Medieval chroniclers blinked at a sudden, brilliant star that turned day into a dim twilight: SN 1006 and SN 1054 were so bright people could read by their light and wrote them into seaside logs, monastery annals and court records. Those eyewitness accounts—often terse but consistent—are the human link to cradles of gas and shock fronts we study with radio dishes and X-ray telescopes today.

These are the most catastrophic supernovas that astronomers have tied to specific remnants, events that forged heavy elements, sent neutrinos through Earth, and forced philosophers and scientists to rethink the heavens. They range from the earliest recorded burst in 185 CE to modern, instrumented explosions like SN 1987A that produced detectable neutrinos on Earth.

Historic naked-eye explosions

Before telescopes, bright supernovas announced themselves to the naked eye and to record-keeping cultures across Asia, the Middle East and Europe. Written observations let modern astronomers match those “guest stars” to remnants like the Crab Nebula or RCW 86, and those matches have cultural and scientific weight: they helped topple ideas of an immutable sky and provided timestamps for long-lived shock structures we study in X-rays and radio.

Historical records also supply concrete numbers—years, months visible, and occasionally position—that help calibrate supernova rates and the ages of remnants we image with modern observatories.

1. SN 185 — The earliest recorded supernova

Chinese court astronomers recorded a “guest star” in 185 CE that stayed visible for several months, a record widely regarded as the earliest well-documented supernova observation. The modern candidate linked to that event is RCW 86, a shell-like remnant bright in X-rays and radio.

RCW 86’s age, its shock-heated X-ray spectrum, and the historical date align well, making SN 185 invaluable: it’s a rare nearby explosion whose remnant still teaches us about long-term shock evolution and the lifetime of supernova debris.

2. SN 1006 — The brightest stellar explosion recorded

Observed across Asia and Europe in 1006 CE, SN 1006 is widely regarded as the brightest supernova recorded by humans, with historical accounts implying a peak brightness comparable to a thin crescent moon. Modern estimates put its peak apparent magnitude around −7 to −8 and place the remnant at roughly 7,000–7,200 light-years (remnant designation G327.6+14.6).

Accounts from Arabic, Chinese and European observers all describe an object visible during daytime for weeks, giving astronomers a rare cross-cultural dataset to compare with the expanding shell and synchrotron emission we now image in radio and X-rays.

3. SN 1054 — The explosion that created the Crab Nebula

Recorded in 1054 CE, SN 1054 produced the Crab Nebula (Messier 1), one of astronomy’s best-studied remnants. The nebula contains a central pulsar—a fast-rotating neutron star—whose regular pulses and wind power a bright synchrotron nebula across radio, optical and gamma rays.

The link between an observed naked-eye explosion (year 1054), a persistent nebula, and a neutron star gave a direct observational chain from stellar core collapse to compact-object formation and energized nebula, a milestone for understanding how massive stars end their lives.

Early modern witnesses and remnants

The Renaissance and early modern era gave us named observers and painstaking records: Tycho Brahe mapped a “new star” in 1572, and Kepler took detailed notes on the 1604 event. Those observations challenged Aristotelian immutability and helped build precision observational astronomy.

Modern spectroscopy and imaging tie those accounts to physical classifications—Type Ia for Tycho and debated subtypes for Kepler—so these historic bursts became laboratories for nucleosynthesis, distance calibration and shock physics.

4. SN 1572 (Tycho) — A Type Ia that reshaped astronomy

In 1572 Tycho Brahe recorded a bright new star visible for months that contradicted the idea of an unchanging cosmos. Centuries later, spectral and light-curve work identifies SN 1572 as a Type Ia supernova.

Tycho’s event (year 1572) is scientifically important because Type Ia explosions serve as standardizable candles—objects later used to measure cosmic distances and, ultimately, cosmic acceleration. The remnant’s composition and expansion remain valuable for studies of white-dwarf explosions and binary progenitors.

5. SN 1604 (Kepler) — The last naked-eye supernova of the Milky Way

Johannes Kepler published observations of the 1604 “new star,” generally regarded as the most recent Milky Way supernova seen without telescopes. It shone across Europe in 1604 and left a remnant that we now study in X-rays and optical emission lines.

Although its subtype has been debated (Type Ia versus a more complex interacting variety), Kepler’s supernova provides a nearby case for shock interaction and for tying light-curve behavior to remnant structure imaged by observatories like Chandra.

Nearby modern supernovas that advanced science

In the era of CCDs, neutrino detectors and space telescopes, a handful of nearby supernovas gave unprecedented, direct tests of theory. They yielded neutrinos, allowed progenitor-star imaging and supplied dense multiwavelength datasets that changed how we model explosions.

Observatories from Kamiokande II to Hubble and Chandra each played roles; together they turned single events into decades-long experiments on core collapse, binary interaction and explosion asymmetry.

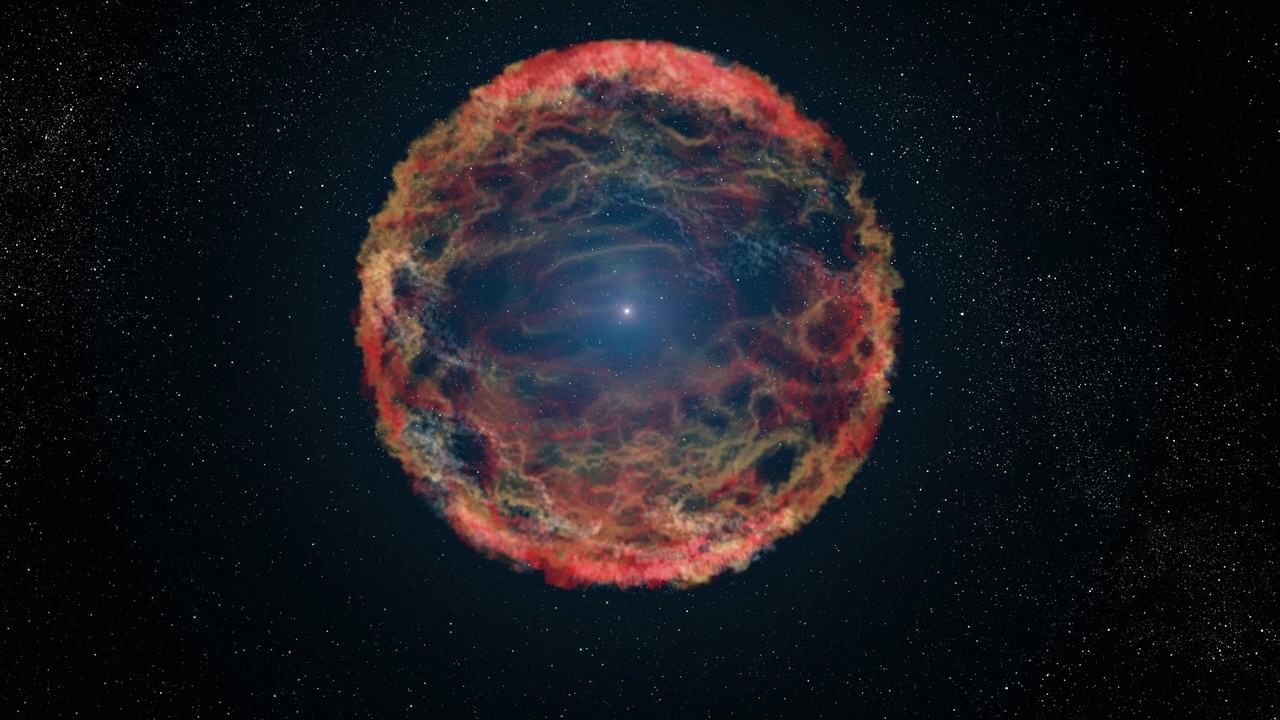

6. SN 1987A — Neutrinos and a nearby laboratory

SN 1987A exploded on 23 February 1987 in the Large Magellanic Cloud, about 168,000 light-years away, and it was close enough that underground detectors recorded the core-collapse neutrino burst. Kamiokande II, IMB and other facilities together saw roughly two dozen neutrinos over a few seconds—a direct confirmation of theoretical predictions for core collapse.

The supernova’s evolving light curve, the triple ring system imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope, and long-term X-ray monitoring of the shock interaction have made SN 1987A a touchstone for models of massive-star death and remnant evolution.

7. SN 1993J — A nearby, well-observed Type IIb

Discovered in March 1993 in the galaxy M81 (distance ~11 million light-years), SN 1993J showed a rapid spectral transition from hydrogen-rich to hydrogen-poor lines, making it a textbook Type IIb. That behavior pointed to a star that had lost much of its hydrogen envelope before exploding—likely via mass transfer to a binary companion.

Because it was nearby and bright at early times, SN 1993J received dense spectroscopic, photometric and radio follow-up that clarified how binary stripping produces partial-envelope explosions and what that means for progenitor populations.

8. SN 2014J — A nearby Type Ia that tested cosmology tools

SN 2014J appeared in January 2014 in M82, roughly 11–12 million light-years away, and became one of the closest Type Ia explosions in decades. That proximity allowed high-cadence photometry and spectroscopy that constrained extinction, color evolution and light-curve shape—key systematics for using Type Ia supernovas as distance indicators in cosmology.

Careful Hubble and ground-based follow-up of SN 2014J helped refine calibration methods and reduce uncertainties that propagate into measurements of the Hubble constant and dark energy studies.

Extremely energetic and unusual explosions

Some explosions outpace the familiar core-collapse or thermonuclear models: they peak far brighter, show signatures of extreme mass loss, or accompany relativistic jets and gamma-ray bursts. These exceptional cases expand the range of physics we must explain—from pair-instability mechanisms to jet-driven hypernovae.

They’re among the most catastrophic supernovas in terms of energy output and disruption, and they often force theorists to invent alternative channels for how massive stars die.

9. SN 2006gy — One of the most luminous explosions known

Discovered in 2006 in the galaxy NGC 1260, SN 2006gy reached extraordinary peak brightness, with absolute magnitude estimates reported near −22 and a prolonged, plateau-like light curve. That luminosity put it among the brightest supernovae ever observed.

Proposed explanations include pulsational pair-instability in a very massive star or extreme interaction between ejecta and a dense circumstellar medium; either way, SN 2006gy challenged standard core-collapse expectations and highlighted how pre-explosion mass loss can amplify radiated energy.

10. SN 1998bw — A hypernova linked to a gamma-ray burst

SN 1998bw coincided in time and position with GRB 980425, marking one of the clearest associations between a long-duration gamma-ray burst and a core-collapse supernova. Observed in 1998, the event was classified as a broad-lined Type Ic hypernova with kinetic energy estimates often cited up to ~10^52 ergs—far above typical core-collapse energies.

The temporal and spatial coincidence with GRB 980425, plus follow-up spectroscopy showing very broad lines, established that at least some GRBs arise from jet-driven explosions in massive, stripped-envelope stars.

Summary

- Historical naked-eye records (SN 185, 1006, 1054) link human observations to modern remnants and helped overturn the idea of an unchanging sky.

- Early modern events (Tycho 1572, Kepler 1604) provided precise observations that connect to modern Type Ia and remnant studies used for distance calibration.

- Nearby modern explosions like SN 1987A gave ground-truth data—neutrinos, resolved rings and long-term shock evolution—that confirmed core-collapse theory.

- Extremely luminous or GRB-linked events (SN 2006gy, SN 1998bw) expand the physics of stellar death, pointing to pair-instability processes, dense circumstellar interaction, and jet-driven hypernovae.

- Ongoing and upcoming surveys (wide transient searches and space telescopes) will almost certainly find more extreme and informative explosions in the years ahead.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.