The Carrington Event of 1859 showed how suddenly space weather can hit home: telegraph systems around the world sparked and operators received shocks when a powerful solar storm slammed Earth’s magnetosphere on September 1–2, 1859. That episode was a dramatic, 19th-century wake-up call that energetic particles and high-energy photons from the Sun can disrupt technology and alter upper atmospheres. Across the solar system and far beyond, nature builds radiation environments from fast protons to gamma rays and from trapped belts to extreme magnetic fields. These zones matter for spacecraft design, astronaut safety, planetary habitability, and fundamental physics—because some of them can literally fry electronics, change atmospheres, or test the limits of known physics.

Below are ten of the most consequential high-energy environments you might encounter when exploring space, grouped into four categories: solar/heliospheric sources; planetary magnetospheres and belts; compact objects; and cosmic/interstellar events. Each entry explains why the environment is dangerous, gives concrete historical or observational examples, and notes how scientists and mission planners respond. A strong solar storm today could still disrupt satellites and power grids, so these aren’t just abstract curiosities.

Solar and Heliospheric Sources

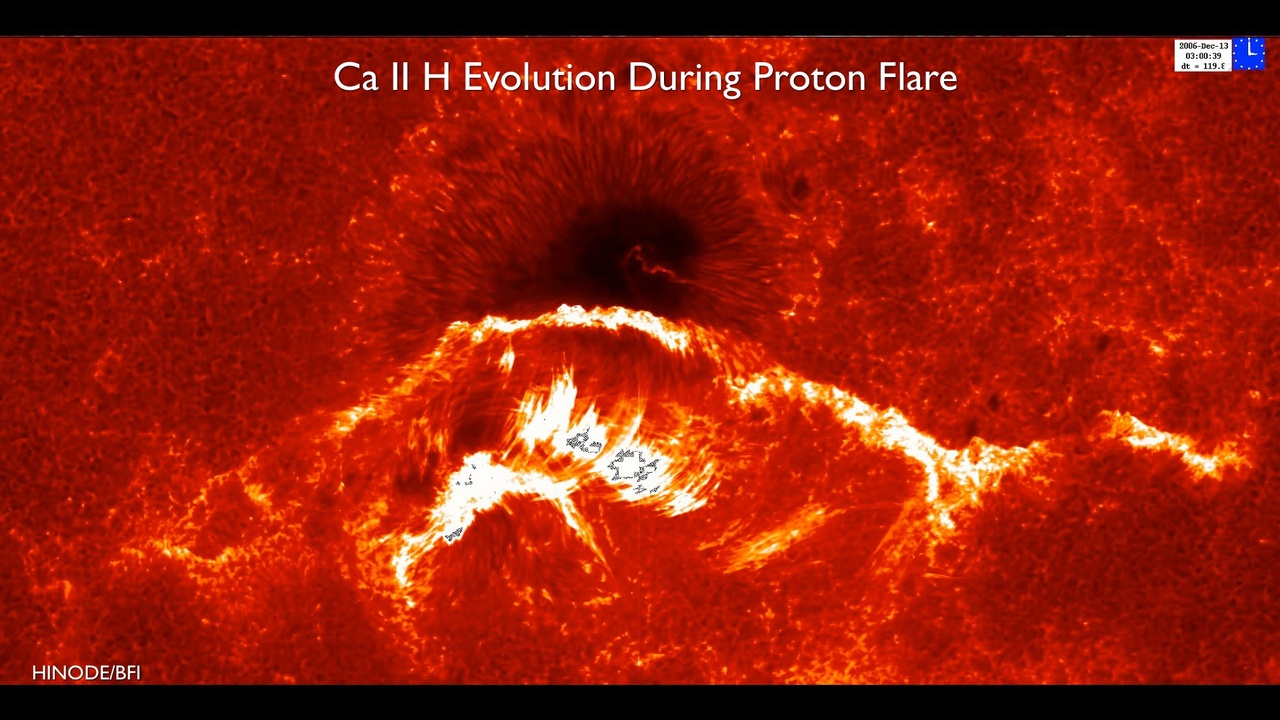

The Sun is our nearest and most immediate source of energetic photons and particles. Solar flares produce intense X-ray and extreme-UV bursts, while coronal mass ejections (CMEs) launch billions of tons of magnetized plasma that drive shocks and accelerate particles into the inner solar system. Together they create short, sharp electromagnetic spikes and longer-duration particle storms that reach Earth in minutes to days and can produce some of the most intense radiation in space for human technology.

1. Solar Flares and Coronal Mass Ejections

Solar flares are rapid releases of magnetic energy on the Sun that show up as X-ray and EUV bursts; CMEs are expulsions of plasma that drive shocks and accelerate particles. The Carrington Event (1859) combined intense visible aurora and telegraph failures with a massive geomagnetic disturbance. In October 1989 a CME-driven geomagnetic storm triggered the Quebec power blackout on March 13, 1989, and the late October–November 2003 “Halloween storms” elevated satellite radiation levels, disrupted GPS, and forced some airlines to change polar routes.

Flares produce immediate X-ray and gamma-ray spikes while CME shocks create solar energetic particle streams that can raise dose rates for hours to days after arrival. Operators respond by placing satellites into safe modes, delaying launches, and rerouting high-latitude flights. Space agencies use hardened electronics, redundancy, and procedures to protect crews and instruments during these episodes.

2. Solar Energetic Particle (SEP) Events

SEPs are fast streams of protons and heavier ions accelerated by flares and CME-driven shocks, with energies ranging from a few keV up to the GeV scale. High-end SEP particles can penetrate significant shielding and deliver dangerous ionizing doses to unshielded electronics and astronauts.

Major SEP episodes in the 2003 Halloween storms produced large fluxes lasting days, and instruments aboard satellites recorded event-integrated fluences that required operators to change mission plans. NASA and ESA now incorporate SEP forecasting (NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center issues alerts) and design crewed vehicles with storm shelters and additional shielding concepts for planned missions like Artemis. Mission planners schedule EVAs to avoid predicted SEP windows and include extra monitoring for rapid-onset events.

Planetary Magnetospheres and Radiation Belts

Planetary magnetic fields trap charged particles, forming persistent radiation belts that can subject orbiters and nearby moons to continuous high-energy fluxes. Earth’s discovery of these belts in 1958 provided the first clear picture of a trapped-particle environment, but Jupiter’s belts are far harsher—orders of magnitude stronger—and require special engineering for any mission that ventures into the Jovian system.

3. Jupiter’s Radiation Belts

Jupiter hosts some of the most intense steady-state particle fluxes in the solar system. Electrons and ions trapped in Jupiter’s magnetic field reach fluxes many orders of magnitude higher than Earth’s Van Allen belts, and radiation doses near the planet are high enough to cripple unshielded electronics over short mission durations.

The Galileo mission (arrived 1995; operations through 2003) experienced repeated radiation-induced glitches and required robust fault protection and shielding design. Current missions such as Europa Clipper (planned for the mid-2020s) and ESA’s JUICE plan trajectories and instrument duty cycles to limit exposure, using radiation-tolerant components and orbit strategies that reduce time spent in the worst zones.

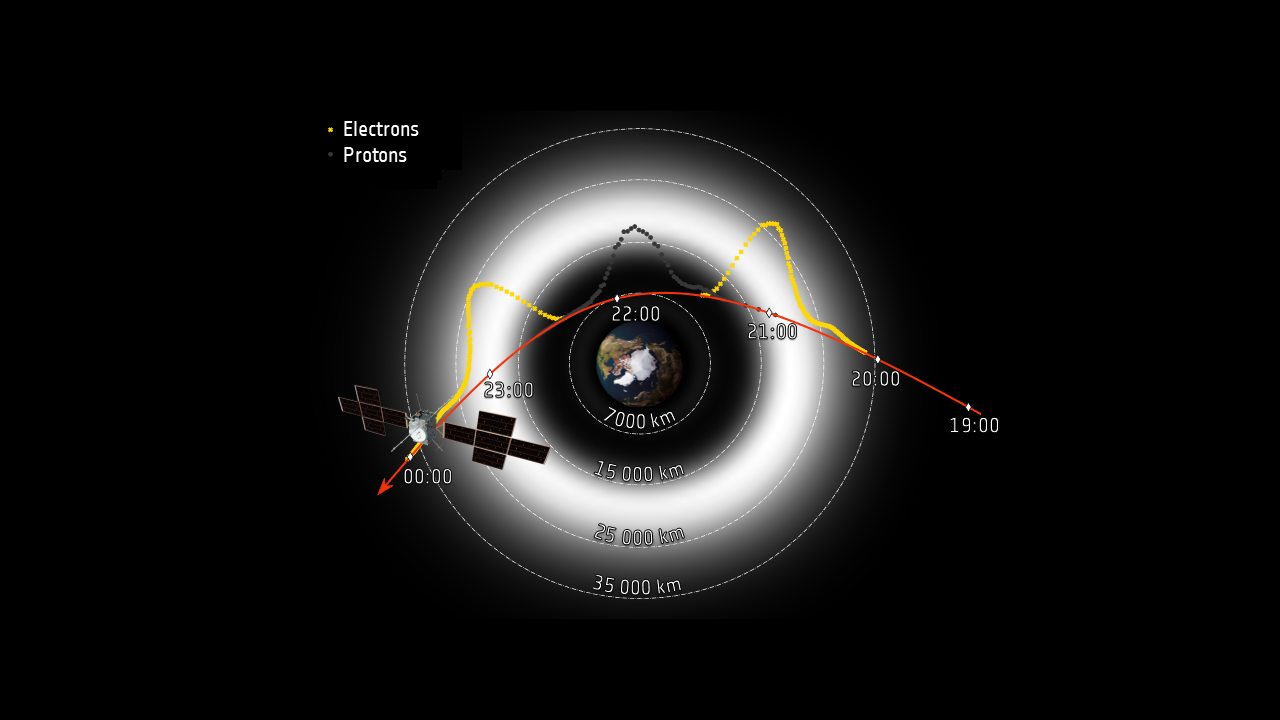

4. Earth’s Van Allen Belts

Earth’s Van Allen belts were discovered after Explorer 1 and Explorer 3 in 1958 and remain the best-studied radiation belts. There are two broad regions: an inner belt dominated by energetic protons and an outer belt controlled largely by energetic electrons.

The belts extend roughly from 1,000 km above Earth to tens of thousands of kilometers (and vary with solar activity). NASA’s Van Allen Probes (launched in 2012) refined our picture of belt dynamics and revealed temporary “killer electron” populations that can damage satellites. Operators plan transfer orbits, safe modes, and component selection with belt crossings in mind, especially for geostationary transfer and medium Earth orbits.

5. Radiation Near Volcanically Active Io and Other Moons

Moons embedded in strong magnetospheres face compounded hazards: trapped-particle flux from the parent planet plus local plasma produced by volcanic or atmospheric activity. Io is a prime example—the moon injects material into Jupiter’s magnetosphere, creating the Io plasma torus and boosting local particle densities and energies.

Galileo performed dozens of Io flybys in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and radiation limits constrained how close and how long the spacecraft could approach the moon. Any future Io lander would have to tolerate high dose rates; mission lifetimes and instrument choices must account for that harsh local environment.

Compact Objects: Pulsars, Magnetars, and Black Holes

Compact objects—neutron stars and black holes—produce some of the highest-energy electromagnetic radiation known. From short, catastrophic magnetar flares to steady pulsar beams and the broadband emission from accreting black holes and their jets, these sources illuminate extreme physics: relativistic plasmas, ultra-strong magnetic fields, and particle acceleration to very high energies.

Astrophysicists study these environments both to understand fundamental processes and to test theories that can’t be replicated on Earth. Observatories like Chandra, XMM-Newton, Fermi LAT, and ground-based Cherenkov arrays have cataloged many bright sources and transients.

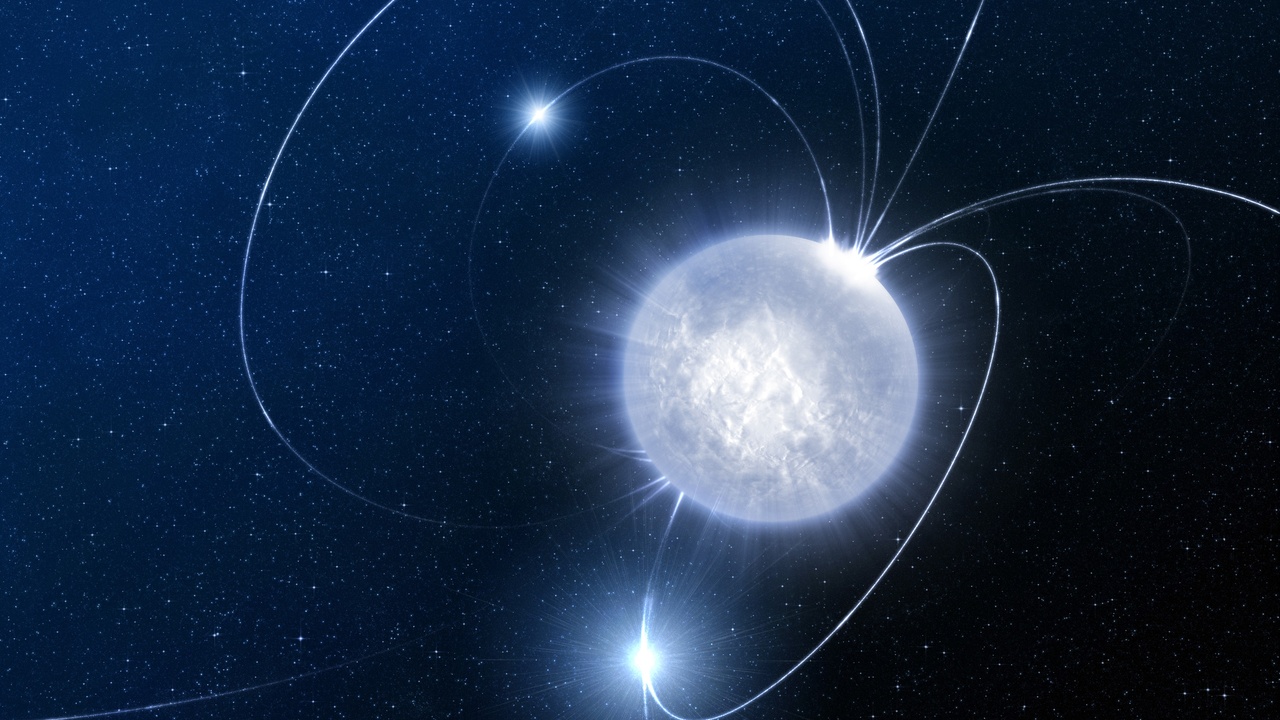

6. Magnetar Giant Flares

Magnetars are neutron stars with surface magnetic fields around 10^14–10^15 gauss. Their magnetic stresses occasionally rearrange catastrophically, producing giant gamma-ray flares that, for a brief moment, can outshine the rest of the galaxy in high-energy photons.

The giant flare from SGR 1806-20 on December 27, 2004, is a textbook example: spacecraft worldwide detected intense gamma-ray fluxes, and the event produced measurable disturbances in Earth’s ionosphere despite the source being tens of thousands of light-years away. Such flares are rare but provide unique tests of physics in ultra-strong magnetic fields and probes of quantum electrodynamics in regimes we can’t recreate in labs.

7. Young Pulsars and Their Nebulae

Young pulsars, like the Crab Pulsar, spin rapidly and emit pulsed high-energy radiation driven by their strong magnetic fields and rotation. The Crab Pulsar rotates about every 33 milliseconds and powers the surrounding Crab Nebula, which shines across radio to gamma rays.

Observations in the 2010s recorded brief gamma-ray flares from the Crab Nebula, showing that even apparently steady nebulae can accelerate particles to extreme energies. Pulsars and their nebulae are natural particle accelerators that help us understand cosmic-ray production and magnetic reconnection in relativistic plasmas.

8. Accretion Disks and Relativistic Jets Around Black Holes

Accretion onto black holes heats gas to millions of kelvin, producing bright X-ray emission from hot coronae and launching relativistic jets that emit from radio through TeV gamma rays. Microquasars—stellar-mass black holes in binary systems—act as compact analogs of active galactic nuclei (AGN).

Ground-based Cherenkov telescopes and instruments like Fermi LAT detect photons up to TeV energies from jets, showing particle acceleration to extreme energies. Studies of these systems inform models of jet formation, particle acceleration, and energy budgets in astrophysical plasmas.

Cosmic and Interstellar High-Energy Events

On cosmic scales, transient events can release more energy in seconds than the Sun emits in billions of years. Gamma-ray bursts and ultra-high-energy cosmic rays represent extremes in instantaneous power and particle energy, respectively, and they shape our understanding of particle acceleration and possible impacts on planetary atmospheres over geological timescales.

9. Gamma-Ray Bursts (GRBs)

GRBs are brief explosions—lasting milliseconds to minutes—that emit enormous gamma-ray fluxes as relativistic jets pierce stellar envelopes or emerge from compact mergers. Satellites such as Swift and Fermi routinely detect GRBs across cosmic distances; a single burst can briefly outshine its host galaxy.

The multimessenger event GW170817/GRB 170817A in 2017 linked a short GRB to a neutron-star merger and provided direct evidence that such mergers produce at least some short GRBs. While a nearby GRB within a few thousand light-years could affect a planet’s atmosphere, such close events are rare on human timescales. Still, GRBs remain crucial probes of jet physics, nucleosynthesis, and relativistic outflows.

10. Galactic and Extragalactic Cosmic Rays (Ultra-High-Energy Cosmic Rays)

Cosmic rays are charged particles that reach Earth from space; the ultra-high-energy subset (UHECRs) carries energies above 10^18 eV per particle, making each one far more energetic than typical solar particles. They’re rare but incredibly penetrating, and their origins—supernova remnants, AGN, or exotic sources—remain an active research area.

Observatories such as the Pierre Auger Observatory and Telescope Array measure arrival directions and energies to study acceleration mechanisms. Cosmic-ray showers alter atmospheric chemistry locally and trigger ground-based detectors; understanding their sources informs both astrophysics and assessments of high-energy particle exposure beyond Earth’s protective layers.

Summary

- Historical storms matter: the Carrington Event (1859) and later storms (1989, 2003) show real-world vulnerability of grids, satellites, and polar aviation to intense solar-driven radiation.

- Local belts vs. cosmic extremes: Jupiter’s radiation belts are far harsher than Earth’s Van Allen belts, while magnetars and GRBs produce brief but extraordinarily powerful photon bursts.

- Practical implications: mission design, shielding, trajectory choices, and operational procedures (satellite safing, SEP shelters, EVA scheduling) are essential to manage intense radiation in space and to protect crews and hardware.

- Science payoff: studying these environments—from UHECRs above 10^18 eV to magnetar flares—advances fundamental physics, informs planetary habitability assessments, and improves forecasting that keeps satellites and people safe.

- Stay informed: follow space weather alerts and support radiation-hardened mission planning for upcoming programs (Europa Clipper, JUICE, Artemis) to reduce risk from the most intense radiation in space.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.