In 1995 astronomers announced the first confirmed planet orbiting a Sun-like star: 51 Pegasi b. That discovery rewired how scientists look for worlds beyond Earth and launched a hunt for environments that might host life.

Searching for life matters on multiple levels: it answers a fundamental scientific question about biology’s distribution in the cosmos, it drives engineering advances (from precision instruments to sample-return systems), and it reshapes culture and philosophy. As of 2023 more than 5,000 exoplanets have been confirmed, giving researchers a large sample to assess how common habitable conditions might be.

Promising places for life beyond Earth are identified by a few core ingredients: persistent liquid solvents, energy gradients to power chemistry, complex organic molecules, and the potential for detectable biosignatures. Missions and telescopes — including the Europa Clipper and the James Webb Space Telescope — are now designed to test those criteria directly.

This list ranks the 10 most compelling sites where astrobiologists expect to find signs of life, organized into four groups: ocean worlds, rocky neighbors, nearby exoplanets, and unusual niches. Each entry explains why the target is scientifically interesting and which missions or discoveries make it high priority.

Ocean Worlds in the Outer Solar System

Subsurface oceans rank near the top of astrobiology priorities because they combine stable liquid water with chemical interfaces and sustained energy sources. Ice shells can protect internal oceans for billions of years, while tidal heating from giant planets provides a long-lived energy budget that drives hydrothermal activity and chemical gradients.

That logic was bolstered by spacecraft data: Cassini sampled Enceladus’s plumes starting in 2005, and Galileo’s magnetic and imaging data revealed signs of salty oceans beneath Europa and Ganymede. Because some moons vent material into space, missions like Europa Clipper (planned launch 2024) can probe internal chemistry without drilling through kilometers of ice.

Below are three ocean-world targets with different advantages for detecting life.

1. Europa — Icy shell over a global ocean

Europa is a top candidate because a global salty ocean lies beneath a relatively thin, fractured ice shell. Galileo’s magnetic field measurements and surface geology from the late 1990s–early 2000s imply a conductive, salt-rich layer under the ice, and surface features suggest recent resurfacing.

A subsurface ocean tens to perhaps hundreds of kilometers deep could host microbial ecosystems where rock meets water, especially if tidal heating drives hydrothermal chemistry. Europa Clipper will carry ice-penetrating radar and mass spectrometry instruments to map the ice shell and search for surface–ocean exchange zones that could yield detectable biosignatures.

2. Enceladus — Active plumes with sampled organics

Enceladus is unique because it actively vents material from a subsurface ocean into space, creating a direct sampling opportunity. Cassini’s plume flythroughs beginning in 2005 detected water vapor, ice grains, salts and complex organics, and follow-up analyses in 2015 found molecular hydrogen — a potential chemical energy source for microbes.

Because plume material is launched into space, a mission can analyze ocean-derived compounds via flybys or sample return without penetrating the ice. That accessibility, combined with Cassini’s clear indications of organics and energy, makes Enceladus a high-probability site for biosignature searches.

3. Ganymede — The largest moon with its own magnetic field

Ganymede likely harbors a subsurface ocean beneath complex, layered ice and is the only moon known to generate its own intrinsic magnetic field. Galileo data and later Hubble observations point to a differentiated interior with one or more ocean layers and a magnetosphere that alters how charged particles interact with the surface.

Ganymede’s size and magnetic shielding could influence habitability by moderating radiation at the ice surface and shaping chemical transport. ESA’s JUICE mission is currently en route to study Ganymede and will probe its ice shell, magnetosphere and potential ocean, improving our understanding of how these factors affect biosignature preservation.

Rocky Neighbors: Mars and Venus

Inner solar system rocky planets remain essential to the search because they offer direct access to past or niche habitable environments. Mars preserves extensive evidence for ancient surface water, while Venus records a dramatic climate evolution that could have included habitable surface conditions and might host chemical niches in its cloud decks.

Robotic campaigns are designed to look for preserved biosignatures: Mars rovers are caching samples for eventual return to Earth, and renewed interest in Venus after the 2020–2021 phosphine debate has led to missions like DAVINCI+ and VERITAS that plan to sample the atmosphere and map geology.

Two rocky neighbors deserve special attention.

4. Mars — The best-studied rocky candidate

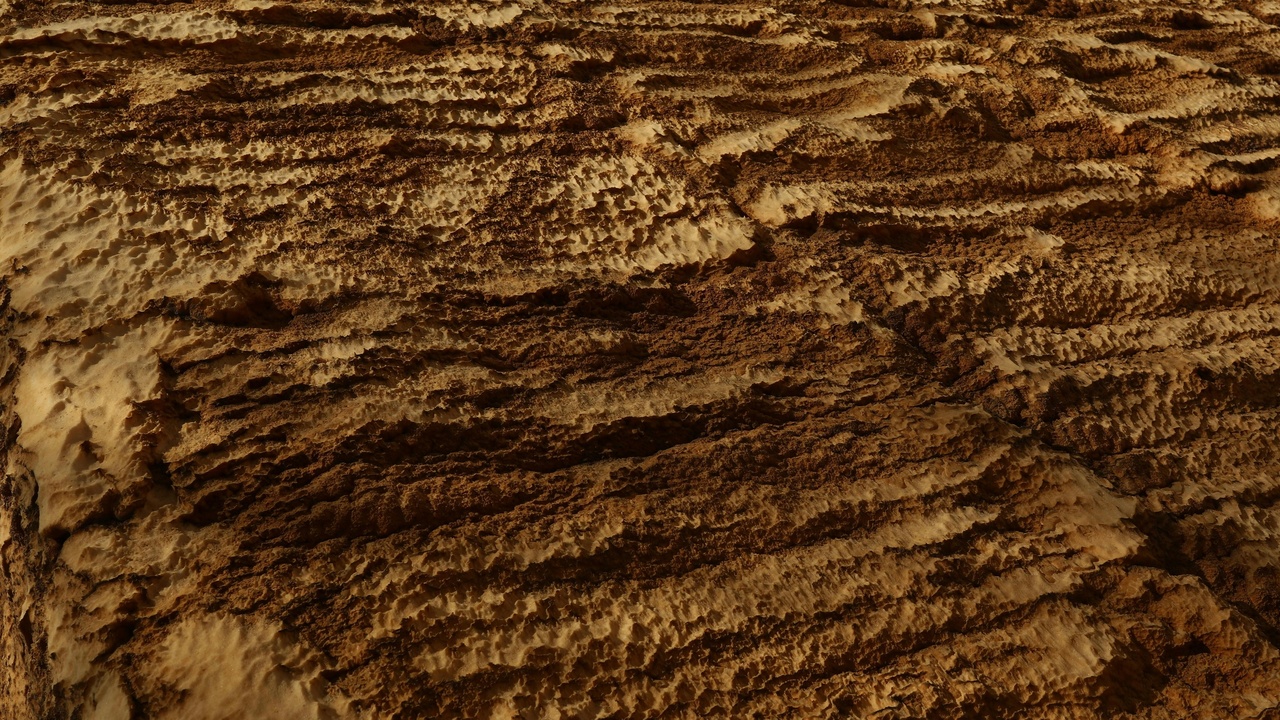

Mars is compelling because valley networks, lakebeds and mineralogical evidence show that rivers and lakes existed and created long-lived habitable environments. Clay minerals and sulfates preserve chemical records of neutral to mildly acidic waters that could trap organic matter.

Perseverance landed in February 2021 and is collecting rock cores for a future Mars Sample Return campaign, while Curiosity revealed ancient lake environments and detected organic molecules. Those missions push technologies for drilling, contamination control and lab-grade instruments needed for sensitive biosignature tests.

5. Venus — Cloud decks and a once-habitable past

Today Venus is hot and acidic at the surface, but its dense atmosphere and runaway greenhouse history imply a very different past. Some scientists argue Venus may have had oceans billions of years ago, and the cloud layer at about 50–60 km altitude has temperate temperatures where aerosols could, in principle, provide niches for microbial life.

The phosphine detection debate in 2020–2021 sparked renewed investigation into atmospheric chemistry and possible microscopic life in the clouds. Upcoming missions such as DAVINCI+ and VERITAS aim to sample atmospheric composition and map surface geology to search for traces of a wetter past.

Nearby Exoplanets in the Habitable Zone

Advances in telescopes and spectroscopy have moved certain nearby exoplanets from speculation to observational targets. With JWST launched in 2021 and next-generation extremely large telescopes coming online, atmospheric characterization of temperate worlds is now feasible for the closest systems.

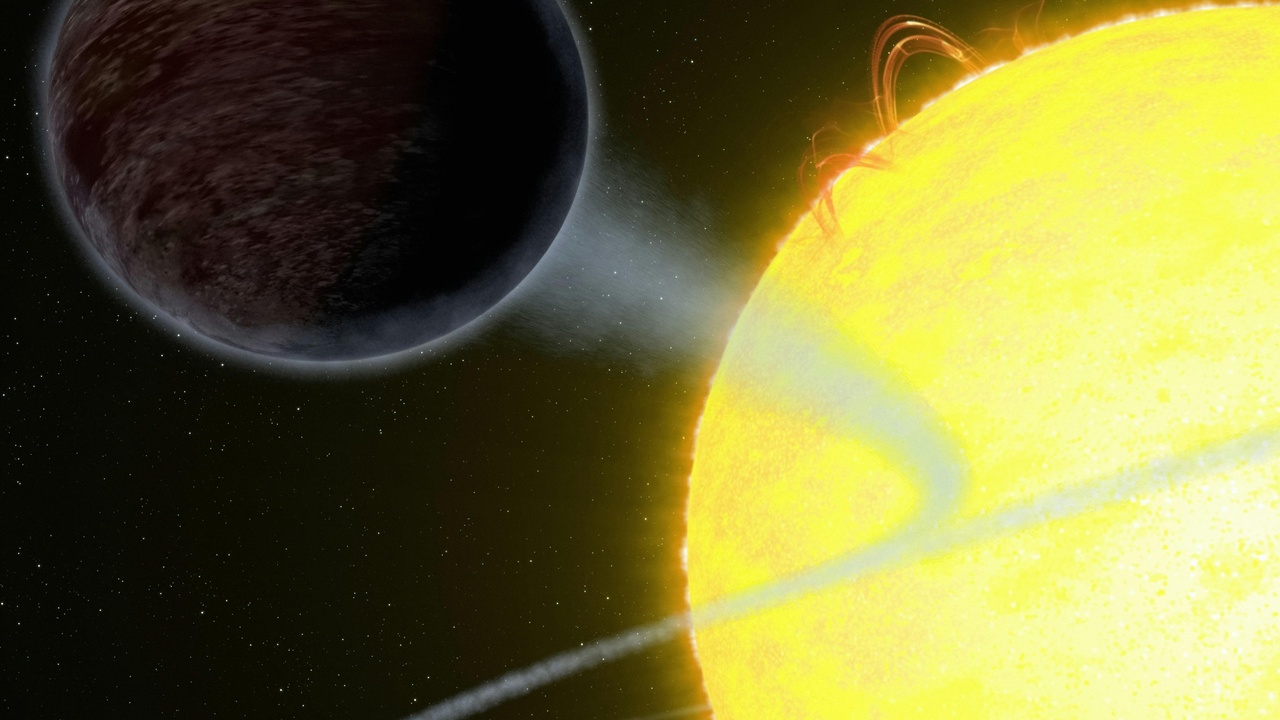

As of 2023 there are over 5,000 confirmed exoplanets, and researchers prioritize planets with the right size, stellar insolation and a chance of retaining an atmosphere. These nearby exoplanets rank among the most promising places to find alien life because biosignature gases could be detected through transmission or direct spectroscopy.

Three exoplanet targets stand out for proximity and observability.

6. Proxima Centauri b — Nearest temperate rocky world

Proxima Centauri b orbits the nearest star to the Sun and lies near the classical habitable zone, making it a compelling target. Discovered via radial velocities in 2016, the planet has a minimum mass comparable to Earth’s, though its exact composition and atmosphere remain unknown.

Proximity is its biggest asset: spectral observations with JWST and future ELTs could search for atmospheric features, while stellar activity and flares from Proxima complicate surface habitability. Still, being the closest temperate rocky world makes it a vital test case for atmosphere-detection techniques and future probe concepts.

7. TRAPPIST-1e — An Earth-size world in a compact system

TRAPPIST-1e sits in a system of seven Earth-size planets discovered in 2017, and it lies comfortably in the host star’s temperate zone. The system’s transit geometry and multiple similar planets make it excellent for comparative planetology and for testing how stellar environment shapes atmospheres.

Transit spectroscopy during repeated transits allows sensitive searches for atmospheres and biosignature gases; Hubble and JWST observations are already providing constraints. Having seven Earth-size planets discovered in 2017 in one nearby system gives researchers a rare laboratory to compare planets formed in the same disk.

8. Kepler-186f — The first Earth-size habitable-zone find

Kepler-186f is historically important as the first Earth-size planet found in a star’s habitable zone, announced in 2014. It orbits a cool M-dwarf and demonstrated early on that small planets in temperate orbits exist around low-mass stars.

While Kepler-186f is more distant and challenging to study than the nearest systems, the Kepler mission’s discovery reshaped expectations about how common small habitable-zone planets are and helped guide the design of follow-on surveys and instruments.

Unusual but Promising Niches

Life might also exist where our initial assumptions about habitability are stretched. Titan, dwarf planets and small bodies host rich organic chemistry, and comets or interstellar visitors deliver and preserve primitive molecules. Studying these niches widens the search and tests alternative solvents, energy sources, and preservation pathways for biosignatures.

Past missions have already surprised us: Huygens landed on Titan in 2005, Rosetta detected organics on comet 67P in 2014, and Dawn revealed briny deposits at Ceres in 2015. Such findings motivate missions that probe chemistry rather than assuming Earth-like surface water is necessary.

Two examples illustrate why unusual niches belong on any prioritized list.

9. Titan — Organic chemistry in hydrocarbon seas

Titan is remarkable for a dense nitrogen atmosphere, surface lakes of methane and ethane, and a rich inventory of complex organics. The Huygens probe in 2005 and Cassini’s extended mission revealed dunes, river channels, and seasonal weather driven by hydrocarbons.

Though Titan’s liquid is non-water, it provides a natural laboratory for prebiotic chemistry and for exploring how life might exploit different solvents. NASA’s Dragonfly rotorcraft mission will visit Titan’s surface in the mid-2030s to investigate organic chemistry and potential habitable niches.

10. Comets and interstellar visitors — Mobile organic labs

Comets, asteroids and interstellar objects carry and preserve primordial organics and volatiles, acting as time capsules from the era of planet formation. Rosetta’s 2014 measurements of comet 67P revealed complex organic molecules, while the 2017 discovery of ‘Oumuamua highlighted that material can travel between star systems.

Sample-return missions have made this tangible: Hayabusa2 returned samples from asteroid Ryugu (2020) and OSIRIS‑REx collected material from Bennu for return in 2023. Laboratory analysis of such samples lets scientists search for amino acids, chirality signatures and other markers that inform origins-of-life scenarios.

Summary

- Ocean worlds like Europa and Enceladus offer long-lived liquid water and, in Enceladus’s case, plume sampling that makes direct biosignature searches feasible.

- Mars and Venus present complementary rock‑record and atmospheric niches, with Perseverance sample caching and upcoming Venus missions enabling targeted analyses.

- Nearby exoplanets enable atmospheric biosignature hunts with JWST and ELTs, increasing the number of realistic targets for remote detection.

- Small bodies and unusual environments—Titan’s hydrocarbon seas, icy dwarf-planet brines, comets and interstellar visitors—broaden how we define habitable worlds and preserve complex organics.

- Support for missions, participation in citizen science with exoplanet data, and following mission results are the best ways for the public to stay engaged as we search for places to find alien life.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.