In 1988 astronomers led by Lynden-Bell and colleagues reported a surprising bulk motion: our Local Group is drifting at roughly 600 km/s toward a region of the sky with no obvious single massive object. That measurement, deduced from galaxy redshift catalogs and the Cosmic Microwave Background dipole, pointed to a large-scale gravitational pull now popularly known as the Great Attractor.

This is not just a curiosity. That hidden tug affects how we map mass in the nearby universe, biases local estimates of cosmological parameters, and tests our models of how structure forms on tens to hundreds of megaparsecs. Peculiar velocities of galaxies—motions over and above the Hubble expansion—carry a direct imprint of where mass sits, including dark matter we can’t see directly.

Despite decades of work, the mysteries of the great attractor remain. Below are seven core puzzles—grouped into observational, physical, and cosmological/future-research categories—that explain why the region resists a single tidy explanation and why incoming surveys matter.

Observational puzzles around the Great Attractor

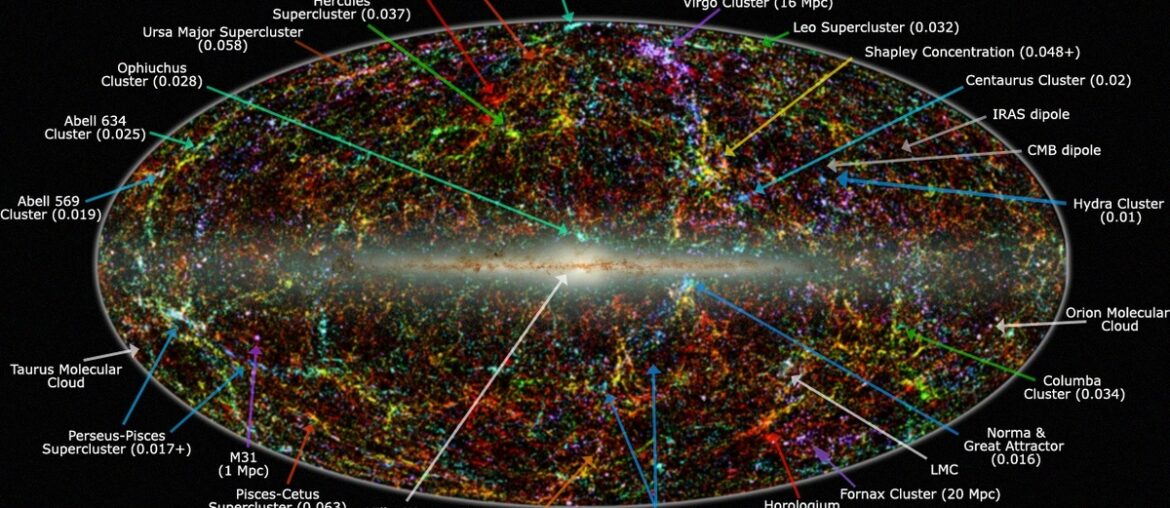

This group covers mysteries that arise from what we can and cannot observe. The Milky Way’s disk hides a substantial swath of the sky in optical bands—the so-called Zone of Avoidance—which hampers straightforward maps of nearby mass. Different windows (infrared, radio HI, X-ray) pierce parts of that veil, and large redshift and peculiar-velocity datasets (for example 2MASS/2MRS and the various Cosmicflows releases) give complementary but sometimes conflicting views.

Key historical context helps here: Lynden-Bell et al. first quantified the bulk flow toward the attractor region in 1988, and subsequent surveys like 2MASS (late 1990s/early 2000s), ROSAT (1990s) and modern Cosmicflows compilations have steadily improved coverage but left important gaps. Resolving what we can see — and what remains hidden — is essential before we can confidently assign mass to specific structures.

1. Why does our galaxy move toward an apparently empty patch of sky?

The puzzle is plain: the Local Group’s peculiar velocity of about 600 km/s, first quantified in 1988, points toward a region without a single obvious giant cluster centered on that exact spot. That velocity comes from combining redshift catalogs with a subtraction of the CMB dipole to isolate motion relative to the cosmic rest frame.

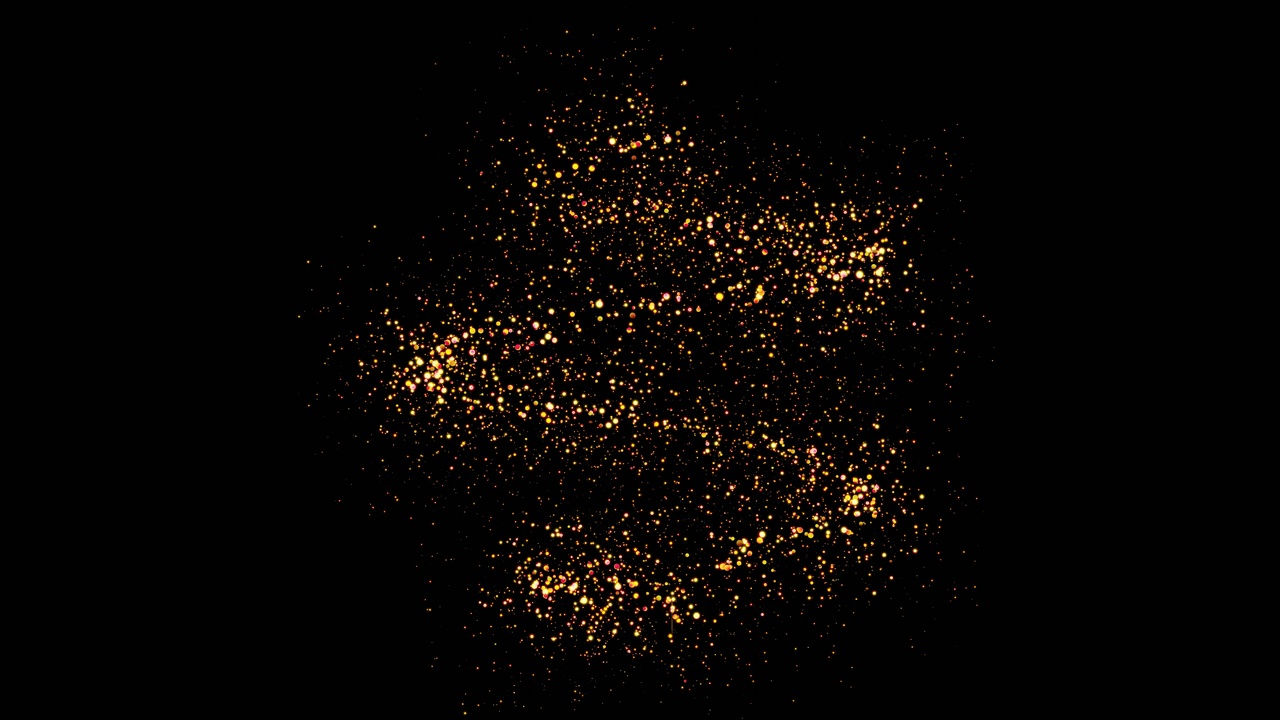

Bulk flows are measured using distance indicators—Tully–Fisher for spirals and Type Ia supernovae for calibrated explosions—then compared to redshift distances to extract peculiar velocities. Modern compilations such as the Cosmicflows datasets provide large samples that show a coherent flow toward the GA region, implying a substantial nearby mass concentration.

One concrete candidate identified through multiwavelength work is the Norma Cluster (Abell 3627), which emerged as a major mass concentration once infrared and X-ray data revealed it despite heavy foreground extinction. But Norma alone may not account for the entire measured flow, which is why this hidden tug remains puzzling.

2. How much is hidden behind the Milky Way’s Zone of Avoidance?

The Milky Way’s disk obscures roughly 20% of the extragalactic sky at optical wavelengths, creating the Zone of Avoidance and a real blind spot for traditional surveys. That fraction varies with latitude and wavelength, but the optical gap is large enough to bias density reconstructions if left uncorrected.

Infrared surveys such as 2MASS and its redshift extension 2MRS penetrate much of the dust that hides galaxies, while radio HI observations (Parkes multibeam surveys) find gas-rich galaxies behind the plane. X-ray missions like ROSAT (1990s) and the later eROSITA all-sky mapping (from 2019 onward) reveal hot cluster gas that is otherwise invisible optically. Together these windows have brought objects like Abell 3627 into view, but some obscured groups and filaments likely remain uncharted.

Missing data changes mass reconstructions and can skew peculiar-velocity inferences, so reducing the Zone of Avoidance is critical to getting the local density field—and thus local dynamics—right.

3. Is the Great Attractor one object or a superposition of structures?

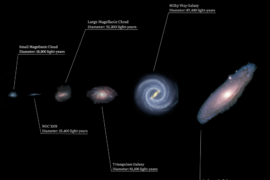

Do we have a compact, dominant mass at ~50–75 Mpc (roughly 150–250 million light-years) or a loose region of enhanced density made of multiple contributors? That’s a central observational ambiguity. Redshift surveys such as 2dF, 6dF and 2MRS produce reconstructed density fields that sometimes favor a nearby complex of clusters (Centaurus, Norma) and other times point to more extended contributions.

The Shapley Supercluster sits farther away—about 650 million light-years or ≈200 Mpc—and is massive enough that its pull may add to the local flow. Disentangling overlapping influences from Centaurus/Norma versus Shapley (and intervening filaments) is difficult because line-of-sight projection and incompleteness in the Zone of Avoidance can make separate structures appear to merge in redshift space.

Resolving whether the signal is dominated by a single attractor or a superposition of nearby and more distant concentrations is essential for accurate local mass estimates and for testing structure-formation models.

The physical nature of the unseen mass

On the scales relevant to the Great Attractor, total mass is usually dominated by dark matter, but pinning down the baryonic contribution and the overall mass profile remains tricky. Different probes—X-ray emission from hot intracluster gas, galaxy counts and luminosities, weak gravitational lensing, and dynamics from velocity fields—each sample different components and scales, and they don’t always agree.

Because methods sample different tracers and suffer distinct biases (projection, obscuration, sample variance), mass estimates for large attractor regions often span orders of magnitude. Combining multiple wavelengths and techniques is the only reliable way to converge on a consistent picture.

4. What is the true mass of the Great Attractor region?

Mass estimates change with methodology. Summing visible galaxies—using counts from infrared surveys like 2MASS/2MRS—gives one partial total; inferring mass from X-ray observations of hot intracluster gas (ROSAT, Chandra) yields another; dynamics derived from peculiar velocities and redshift-space distortions provide yet another. Typical quoted orders of magnitude for large attractor regions are 10^15–10^16 solar masses, but that’s a rough range.

Differences arise from sampling bias, projection effects along the line of sight, and obscuration by the Milky Way. Velocity-field reconstructions use the peculiar velocities of galaxies to infer the underlying density, but they require dense, accurate distance indicators to be reliable. Until multiwavelength data and dense peculiar-velocity samples align, the total mass and its dark-to-baryonic partition will remain uncertain.

Getting the mass right is more than bookkeeping: it changes predictions for local dynamics and the inferred distribution of dark matter in our cosmic neighborhood.

5. Could dark energy or cosmic expansion mask the true flow?

Gravity reigns on scales of a few to a few tens of megaparsecs, while cosmic expansion driven by dark energy dominates on the largest scales. Dark energy makes up roughly 68–70% of the universe’s energy density, and its influence means that beyond some scale the Hubble flow overwhelms local gravitational pulls.

The practical issue is that peculiar velocities are superimposed on cosmological expansion, and errors in separating the two propagate into measurements like the Hubble constant. Planck CMB analyses give H0 ≈ 67.4 km/s/Mpc, while local distance-ladder methods commonly find ~73 km/s/Mpc; local flows and biased sample locations can shift local H0 measurements by a few percent if not properly modeled.

Accurate modeling of local attractors and peculiar velocities—so we don’t mistake a gravitational pull for a cosmological signal—is therefore necessary to reconcile local and global measurements and to test Lambda-CDM on 50–100 Mpc scales.

Cosmological implications and how we’ll solve it

Looking forward, the Great Attractor is a test bench for theories of large-scale structure and for the Lambda-CDM paradigm. Simulations such as the Millennium runs provide expectations for how matter clusters on 50–200 Mpc scales, and nearby surveys give the empirical counterpart that either matches or challenges those predictions.

Upcoming and ongoing projects—Cosmicflows updates for peculiar velocities, Euclid and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory for enormous redshift and imaging samples, eROSITA for an X-ray cluster census, and Gaia for refining Milky Way foreground models—will dramatically reduce uncertainties. Combining wavelengths and techniques is the path to finally disambiguating local versus distant contributions to the measured flow.

6. What does the Great Attractor teach us about cosmic structure formation?

The Great Attractor sits at the interface between studies of the local universe and tests of hierarchical clustering. Its existence, amplitude and scale constrain how matter—dark and baryonic—has clustered in recent cosmic time. Comparing observed peculiar-velocity fields and reconstructed density maps to numerical simulations tests whether Lambda-CDM reproduces nearby structure statistics.

Surveys have made substantial progress: 2MRS contains roughly 43,000 galaxy redshifts that help map the local density field, and Cosmicflows catalogs provide thousands of peculiar-velocity measurements. Matching those observed fields to Millennium-style simulations gauges whether our models produce attractors of the observed strength and morphology on ~50–100 Mpc scales.

Discrepancies would prompt refinements in baryonic physics, halo bias models, or even in our understanding of how dark matter clusters at those scales.

7. How will upcoming surveys finally reveal the answer?

There’s reason for optimism. Euclid will map roughly 1.5 billion galaxies in optical and infrared bands out to z~2, providing a massive, uniform dataset for large-scale structure. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) will image billions of objects with deep, time-domain data; its full survey comes online in the mid-2020s. eROSITA, launched in 2019, is delivering an all-sky X-ray catalog of clusters that highlights massive objects even behind some Galactic dust. Gaia continues to refine foreground models by measuring stellar positions and motions to exquisite precision.

Combined, these projects will increase redshift and peculiar-velocity samples by orders of magnitude, fill in parts of the Zone of Avoidance using infrared and X-ray tracers, and provide weak-lensing and dynamical cross-checks on cluster masses. That multiwavelength, multi-technique approach should disentangle overlapping contributions like Centaurus/Norma versus Shapley and pin down whether the observed flow is local, distant, or both.

Expect major improvements over the next 5–10 years as these datasets mature and teams produce integrated reconstructions of the nearby density field.

Summary

- Lynden-Bell et al. (1988) first quantified a ≈600 km/s bulk flow toward an apparently empty patch, launching decades of work to explain that hidden tug.

- The Zone of Avoidance (∼20% of the optical sky) hides important structures; infrared (2MASS/2MRS), HI (Parkes), and X-ray (ROSAT/eROSITA) surveys have revealed key players like Abell 3627 (Norma).

- It’s unclear whether a single massive object or a superposition (Centaurus/Norma plus the more distant Shapley Supercluster) drives the flow; distance estimates place the main region at ~150–250 million light-years while Shapley lies near ~650 million light-years.

- Mass estimates vary by method (galaxy counts, X-ray gas, dynamics), but large attractor regions are often quoted at order 10^15–10^16 solar masses, with dark matter dominating the budget.

- Watch results from Euclid, the Vera Rubin Observatory, eROSITA and Cosmicflows over the next 5–10 years—those surveys should substantially clarify the mysteries of the great attractor and sharpen nearby cosmological measurements like H0.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.