions may surpass, while others are fixed either by the laws of physics or by singular historical firsts. The first class—immutable physical limits—comes from well-tested constants and thermodynamic laws. The second class—unique human firsts—are single events with cultural and historical value that can’t be repeated as a “first.”

This article lists twelve such unbreakable examples, grouped into three categories: Fundamental physical limits, cosmic timeline limits, and irreplaceable human milestones. Read on to see the limits set by nature and the moments set by history, starting with the bedrock laws of physics.

Fundamental Physical Limits

These records derive from well-tested physical laws and fundamental constants, so they represent absolute or practically unattainable limits. Below, each entry explains the physical reason the limit cannot be surpassed and why that matters for technology and science.

1. The Universal Speed Limit: The Speed of Light (c)

The speed of light in vacuum is exactly 299,792,458 m/s, and according to special relativity nothing with rest mass can reach or exceed it.

Einstein’s 1905 formulation of special relativity set the framework: as an object with mass accelerates toward c its relativistic energy and required fuel diverge. Practical systems reflect this limit—GPS satellite timing and particle accelerator design both include relativistic corrections tied directly to c.

Occasional experimental anomalies have appeared—most famously the 2011 OPERA neutrino result—but careful checks found measurement errors rather than superluminal particles. Causality, communications, and propulsion concepts all rest on this immutable numeric value: 299,792,458 m/s.

2. The Unattainable Cold: Absolute Zero (0 K)

Absolute zero, 0 K (−273.15°C), is the theoretical lower bound on temperature; the Third Law of Thermodynamics implies it cannot be reached in a finite number of steps.

Laboratory breakthroughs have pushed effective temperatures into the nano- and pico-Kelvin regimes for ultracold atomic gases and Bose–Einstein condensates, but each increment requires exponentially more effort. Superconductivity research and quantum computing depend on these extreme cold techniques to reduce decoherence and thermal noise.

Recent experiments have reported temperatures measured in the picoKelvin range for certain trapped ultracold systems, yet those are asymptotic approaches rather than attainment of 0 K. The Third Law guarantees that absolute zero remains a boundary, not a finish line.

3. The Smallest Meaningful Distance: Planck Length (~1.616×10⁻³⁵ m)

The Planck length is roughly 1.616×10⁻³⁵ meters and marks the scale at which classical notions of space break down and quantum gravity effects should dominate.

Planck units arise by combining Newton’s G, the speed of light c, and the reduced Planck constant ħ. Below the Planck length our current theories lack the language to describe geometry reliably, so distances smaller than this lose classical meaning.

Practical consequences follow: particle accelerators cannot probe arbitrarily smaller scales because the energies required would approach or exceed Planck energy, and no experiment under known physics can resolve distances near 10⁻³⁵ meters. That makes the Planck length a true theoretical lower bound.

4. The Shortest Meaningful Time: Planck Time (~5.39×10⁻⁴⁴ s)

The Planck time, about 5.39×10⁻⁴⁴ seconds, is the smallest time interval at which the usual concepts of time and causality remain meaningful under our current theories.

It’s derived from the same trio of constants (G, c, ħ). Physics as presently formulated cannot reliably describe events earlier than one Planck time after the putative Big Bang because quantum gravitational effects become dominant and classical spacetime may not exist.

Cosmologists and quantum-gravity researchers therefore treat Planck time as a boundary for predictive models; statements about “before” one Planck time are speculative without a full theory of quantum gravity.

Cosmic Timeline Limits

These records are set by the Universe’s history—earliest moments and observational horizons that give absolute bounds on age and what we can see. Dates and distances anchored to the Big Bang define unbreakable limits on time and observation.

5. The Oldest Possible Age: Age of the Universe (~13.8 Billion Years)

The best current estimate for the age of the Universe is about 13.799 ± 0.021 billion years, based on Planck satellite measurements of the cosmic microwave background.

Planck’s 2018 results, cross-checked with WMAP and other probes, give a robust figure that sets an absolute upper limit: nothing in existence can be older than the Universe itself. Stellar ages, globular cluster estimates, and radioactive decay measurements must fit below this ceiling.

That age anchors models for structure formation, stellar evolution, and the timeline of chemical enrichment across cosmic history.

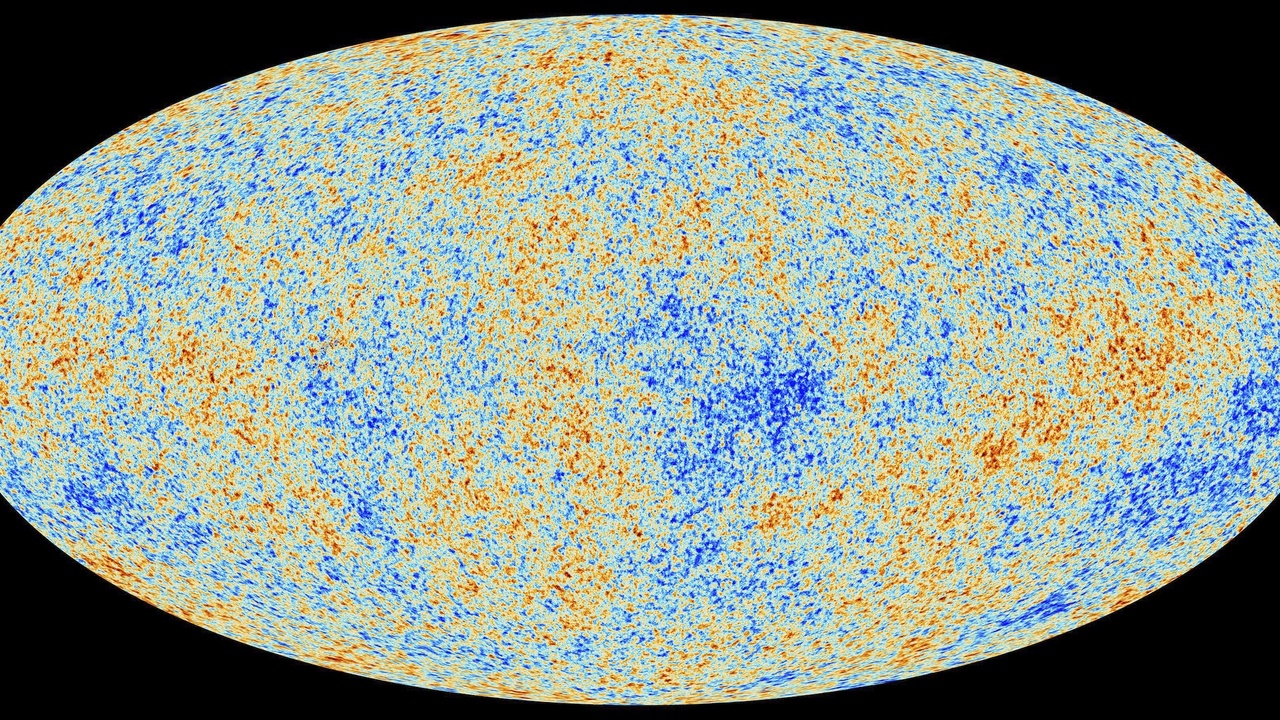

6. The Earliest Light: Cosmic Microwave Background (≈380,000 years after the Big Bang)

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is the oldest electromagnetic radiation we can observe: photons that last scattered about 380,000 years after the Big Bang and now appear as a 2.725 K blackbody.

Observations by COBE, WMAP, and Planck measured the CMB’s spectrum and tiny anisotropies, providing the data that anchor cosmological parameters such as curvature, matter content, and the initial fluctuation spectrum.

Because the CMB photons were released at recombination, we cannot observe earlier electromagnetic signals; the CMB thus establishes a firm observational boundary for photon-based astronomy.

7. The Limit of What We Can See: The Observable Universe (~46.5 Billion Light-Years Radius)

The observable universe extends roughly 46.5 billion light-years in every direction from Earth; that particle horizon is the radius beyond which light has not had time to reach us since the Big Bang.

Cosmic expansion stretches space so that proper distances today exceed naive light-travel times, and light from regions beyond the particle horizon cannot ever reach us. This is an observational limit, not a physical wall: the Universe may extend far beyond what we can see.

For cosmology and survey planning, the particle horizon sets a hard cap on the volume available for direct observation and on the sample of galaxies we can study.

8. The Earliest Element Factory: Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (~3 Minutes After the Big Bang)

Primordial nucleosynthesis produced the light elements roughly three minutes after the Big Bang, synthesizing hydrogen, helium, and trace lithium in a one-time cosmological process.

The theory predicts a helium mass fraction of about 24–25%, and that prediction matches astronomical measurements. Those abundances set the chemical initial conditions for later star formation and galaxy evolution.

Because BBN was a brief early-Universe episode, its outcome cannot be repeated or altered without changing fundamental cosmological parameters; the observed light-element ratios remain a fixed record of early conditions.

Irreplaceable Human Milestones

Some unbreakable records are historical firsts—single events that by definition cannot be repeated as a “first.” Those moments shaped public memory, spurred policy and funding, and shifted entire technical programs.

9. First Artificial Satellite: Sputnik 1 (October 4, 1957)

Sputnik 1 was the first artificial satellite; it launched on October 4, 1957, and had a mass of approximately 83.6 kg with a simple radio transmitter that produced the famous beeps.

The launch stunned the world, triggered the space race, and led directly to rapid investments in science and engineering education. The U.S. response included Explorer 1 and, eventually, the creation and expansion of space agencies and research programs.

That single “first satellite” moment cannot be superseded—the historical fact of Sputnik 1’s date and its role in global geopolitics is unique.

10. First Human in Space: Yuri Gagarin (April 12, 1961)

Yuri Gagarin became the first human to reach space aboard Vostok 1 on April 12, 1961, completing one orbit in a flight lasting about 108 minutes.

Gagarin’s flight proved that humans could survive launch, microgravity, and reentry, and it established procedures and protocols that informed later human spaceflight operations. The mission’s symbolic and political resonance remains unique.

As the inaugural human spaceflight, Vostok 1’s place in history cannot be replaced by later, longer, or more complex missions—it is the first.

11. First Human on the Moon: Apollo 11 (July 20, 1969)

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were the first humans to land on and walk the Moon on July 20, 1969; Armstrong’s line “That’s one small step for [a] man…” became shorthand for human exploration.

The first EVA on the lunar surface lasted about 2.5 hours during that initial moonwalk, and Apollo 11 returned approximately 21.6 kg of lunar samples to Earth for scientific study.

Apollo 11’s combination of timing, personnel, and mission sequence makes it an irreplaceable milestone. Later lunar missions built on its legacy, but none can claim that “first human on the Moon” status.

12. First Woman in Space: Valentina Tereshkova (June 16, 1963)

Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space on June 16, 1963, aboard Vostok 6, with a mission duration of about 2.98 days.

Her flight had wide symbolic impact, inspiring women in engineering and science and demonstrating human adaptability in orbital conditions. Tereshkova’s achievement remains a singular historical first that cannot be re-staged as a first.

Subsequent female astronauts and cosmonauts owe part of their public recognition and programmatic opportunities to that breakthrough moment in 1963.

Summary

Unbreakable records in space fall into two broad types: those enforced by fundamental physics, and those fixed by historical sequence. Planck scales and constants like the speed of light set absolute physical boundaries that experiments and technology must respect, while single “firsts” such as Sputnik, Gagarin, and Apollo 11 remain unique chapters in human history.

Recognizing these differences sharpens how we think about ambition and limitation—there are targets to push within the laws of nature, and there are moments to honor that changed our trajectory. Keep asking questions about the cosmos and the limits it imposes; curiosity is the engine that turns fixed boundaries into meaningful inquiry about the Universe and our place in it.

- The speed of light and Planck units act as absolute physical ceilings for motion, distance, and time measurements.

- Cosmic milestones—Universe age, the CMB, and the particle horizon—define what can ever be observed or dated.

- Historical firsts like Sputnik, Gagarin, and Apollo 11 are permanently singular and shape public memory and policy.

- Studying these limits deepens scientific practice and inspires questions about what we can learn next about space and physics.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.