A massive iron mass the size of a small car lies where it fell some 80,000 years ago — and people still travel to see it today. That rock is Hoba, roughly 60 tonnes of iron‑nickel sitting near Grootfontein in Namibia, and it offers a direct, tactile link to deep time. Meteorites like Hoba and the 2013 Chelyabinsk airburst (15 February 2013) matter because they deliver preserved material from other worlds, inform scientific timelines, and sometimes change communities’ lives.

There are thousands of finds and falls, but a relatively small group shaped science, law, and public awareness. This piece profiles 10 of the most famous meteorites, highlighting dates, weights, key discoveries, cultural stories, and where you can see fragments today.

Historic discoveries and early finds

Long before laboratories catalogued meteorite types, farmers, indigenous people, and explorers encountered strange, heavy stones and iron masses on the landscape. Chance discoveries often created local landmarks, stirred legends, and eventually attracted scientists and museums. Some finds were so large they stayed put and became tourist draws; others entered legal debates about ownership and repatriation.

1. Hoba — the largest intact meteorite

Hoba is the largest known intact meteorite, with an estimated mass of roughly 60 tonnes. Farmers uncovered it in 1920 on a Namibian farm near Grootfontein, and analysis shows it’s mostly iron‑nickel. Because moving the mass would have been impractical, authorities preserved it in place, creating an on‑site protected area that draws visitors from around the world.

The meteorite’s immobility turned it into a national landmark and an educational exhibit, with local tourism supporting the town economy. Visitors can walk right up to the slab and see natural fusion crust and regmaglypts on its weathered surface.

2. Willamette (Tomanowos) — cultural and legal significance

The Willamette meteorite, found in Oregon around 1902 and often called Tomanowos by local Native American groups, carries deep cultural meaning. After discovery, the stone entered museum circulation and was displayed at institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, which sparked long‑running discussions about stewardship and cultural rights.

Willamette prompted museums to rethink how they handle culturally sensitive objects and to negotiate with tribal groups over display, access, and interpretation. Its story illustrates how a single rock can sit at the intersection of science, law, and indigenous heritage.

3. Campo del Cielo — a historic Argentine crater field

Campo del Cielo is a scattered iron meteorite field in northern Argentina known to Europeans since roughly 1576, when Spanish colonists recorded indigenous knowledge of iron masses. The impact area covers about 18 km across, and dozens of fragments and several craters were documented by early explorers and later scientific teams.

Local communities historically recovered pieces for practical use, and modern surveys recovered many large fragments that now appear in Argentine and international museum exhibits. Campo del Cielo remains an active site for researchers mapping fragmentation patterns and for visitors examining impact geology up close.

Meteorites that reshaped planetary science

Certain falls and finds act like time capsules, preserving the solar system’s earliest solids or recording water‑rock interaction on other worlds. Carbonaceous chondrites and Martian meteorites have yielded pre‑solar grains, amino acids, and crustal material dated to about 4.56 billion years, informing models of planet formation and habitability. Below are three standout samples.

4. Allende — a window into the solar system’s first solids

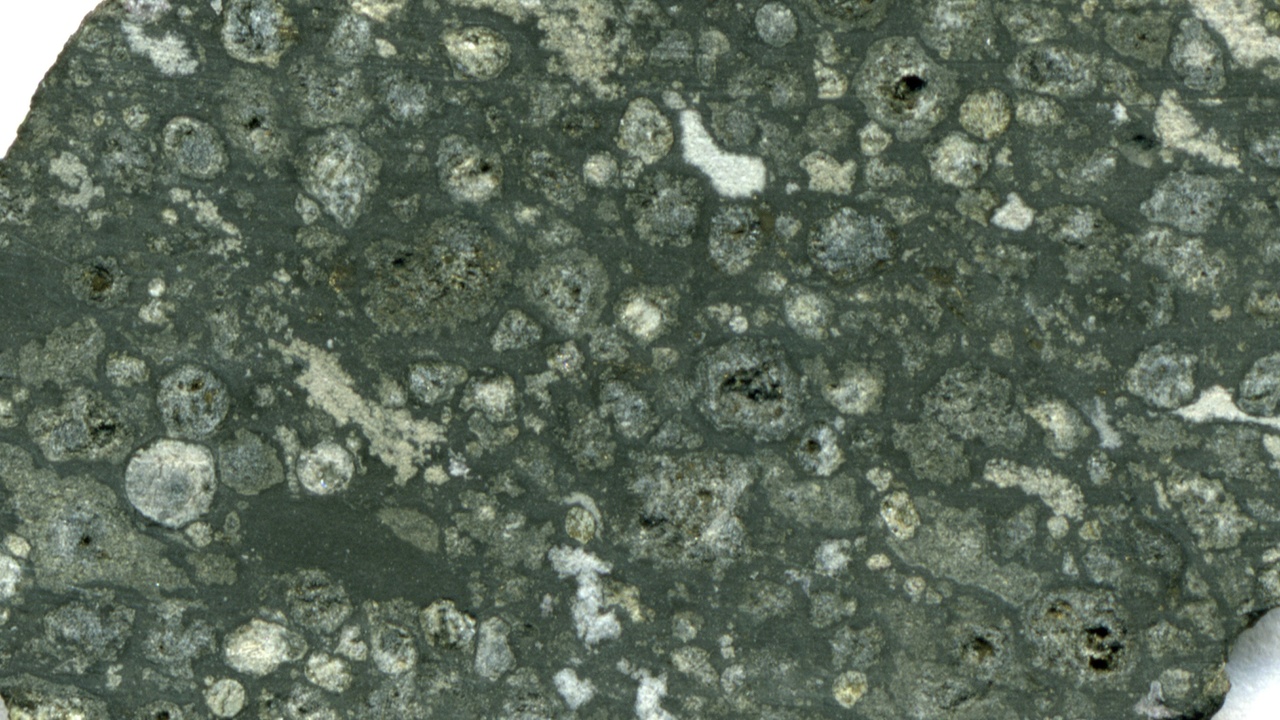

Allende fell over Chihuahua, Mexico, in 1969 and showered the countryside with many fragments that researchers quickly collected. It’s a carbonaceous chondrite notable for calcium–aluminum‑rich inclusions (CAIs) that have been dated to about 4.567 billion years — some of the oldest solids we can measure.

Because so many fragments were recovered after the 1969 fall, labs worldwide (including university isotope geochemistry groups) have studied Allende’s components to calibrate the solar system timeline. CAIs from Allende remain reference materials in cosmochemistry and continue to refine models of early nebular processes.

5. Murchison — rich in organic molecules

The Murchison meteorite fell near Murchison, Victoria, Australia, in 1969 and quickly became famous for its chemistry. Scientists found a large diversity of organic molecules, including dozens of amino acids (some studies report 70+ distinct types), plus complex organics that hint at prebiotic chemistry in space.

Murchison helped shift thinking about how organic matter could arrive on the early Earth and supply building blocks for life. Laboratories from multiple countries have analyzed its organics, isotopes, and mineralogy to understand synthesis pathways in the early solar system.

6. NWA 7034 (Black Beauty) — a Martian puzzle piece

NWA 7034, nicknamed “Black Beauty,” was found in Northwest Africa and entered collections around 2011. Unlike typical SNC meteorites, it’s a brecciated Martian regolith sample containing ancient crustal clasts and water‑related minerals that record Mars’ early crustal history.

Analyses of Black Beauty’s age range and alteration minerals have helped researchers refine timelines for Martian crust formation and alteration, and they inform rover and orbiter mission planning by linking returned meteoritic chemistry to orbital observations.

Dramatic witnessed falls and public impact

When people actually see a meteor fall—sometimes on video—the event becomes part of public memory. Witnessed falls provide precise context (time, trajectory, sonic effects) and often yield fresh, uncontaminated samples. Some events caused injuries or damage, prompting improvements to monitoring networks and emergency planning.

7. Chelyabinsk — a modern airburst that shook a city

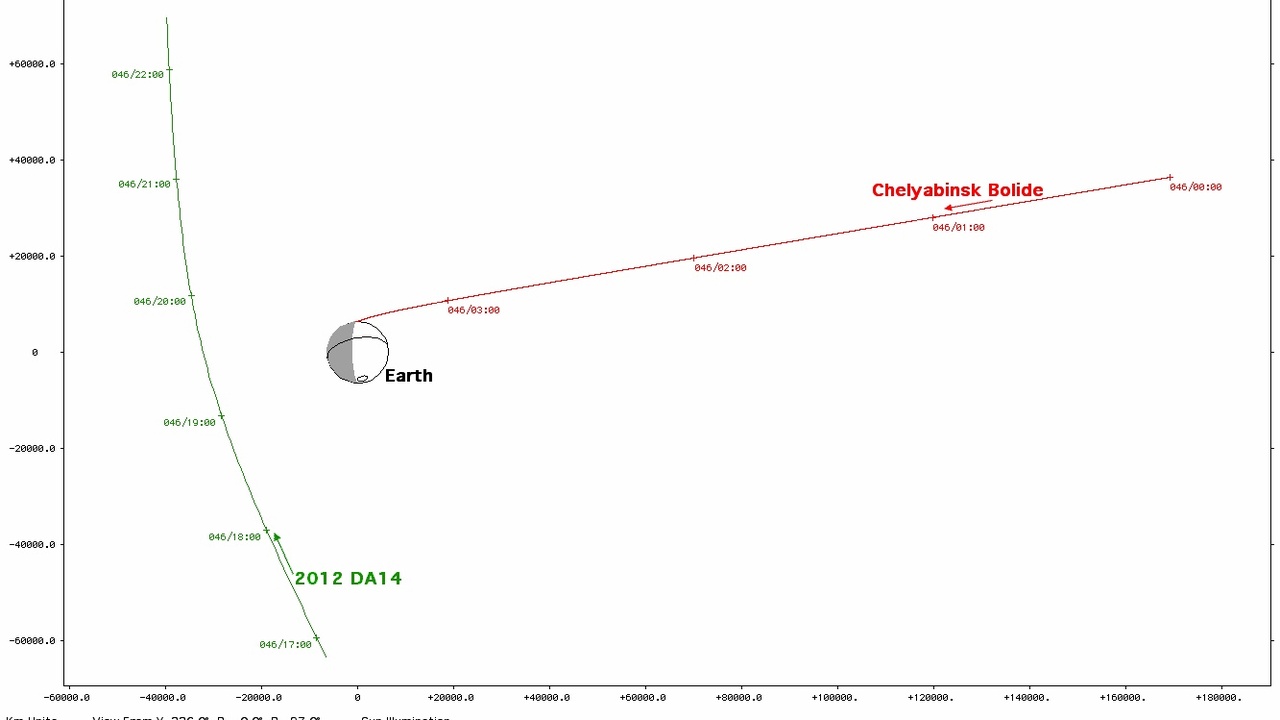

On 15 February 2013 a roughly 20‑meter object exploded over Chelyabinsk, Russia, producing a powerful shockwave that shattered windows and injured about 1,500 people (mostly from broken glass). The event was captured on hundreds of dashboard and security cameras, providing unprecedented observational data.

Chelyabinsk focused global attention on near‑Earth object monitoring. Scientists recovered fragments from Lake Chebarkul and surrounding areas, and agencies worldwide used the event to expand detection efforts and public preparedness for airburst hazards.

8. Sikhote‑Alin — a spectacular iron shower in 1947

Sikhote‑Alin fell in February 1947 in the Sikhote‑Alin mountains of eastern Russia as a bright fireball that broke into thousands of iron fragments. Observers recorded a dramatic shower of shrapnel, and teams later recovered many masses, including individual pieces weighing hundreds of kilograms.

Because the fragments were so fresh, researchers studied their craterlets, fragmentation patterns, and shock textures to better understand how large iron meteoroids break apart in the atmosphere. Sikhote‑Alin specimens now appear in museums and collections worldwide.

Treasures for collectors and museums

Some meteorites become prized objects because they’re rare, visually striking, or historically important. Pallasites show translucent olivine crystals set in metal, while massive iron meteorites make dramatic displays. Collectors and museums value those traits, but legal and ethical collecting practices also shape what enters the market.

9. Fukang — a gem among meteorites (pallasite)

Fukang, found near the city of Fukang in China around 2000, is a celebrated pallasite notable for large, gem‑quality olivine (forsterite) crystals embedded in a metallic matrix. Polished slices reveal translucent green‑yellow crystals that sparkle under lighting, making them ideal for museum cases and educational displays.

Collectors prize Fukang slices; museums use thin sections and polished faces to teach about metal‑silicate mixing and planetary differentiation. Typical display slices range from a few centimeters across up to much larger museum specimens that showcase the olivine crystals.

10. Cape York (Ahnighito) — a cultural and museum giant

Cape York meteorites, including the massive Ahnighito, provided iron for Inuit communities before European contact. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries explorers removed several large masses for transport to museums; Ahnighito alone is roughly on the order of 30 tonnes and remains a major display piece.

Those huge iron masses shaped toolmaking traditions and later became museum centerpieces, such as the impressive iron displays at the American Museum of Natural History. The history raises questions about removal, cultural heritage, and how museums interpret such objects today.

Summary

Across science, culture, hazard awareness, and collecting, a handful of stones stand out. From Hoba’s iron slab and Cape York’s cultural legacy to Allende and Murchison’s chemical records and Chelyabinsk’s wake‑up call, these specimens changed how we think about planetary origins and public safety.

- Meteorites connect us to planetary origins, local history, and public safety.

- Some specimens (Allende, Murchison, NWA 7034) advanced scientific knowledge about early solids, organics, and Martian crust.

- Witnessed falls like Chelyabinsk and Sikhote‑Alin prompted better monitoring, recovery efforts, and public preparedness.

- Large and beautiful pieces (Hoba, Fukang, Cape York) preserve cultural stories and remain major museum attractions.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.