7 Reasons to Explore Venus

On March 1, 1966, the Soviet probe Venera 3 became the first human-made object to impact another planet when it struck Venus. That blunt encounter marked humanity’s first physical contact with our nearest planetary neighbor and set a pattern: Venus rewards bold, technically difficult missions with outsized scientific returns.

Readers should care because Venus holds direct lessons for Earth’s climate, drives technology that has everyday uses, and still ranks as a plausible place to search for life — not on the surface, but in its clouds. Its similarities in size and composition to Earth make its differences all the more instructive: studying Venus sharpens climate models, informs how we interpret exoplanets, and accelerates materials and sensor advances back home.

This article lays out seven concrete benefits of renewed exploration — grouped into scientific discovery, astrobiology/atmospheric science, and technology/societal gains — to show why now is the moment to return to Venus.

Scientific Discovery and Planetary Context

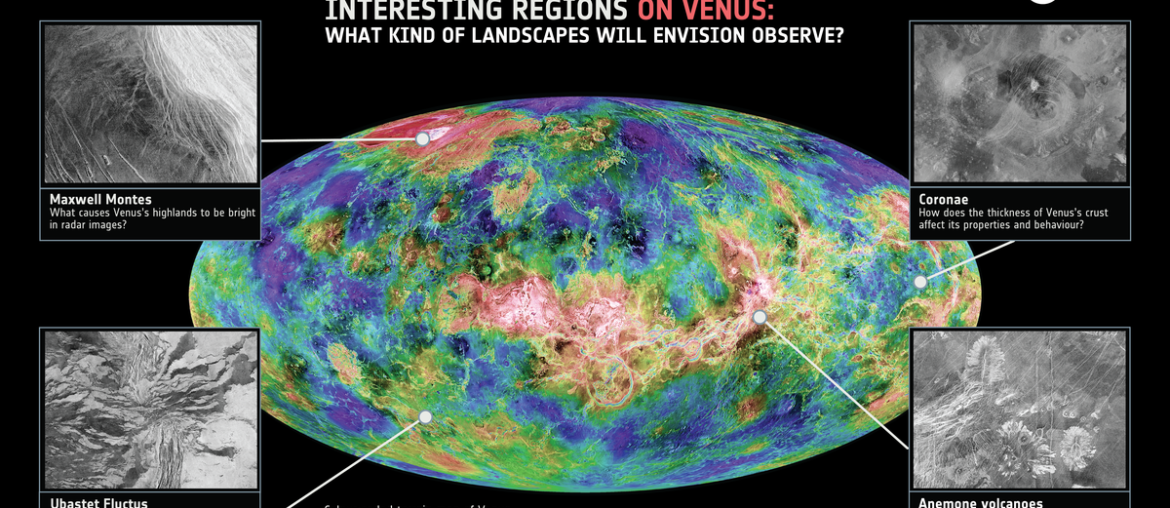

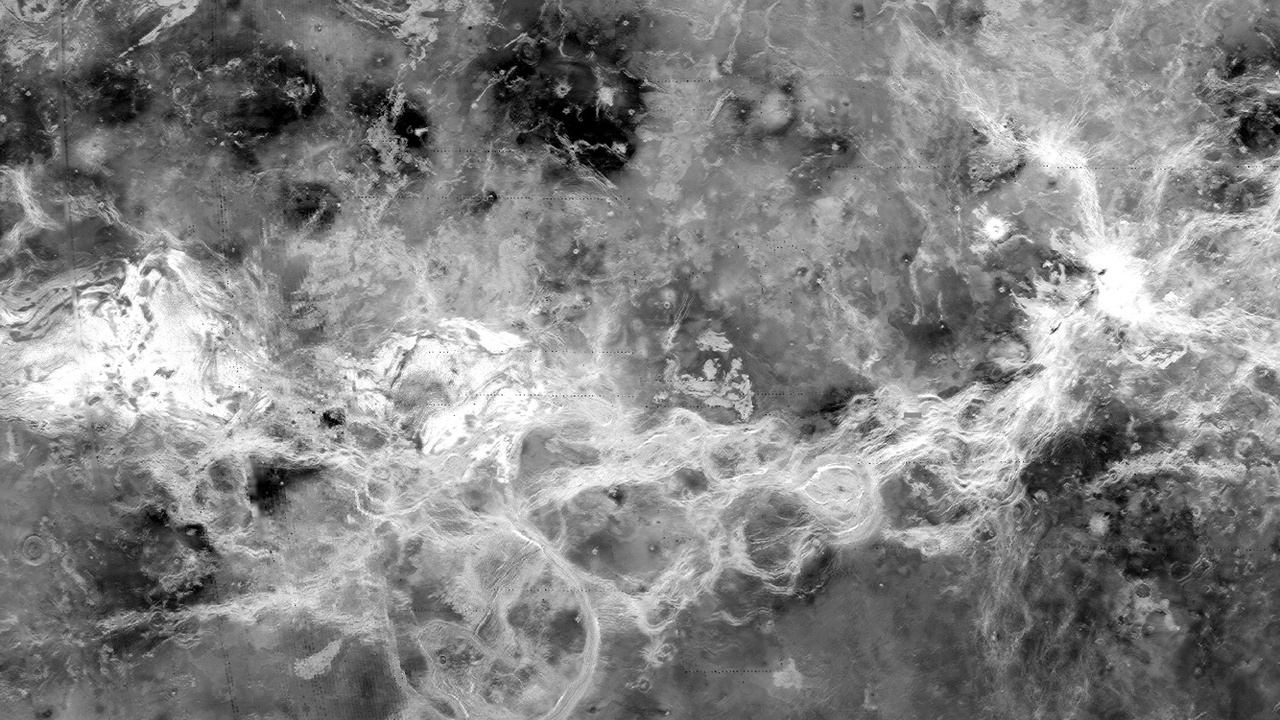

Venus is a natural laboratory for planetary science because it’s Earth’s near-twin in mass and radius but wildly different in climate and surface conditions. Surface temperatures average about ~465°C and pressures near ~92 bar, yet its bulk composition and age estimates for much of the crust are similar enough to make direct comparisons meaningful. Among the reasons to explore venus is improving models of rocky-planet evolution: Venus offers a counterexample to Earth’s path, helping test theories about volatile loss, tectonics, and atmospheric evolution that we then apply to exoplanets. Past missions like NASA’s Magellan (radar mapping in the early 1990s), ESA’s Venus Express, and JAXA’s Akatsuki provided crucial datasets; future missions can fill remaining gaps and tie Venus into the broader story of terrestrial worlds.

1. Understanding runaway greenhouse effects

Venus is the prime example of a runaway greenhouse atmosphere. Its mean surface temperature of roughly 465°C and surface pressure around 92 bar illustrate how greenhouse feedbacks can push a planet to an extreme, stable state very different from its starting point. Data from missions such as the Soviet Venera probes, NASA’s Pioneer Venus, and Magellan’s radar mapping underpin those measurements.

Scientists use Venus observations to calibrate climate models — for example, refining thresholds for when CO2-and-water feedbacks produce irreversible warming. Models that incorporate Venus data help constrain carbon-cycle behavior and inform estimates of how much extra forcing might tip a planet into runaway heating. That makes Venus indispensable for evaluating worst-case scenarios in Earth’s long-term climate planning and for interpreting hot rocky exoplanets detected around other stars.

2. Clues to Earth’s past and future

Venus may once have hosted significant surface water: measurements show an elevated deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio (D/H) roughly 100× that of Earth, consistent with massive water loss. Geological and atmospheric modeling suggests major water loss may have occurred billions of years ago, changing its climate trajectory early in solar-system history.

Studying how and when Venus lost its water — from isotopic measurements to models of hydrogen escape — gives us concrete analogies for long-term climate and habitability evolution. Missions like Pioneer Venus and later spacecraft have provided the baseline data; new missions can pin down timelines and mechanisms, improving our ability to predict how terrestrial planets evolve under different solar and atmospheric conditions.

Astrobiology and Atmospheric Science

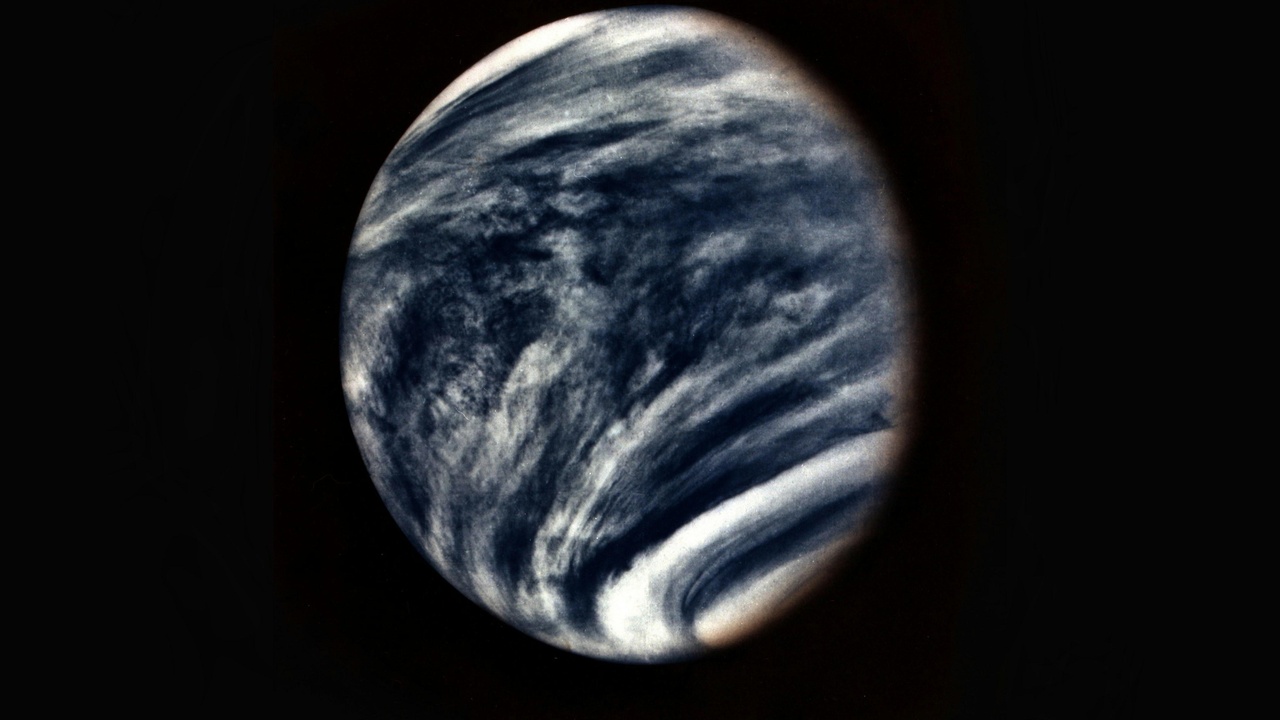

Venus presents a paradox: an ultra-hostile surface but cloud decks at about 50–60 km altitude with pressures and temperatures more like Earth’s. Those temperate layers are acidic — sulfuric acid droplets dominate — yet they create potential aerial niches worth investigating. The 2020 phosphine detection headline and the debate that followed vividly illustrate how controversial claims can re-energize targeted follow-up science. Below are two focused reasons tied to life-search and to atmospheric chemistry.

3. Searching for life in the clouds

There’s a practical benefit to looking for life in Venus’s clouds: at ~50–60 km altitude you find pressures near 1 bar and temperatures roughly in the 0–75°C range depending on altitude—conditions that can, in principle, support microbes. The catch: cloud droplets are rich in concentrated sulfuric acid, which would require any life to be highly acid-tolerant or to occupy microenvironments buffered from the acidity.

The 2020 phosphine announcement (Greaves et al., 2020) spurred intense follow-up — multiple teams reanalyzed the data and conducted new observations, showing the scientific process at work even when initial claims remain contested. Proposed mission concepts such as balloons, long-duration aerobot platforms, and cloud-sampling descent vehicles could directly sample aerosols and trace gases to test for biosignatures. Finding even suggestive biological markers would revolutionize biology and planetary science; null results would still tighten constraints on abiotic chemistry in hostile, but temperate, aerial habitats.

4. Understanding atmospheric chemistry and dynamics

Venus’s atmosphere challenges theory: the whole atmosphere super-rotates, circling the planet in about ~4 Earth days while the surface rotates much more slowly. Upper-atmosphere winds can reach ~100 m/s, and intense sulfur chemistry and cloud-formation processes produce layers and aerosols that are still not fully explained.

Missions such as ESA’s Venus Express and JAXA’s Akatsuki have delivered key observations — Akatsuki found stationary gravity waves and complex cloud tracers — but more in situ measurements of composition, vertical mixing, and lightning are needed. Understanding these processes improves atmospheric models for Venus, provides test cases for interpreting spectroscopic signals from exoplanets, and feeds back into Earth atmospheric science where comparable physical processes appear on different scales.

Technology, Exploration, and Societal Benefits

Venus missions force engineers to solve extreme problems — high temperatures, crushing pressures, and corrosive chemistry — producing technologies that spin off to Earth industries. One of the reasons to explore venus is the tangible tech development pathway: high-temperature electronics, pressure housings, and aerobot designs that have applications in energy, manufacturing, and harsh-environment sensing while also educating the next generation of engineers.

5. Advancing high-temperature materials and electronics

Standard silicon electronics fail quickly on Venus’s surface, so exploration drives development of high-temperature semiconductors like silicon carbide (SiC), novel pressure housings, and new thermal control approaches. The Soviet Venera landers provide a benchmark: Venera 13 landed in March 1982 and transmitted for about ~127 minutes before succumbing to the environment.

Modern proposals aim for far longer survival using SiC electronics, refractory materials, and innovative cooling or passive thermal designs. These technologies have Earth-side use: downhole drilling electronics, turbine sensors that operate at high temperatures, and industrial monitoring systems in severe environments. Each Venus mission pushes material and electronics readiness levels that industry can adopt.

6. Testing entry, descent, and surface operations for extreme worlds

Venus is an exceptional testbed for entry, descent, and landing (EDL) systems that must operate in a dense, hot atmosphere. Parachutes, aeroshells, and thermal protection must be sized for higher dynamic pressures; surface-sampling mechanisms must cope with abrasive regolith and corrosive chemistry. The Venera series demonstrated both successes and hard lessons in EDL; those lessons inform designs for future landers and for probes to giant planets.

EDL research on Venus also cross-applies to missions that enter dense atmospheres elsewhere — for example, designs for giant-planet probes or sample-return missions that face unusual thermal loads. Concrete development areas include improved thermal protection materials, robust heat-shield aerodynamics, and parachute fabrics rated for extreme shear loads.

7. Economic and scientific spin-offs back on Earth

Investment in Venus missions produces practical returns beyond pure discovery: remote-sensing advances, materials transferred to industry, and workforce development. For instance, radar-imaging techniques honed by Magellan have direct applications in Earth observation and resource monitoring. High-temperature materials research benefits energy and manufacturing sectors.

Major missions also hire and train large teams — agencies like NASA often engage hundreds of engineers and scientists on flagship missions — creating a pipeline of skilled professionals who move into industry and academia. These spin-offs justify public investment: improved tools for climate modeling, new industrial sensors, and an expanded technical workforce deliver measurable societal value.

Summary

The case for returning to Venus is practical and immediate: it advances planetary science, probes possible aerial biospheres, and accelerates technologies that benefit life on Earth.

- Venus is a climate laboratory — its ~465°C surface and ~92 bar pressure show what runaway greenhouse states look like.

- Cloud decks at ~50–60 km offer temperate pressures and temperatures, making the search for aerial biosignatures a high-payoff objective (2020 phosphine debate highlighted by Greaves et al.).

- Technology driven by Venus missions — SiC electronics, high-temp materials, radar techniques — spins off to industry and Earth observation.

- Entry, descent, and surface operations on Venus sharpen capabilities for other extreme missions and train a workforce of engineers and scientists.

- Follow near-term mission opportunities — NASA’s DAVINCI+ and VERITAS — and stay updated via NASA and ESA mission pages to see how these reasons to explore venus translate into real missions and benefits.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.