In 1995 astronomers announced 51 Pegasi b, the first hot Jupiter found orbiting a Sun-like star — a discovery that upended textbook ideas about planetary systems and set off a rush of follow-up studies.

That single detection proved planets beyond the Solar System weren’t rare curiosities but a diverse population waiting to be mapped. Today there are roughly 5,000 confirmed exoplanets (and counting), found by methods like radial velocity, transits, and timing, and characterized with tools from ground-based spectrographs to space observatories.

This piece profiles ten standout worlds chosen for scientific interest, extremes, habitability potential, and historical significance — not a strict ranking. You’ll read about blistering hot Jupiters, evaporating Neptunes, nearby rocky candidates, and exotic systems revealed by missions and instruments such as Kepler, TESS, Hubble, Spitzer, JWST, HARPS, VLT and Keck. This roundup looks at 10 of the most fascinating exoplanets and the observations that made them memorable.

Strange Worlds and Extremes

Planets at the extremes — the hottest, most distorted, or most irradiated — push physical theory to its limits and reveal processes that don’t operate in the Solar System. Spectroscopy, phase-curve photometry and secondary-eclipse measurements let astronomers probe temperatures, winds, and composition on worlds heated to thousands of kelvin.

Among the most fascinating exoplanets in this class are hot Jupiters that orbit within a few stellar radii, objects whose atmospheres are stripped by ultraviolet light, and planets so close to Roche limit that tides distort their shape. Space telescopes (Hubble, Spitzer, JWST) combined with high-resolution ground instruments (VLT/CRIRES, Keck) have been crucial for detecting atomic metals, thermal emission and escaping gas.

Studying these extremes tests atmospheric chemistry and tidal physics, and helps refine migration and formation scenarios that explain how giant planets end up so near their stars.

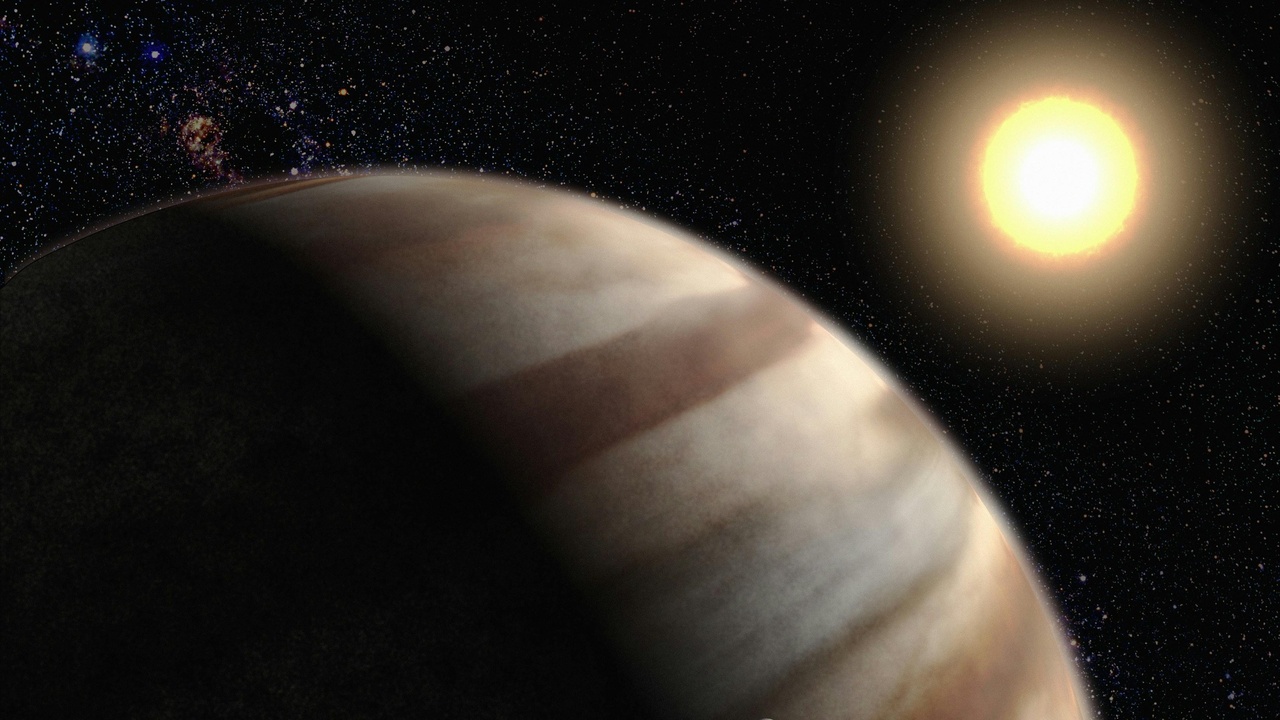

1. 51 Pegasi b — The hot Jupiter that rewrote the rules (1995)

51 Pegasi b was the first hot Jupiter discovered around a Sun-like star, announced in 1995 by Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz using the radial-velocity method; its 4.2-day orbit surprised theorists who expected giant planets only at large separations. The planet’s minimum mass is about 0.46 Jupiter masses and the tight orbit required migration or dynamical histories to explain its present location.

The discovery forced a rethink of planet-formation models and spurred intensive radial-velocity and transit searches for close-in planets. Mayor and Queloz’s work later earned them the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics, and the case of 51 Pegasi b still shapes how we model giant-planet migration and tidal interactions today.

2. KELT-9b — The blistering world hotter than some stars (~4,600 K)

Discovered in 2017, KELT-9b orbits an A-type star about every 1.5 days and has a dayside temperature in the range ~4,000–4,600 K — comparable to a mid-K or even early-M star’s photosphere. Its mass is roughly 2.8 Jupiter masses, but the extreme irradiation means molecules dissociate and metal atoms exist in the gas phase.

High-resolution ground-based spectroscopy has detected atomic iron and titanium in the atmosphere, and strong UV flux drives rapid atmospheric escape. KELT-9b serves as a laboratory for high-temperature chemistry and for testing spectrographs designed to resolve narrow atomic lines under extreme conditions.

3. WASP-12b — The planet losing mass to its star (Roche-lobe overflow)

WASP-12b, found in 2008, orbits its host star every ~1.1 days and is highly inflated (radius ~1.9 RJ), so close that stellar tides pull material from the planet’s outer layers. Observations have revealed excess infrared emission and evidence for a comet-like tail indicative of mass loss and Roche-lobe overflow.

Hubble and Spitzer data showed near-UV absorption and thermal signatures consistent with escaping gas, and JWST follow-up has begun to measure the composition of the outflow. WASP-12b illustrates how extreme star–planet interactions determine lifetimes of close-in giants and how tidal heating can inflate planetary radii.

Potentially Habitable and Earth-like Candidates

Planets highlighted for potential liquid water or Earth-like conditions sit within the circumstellar habitable zone, where stellar radiation allows surface temperatures amenable to liquid water — but habitability depends on many factors beyond orbital distance. Atmosphere, planet size, composition and stellar activity all shape actual conditions.

These worlds attract intense follow-up with JWST and upcoming Extremely Large Telescopes (ELTs), which can probe atmospheres via transit and emission spectroscopy. Proximity to Earth, host-star type, and system architecture determine whether a target yields conclusive atmospheric constraints.

We profile Kepler-186f, the TRAPPIST-1 system’s temperate world TRAPPIST-1e, and Proxima Centauri b — three planets that pushed searches for nearby habitable candidates and shaped mission planning for atmospheric characterization.

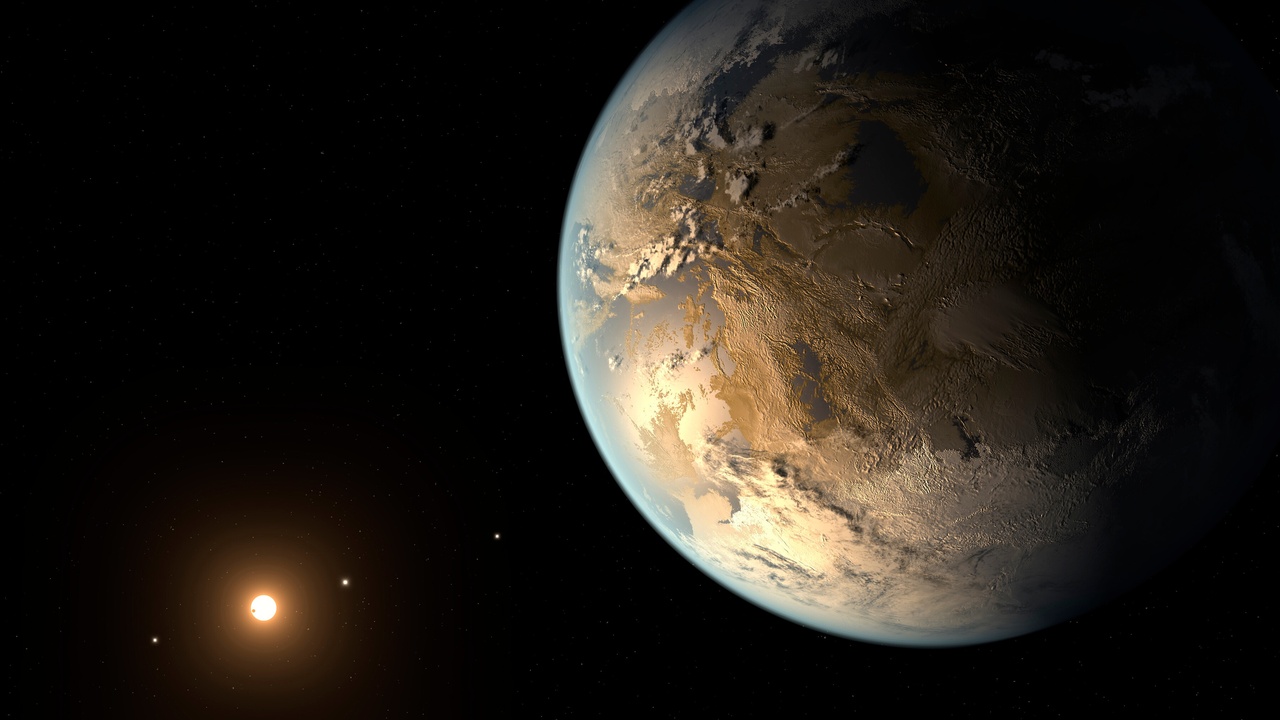

4. Kepler-186f — First Earth-size planet in a star’s habitable zone (2014)

Kepler-186f, announced in 2014 from Kepler transit data, was the first Earth-size planet found in the habitable zone of another star. Its radius is about 1.1 Earth radii, and it orbits an M-dwarf roughly 500 light-years away, with an orbital period near 130 days.

Mass and atmosphere remain unconstrained, so whether it’s rocky or holds liquid water is unknown. Still, Kepler-186f proved Earth-size HZ planets exist and helped refine occurrence-rate estimates (η⊕) that guide the design of future direct-imaging missions and large surveys.

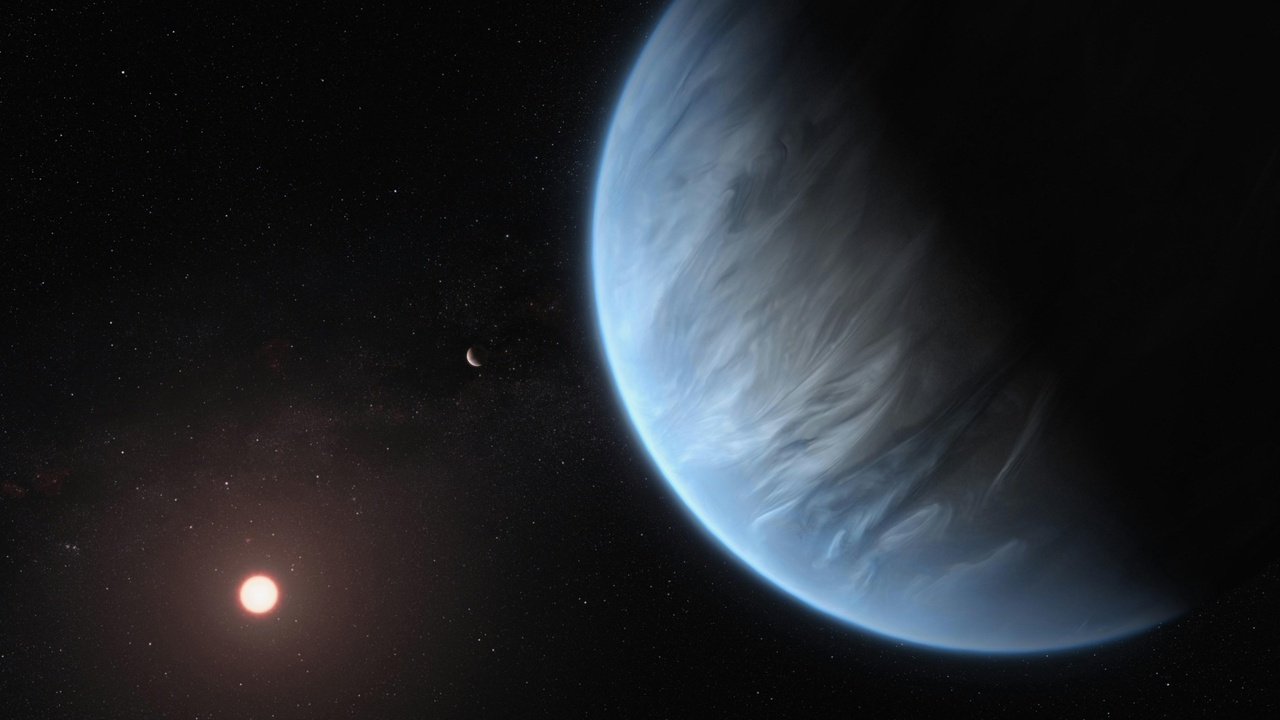

5. TRAPPIST-1e — One of several Earth-size worlds in a single compact system (2017)

The TRAPPIST-1 system (discovered via ground-based TRAPPIST telescopes and confirmed with Spitzer) hosts seven roughly Earth-size planets in a compact configuration about 39 light-years away, announced between 2016 and 2017. TRAPPIST-1e sits near the system’s temperate zone and has a radius close to Earth’s (≈0.9–1.1 R⊕).

A key advantage is comparative planetology: multiple temperate, similar-size bodies around one star let astronomers compare atmospheres under the same stellar irradiance and formation history. Hubble and JWST spectroscopy programs are targeting TRAPPIST-1 planets to search for atmospheres and potential water signatures.

6. Proxima Centauri b — Our nearest potentially habitable neighbor (2016)

Proxima Centauri b was detected by radial velocity with HARPS and announced in 2016; it orbits the nearest star to the Sun at ~4.24 light-years. The planet has a minimum mass near 1.3 Earth masses and an orbital period of ~11.2 days, placing it within the star’s temperate zone.

Challenges for habitability include strong stellar flares from this active M-dwarf and likely tidal locking; such activity could erode atmospheres without a strong magnetic field or thick envelope. Its proximity makes it the highest-priority target for future direct imaging and for conceptual missions like Breakthrough Starshot and for long-term monitoring with ELTs.

Odd Compositions and Unusual Orbits

Some planets defy Solar System analogs via strange bulk compositions or eccentric, misaligned orbits. A handful of discoveries hint at carbon-rich interiors, iron-dominated super-Earths, or planets actively losing mass and forming comet-like tails.

These cases broaden the taxonomy of planets and constrain formation pathways: whether a planet forms in-situ, migrates, or suffers giant impacts can leave imprints on composition and orbit. Observations from Hubble (Lyman-alpha), Spitzer, and ground-based spectrographs inform models of photoevaporation and interior chemistry.

7. Gliese 436 b — A Neptune-like planet with a comet-like tail

Gliese 436 b, discovered in 2004, is a Neptune-class planet (~22 Earth masses) that revealed unexpected signs of atmospheric escape. Hubble Lyman-alpha observations detected an extended cloud of neutral hydrogen trailing the planet, producing deeper and variable transits in ultraviolet than in visible light.

This escaping envelope is interpreted as photoevaporation driven by stellar radiation, and it provides a live example of how close-in Neptunes can lose atmospheres and potentially become smaller, rocky cores. Comparing Gliese 436 b with populations identified by Kepler and TESS helps validate photoevaporation models across different stellar types and ages.

8. 55 Cancri e — A super-Earth with hints of exotic interior chemistry

55 Cancri e orbits its star every ~0.74 days and has a super-Earth mass near 8 M⊕ with a radius around 1.9 R⊕ (values vary with improved measurements). Initially, bulk-density models suggested an unusually carbon-rich interior, leading to speculative nicknames like “diamond planet,” but later atmospheric and thermal-emission data complicated that picture.

Spitzer detected thermal emission and variability from the planet’s dayside, while follow-up spectroscopy with Hubble and ground facilities has yet to yield a simple composition. 55 Cancri e demonstrates the pitfalls of inferring interior chemistry from mass and radius alone and underscores the need for combined thermal and spectroscopic constraints.

Exotic Systems and Record-Breakers

Some system architectures rewrote expectations: planets orbiting pulsars proved detection techniques could spot tiny timing signals, while circumbinary planets showed disks can produce planets even in dynamically complex binaries. Record-holders — the first, nearest, most extreme — often steer how telescopes allocate follow-up time.

Discoveries like the pulsar planets and Kepler’s circumbinary detections expanded instrument pipelines and motivated new search strategies for timing, transits, and direct imaging. They remain touchstones for the diversity of planetary outcomes and for testing formation under unusual conditions.

9. PSR B1257+12 planets — The first confirmed exoplanets (1992)

The first confirmed exoplanets were announced in 1992 around the pulsar PSR B1257+12 by Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail, detected via periodic variations in radio-pulse arrival times. The planets range from lunar to roughly Earth masses, and their existence around a neutron star raised immediate questions about survival after a supernova or second-generation formation.

These pulsar-timing detections proved that precision timing methods could reveal tiny companions and showed planets can exist in extreme environments. The discovery predated the 1995 hot-Jupiter era and broadened the search for planets to include diverse stellar remnants and detection techniques.

10. Kepler-16b — A true circumbinary ‘Tatooine’ world

Kepler-16b, announced in 2011 from Kepler transit data, orbits two stars and produces transits across both stellar components — a real-world analogue of “Tatooine.” The planet is roughly Saturn-sized and occupies a stable circumbinary orbit, proving that planet formation and disk evolution can produce planets in binary-star environments.

Modeling Kepler-16b required careful treatment of transit timing and geometry, and the detection motivated searches for other circumbinary planets. Kepler’s sensitivity to complex transit signals demonstrated how novel analysis pipelines and long-baseline photometry can reveal unexpected system architectures.

Summary

- Exoplanets span a huge range — from ultra-hot Jupiters and evaporating Neptunes to nearby rocky candidates — expanding our view of possible worlds.

- Unusual discoveries (pulsar planets, circumbinary worlds, Roche-lobe overflow) test formation, migration and atmospheric-escape models and refine observational strategies.

- Current and upcoming observatories — JWST, ELTs, TESS follow-ups, Hubble archives and ground-based spectrographs (HARPS, VLT, Keck) — will deepen atmospheric and composition constraints and search for biosignatures.

- Readers can follow mission results and participate in citizen-science projects (e.g., Zooniverse/Planet Hunters) to stay engaged as new discoveries arrive.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.