In the 18th century, catalogers such as Charles Messier began listing fuzzy “nebulae” in the night sky—many of those entries are now recognized as some of the most famous star clusters viewed by amateur and professional astronomers alike. These collections of stars captured attention then and still do because they tell a story: how stars are born, how they age, and how galaxies assemble over billions of years.

Star clusters matter to casual stargazers for their beauty and ease of observation, and to scientists as distance indicators, testbeds for stellar evolution, and tracers of galactic history. Missions like ESA’s Gaia and the Hubble Space Telescope have transformed our view by mapping precise motions, resolving crowded cores, and measuring ages and chemical compositions.

Here are 10 of the most spectacular star clusters, and what each teaches us about the universe.

Classic Open Clusters

Open clusters are loosely bound groupings of dozens to thousands of generally young stars that live in a galaxy’s disk. They are nearby laboratories for stellar physics: by comparing stars that formed together we can test models of pre‑main‑sequence contraction, rotation, and chemical mixing.

Open clusters differ from globulars in age, mass and location—open clusters are younger, less massive, and sit in the disk, while globulars are ancient, massive, and occupy galactic halos. Modern surveys, notably ESA’s Gaia, have dramatically improved member lists and distances, while Hubble gives sharp detail on individual stars in crowded fields.

1. Pleiades (M45) — The Seven Sisters

The Pleiades, nicknamed the Seven Sisters, is a bright open cluster easily seen with the naked eye and through binoculars. It lies about 440 light‑years away and is roughly 100 million years old, with over a thousand stars cataloged and a handful of bright A‑type stars that dominate the visual scene.

Visually it’s spectacular because of the blue reflection nebulosity and the hot, luminous stars that scatter light. Scientifically the Pleiades serve as a benchmark for pre‑main‑sequence models; Gaia parallax measurements and Hubble imaging helped resolve a long‑running distance controversy and sharpened its role in calibrating stellar ages and distances.

2. Hyades — Our Nearest Open Cluster

The Hyades is the nearest open cluster to Earth at roughly 150 light‑years, forming the distinctive “V” in Taurus. Its age is about 625 million years and it contains some 300–400 confirmed members spread across a few dozen light‑years.

Proximity makes the Hyades invaluable for the distance ladder and proper‑motion studies: Gaia has measured individual stellar motions so precisely that members are cleanly separated from background stars. Historically it set luminosity calibrations used across stellar astronomy.

3. Beehive Cluster (Praesepe, M44) — A Springtime Favorite

Praesepe, the Beehive Cluster or M44, is visible to the unaided eye under dark skies and sits about 580–600 light‑years away. With an age near 600–700 million years, it contains several hundred stars and provides an intermediate‑age benchmark between very young nurseries and old globulars.

Astronomers use Beehive members to study stellar rotation and activity at intermediate ages, and to search for planets in clustered environments—several exoplanet searches have targeted cluster stars to learn how planet occurrence varies with environment. Amateurs enjoy it as an easy springtime telescopic object.

Stellar Nurseries and Young Massive Clusters

Young massive clusters and stellar nurseries are compact, very young groupings where massive stars form and profoundly shape their surroundings. These regions are where the most massive stars—O and early B types—form, emit intense ultraviolet radiation, and drive winds that sculpt gas and affect subsequent star formation.

Studying these clusters helps astronomers test high‑mass stellar evolution and feedback, probe the initial mass function, and understand how dense clusters might evolve into long‑lived systems. Hubble, ALMA and infrared telescopes (plus Gaia where extinction allows) are essential for resolving disks, outflows and crowded stellar cores.

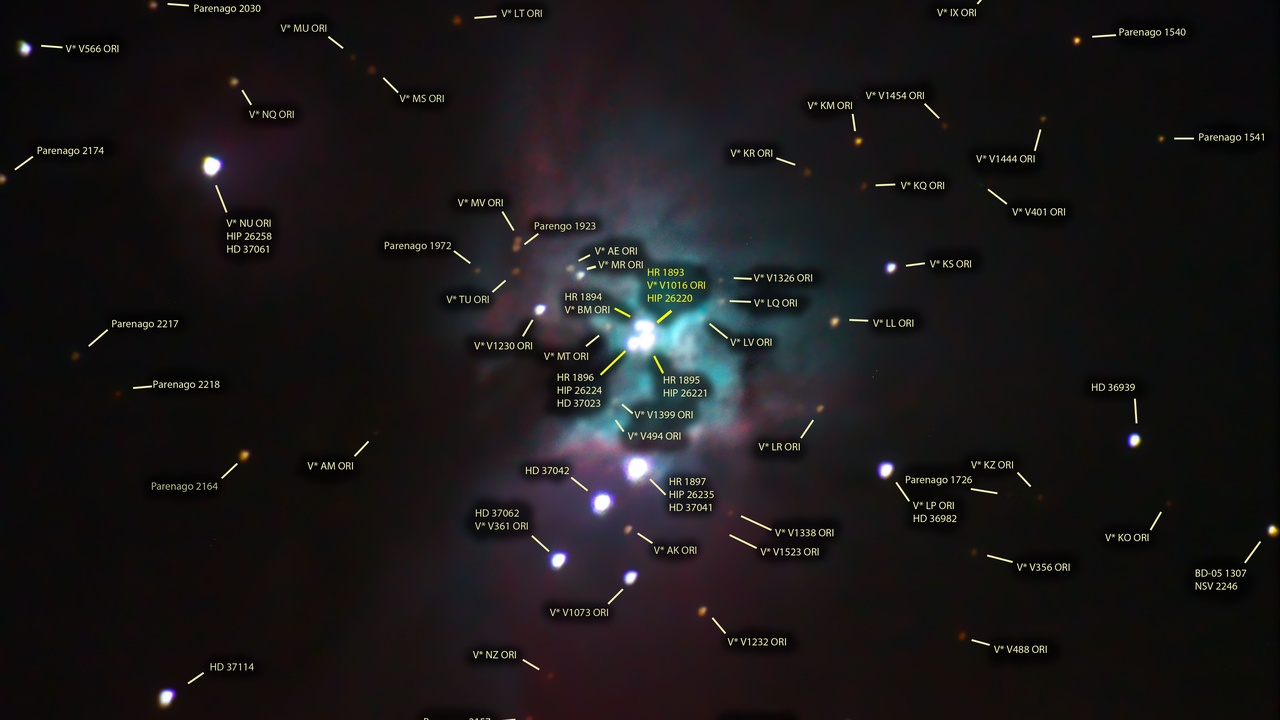

4. Trapezium Cluster (in Orion Nebula) — A Nearby Stellar Nursery

The Trapezium is the compact core of the Orion Nebula (M42), at about 1,350 light‑years and with ages of roughly 0.5–2 million years. Its bright O‑ and B‑type stars illuminate surrounding gas and reveal dramatic features.

Hubble imaging beginning in the 1990s unveiled dozens of protoplanetary disks—“proplyds”—and provided the first direct visual evidence that planet‑forming disks survive in harsh environments. ALMA and infrared follow‑ups continue to map disk masses and chemistry, making the Trapezium a prime laboratory for early stellar and planetary evolution.

5. NGC 3603 — A Dense, Massive Star Factory

NGC 3603 is one of the Milky Way’s most compact and massive young clusters, located about 20,000 light‑years away and only ~1–2 million years old. Its core contains many O‑type stars packed into a very small volume, producing intense ultraviolet radiation and powerful winds.

Hubble and ground‑based infrared observations pierce the dust to reveal a dense, starburst‑like environment that serves as a local analog to extragalactic super star clusters. Studies of NGC 3603 inform how massive clusters form and how stellar feedback regulates star formation in extreme conditions.

6. Westerlund 1 — One of the Galaxy’s Heaviest Young Clusters

Westerlund 1 is a heavily obscured but extremely massive young cluster discovered in the 1960s and studied in detail more recently. At about 16,000 light‑years and an age of roughly 3–5 million years, it hosts a remarkable population of evolved massive stars.

Infrared surveys (VISTA, Spitzer) are crucial for penetrating the dust and cataloging members. Westerlund 1 contains numerous red supergiants and Wolf–Rayet stars, making it a unique laboratory for short‑lived stellar phases and identifying likely supernova progenitors.

Globular Giants

Globular clusters are spherical, tightly bound systems containing hundreds of thousands to millions of mostly old stars in a galaxy’s halo. With ages around 10–13 billion years, they are among the oldest surviving stellar systems and thus trace the early stages of galaxy formation.

These clusters are dynamical laboratories: dense cores produce blue stragglers, X‑ray binaries and millisecond pulsars, and modern Hubble imaging plus Gaia kinematics reveal multiple stellar populations and detailed chemical patterns that tell of complex formation histories.

7. Omega Centauri (NGC 5139) — The Largest Milky Way Cluster

Omega Centauri is the Milky Way’s most massive and largest globular, at about 17,000 light‑years and roughly 150 light‑years across. It contains several million stars and has been studied extensively across the 20th and 21st centuries.

Its intrigue comes from multiple stellar populations and a spread in metallicity that suggest a complex past—perhaps the stripped core of a dwarf galaxy rather than a simple globular. Hubble and Gaia studies of its kinematics and populations make it central to understanding galactic assembly.

8. 47 Tucanae (NGC 104) — Dense and Pulsar‑Rich

47 Tucanae is one of the brightest, densest southern globulars, sitting about 15,000 light‑years away and aged around 11–12 billion years. Its crowded core conceals many compact objects that astronomers hunt for with radio and X‑ray telescopes.

Radio pulsar surveys have found dozens of millisecond pulsars in 47 Tuc, and Hubble resolves stellar populations even in the core. These exotic inhabitants inform studies of stellar dynamics, binary evolution, and extreme physics in dense environments.

9. M13 (Hercules Cluster) — A Northern Hemisphere Favorite

M13, the Hercules Cluster, is the best‑known northern globular and a staple for backyard telescopes. It lies at about 22,000 light‑years and contains several hundred thousand stars concentrated into a bright core.

William Herschel observed it in the 18th century, and modern instruments like Hubble have followed up to study blue stragglers and stellar dynamics. Its visual appeal and scientific utility make M13 a bridge between amateur observation and professional research.

Extragalactic Wonders

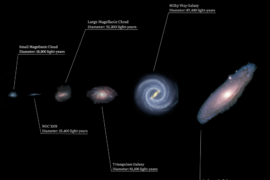

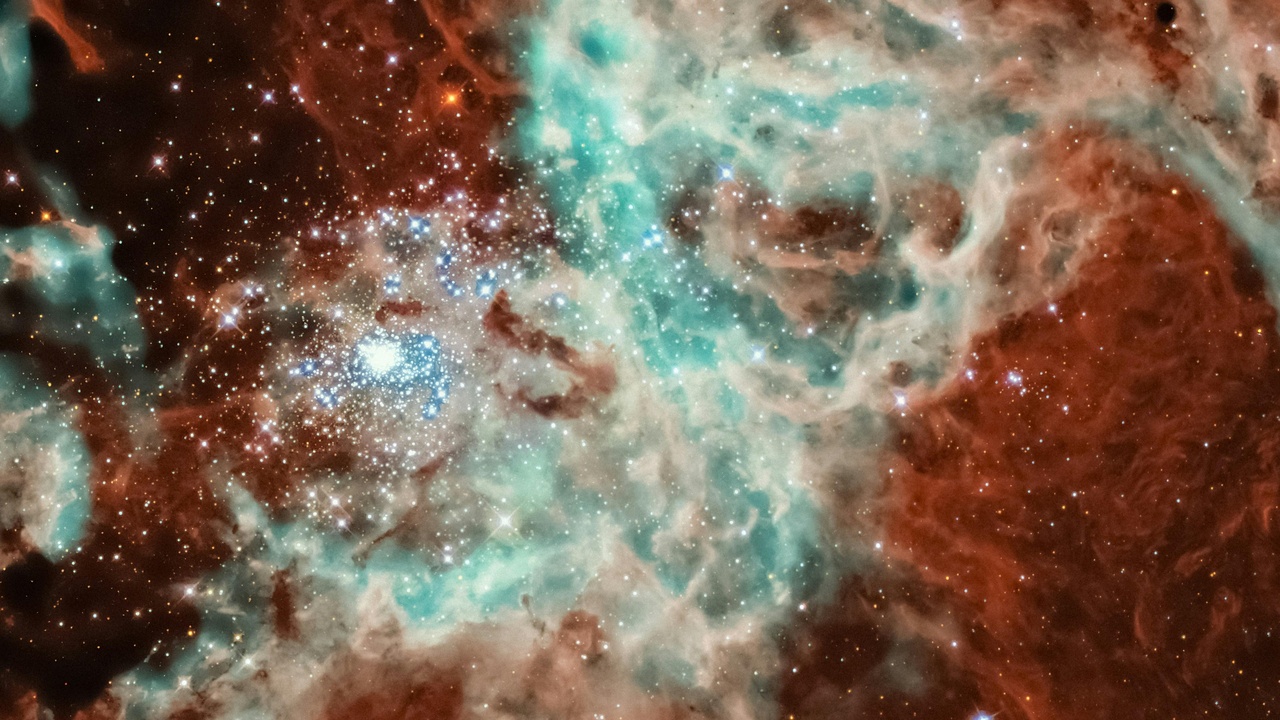

Some of the most revealing clusters lie beyond the Milky Way. Nearby galaxies, especially the Large Magellanic Cloud at about 163,000 light‑years, host clusters that formed under different metallicity and environmental conditions, so they test how stellar evolution changes with chemistry and density.

Among them, R136 ranks among the most spectacular star clusters known: its core contains extremely massive stars and provides a nearby example of the conditions found in starburst galaxies and the early universe.

10. R136 (in 30 Doradus, Large Magellanic Cloud) — A Super Star Cluster

R136 is the dense, young core of the Tarantula Nebula in the LMC, at about 163,000 light‑years and only ~1–2 million years old. Its mass and density are extreme compared with typical open clusters, and it hosts several of the most massive stars known—some initial masses are estimated above 100–150 solar masses.

Hubble resolved its crowded center, and spectroscopic work with the VLT and other facilities provided mass estimates and spectral classification. R136 tests the upper end of the initial mass function, shows how intense feedback shapes nebulae, and acts as a local analog for powerful extragalactic starbursts.

Summary

These ten clusters span an enormous range: ages from roughly 1 million to over 12 billion years, and distances from about 150 light‑years to 163,000 light‑years. Together they illuminate the life cycle of stars, from the fragile protoplanetary disks seen in the Trapezium to the crowded, ancient cores of globular giants like Omega Centauri.

Practically, they help calibrate distances (Hyades, Pleiades), test high‑mass stellar physics (NGC 3603, R136), and trace galaxy assembly through multiple stellar populations and kinematics (Omega Centauri, 47 Tucanae). Observing a nearby cluster with binoculars or following Gaia and Hubble releases (NASA, ESA) connects hobbyists to cutting‑edge research.

- Pleiades and Hyades are key distance and age benchmarks for stellar models.

- Trapezium, NGC 3603 and Westerlund 1 reveal how massive stars shape their birth environments and seed future supernovae.

- Omega Centauri and 47 Tucanae preserve clues to galaxy formation and host exotic objects like millisecond pulsars.

- R136 in the LMC shows that extreme star formation and very massive stars occur outside our Galaxy, offering a lab for starburst physics.

- Get outside: view the Pleiades or M13 with binoculars, and follow ESA/NASA data releases to see how Gaia and Hubble continue to refine these stories.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.