In 1929 Edwin Hubble published evidence that galaxies are receding from us, a single observation that reshaped our view of the cosmos and set modern cosmology in motion. That moment — a simple plot of galaxy redshift against distance — made the universe dynamic instead of static and opened questions about origins, size, and fate that affect science and culture alike. These discoveries matter to non-specialists because they change how we think about beginnings, drive technologies (from detectors to data science) used across industry, and alter philosophical perspectives on our place in the universe. Cosmology is the scientific study of the universe as a whole — its history, contents, and large-scale behavior. The piece that follows presents 10 landmark discoveries that converted speculation into a precision science.

Foundational Observations that Launched Modern Cosmology

These observational pillars turned cosmology into an empirical discipline by providing measurable parameters like expansion rate and cosmic temperature. From optical spectrographs to microwave radiometers and space telescopes, instrument advances allowed quantitative tests of Big Bang ideas and eventually percent-level measurements of the universe’s ingredients. Missions such as the Hubble Space Telescope and microwave experiments on the ground and in orbit made this possible.

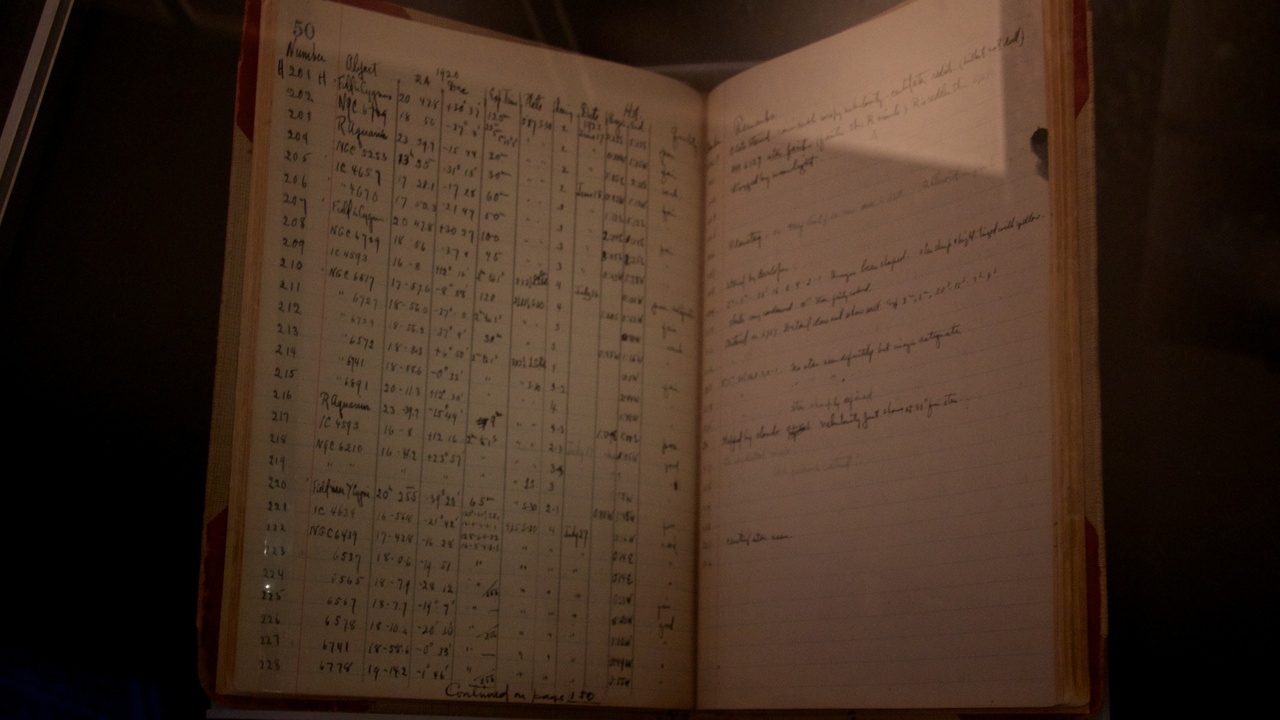

1. Hubble’s discovery of the expanding universe (1929)

Edwin Hubble’s 1929 data showed that galaxy recession velocity scales with distance, a relation now written v = H0d and known as Hubble’s law. That observation implied a dynamically evolving universe and led directly to expansion-based age estimates. Modern measurements of H0 differ slightly: the Planck team infers ≈67.4 km/s/Mpc from the CMB, while local Cepheid-plus-supernova methods give ≈73 km/s/Mpc — a tension that remains an active research topic.

The idea of expansion underlies cosmic-age estimates (roughly 13.8 billion years) and connects to technologies that use general relativity, such as GPS timing. The Hubble Space Telescope, named for Edwin Hubble, extended distance ladders far beyond Hubble’s original work and refined many distance indicators.

2. The cosmic microwave background radiation (1965)

In 1965 Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson found a persistent microwave “noise” in a horn antenna — the cosmic microwave background (CMB) — a relic glow from a hot, dense early universe. The CMB has a blackbody temperature of about 2.725 K and provides a direct snapshot of the universe roughly 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

Penzias and Wilson’s serendipitous detection (and their 1978 Nobel Prize) confirmed Big Bang predictions. Subsequent experiments and missions, including COBE, WMAP, and Planck, measured the spectrum and tiny anisotropies, pushing microwave engineering and low-noise detector technology that found uses in telecommunications and Earth remote sensing.

3. Big Bang nucleosynthesis and light-element abundances

Calculations from the 1940s–1960s predicted primordial abundances of light elements produced in the first minutes of the universe. Observations match those predictions: helium-4 has a mass fraction near 24% and the deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio is about 2–3 × 10−5, depending on the gas cloud measured.

Spectroscopic studies of metal-poor gas clouds and old stars confirm these values and constrain the baryon density and the baryon-to-photon ratio. Those constraints are crucial input for interpreting CMB data and set limits on particle-physics scenarios in the early universe.

4. Precision cosmology from CMB anisotropies (COBE → WMAP → Planck)

COBE’s detection of CMB anisotropy in 1992 showed that the early universe had tiny density variations that grew into today’s structure. WMAP (launched 2001) and Planck (2013–2018) progressively refined those measurements, turning cosmology quantitative.

Planck delivered percent-level values for key parameters — for example, matter density Ωm ≈ 0.315 and a Planck-derived H0 ≈ 67.4 km/s/Mpc — enabling tight tests of cosmological models. The data also motivated algorithmic and detector advances now used in medical imaging and large-scale data analysis.

The Dark Components: Missing Mass and Accelerated Expansion

Two unexpected components—dark matter and dark energy—together dominate the universe’s energy budget and reshaped cosmology. Their discovery came from anomalies in rotation curves, galaxy clusters, and distant supernovae, and they forced physicists to consider new particles, fields, or modifications to gravity. Research programs worldwide now aim to identify the nature of these components because they control structure formation and the universe’s ultimate fate.

5. Evidence for dark matter (Zwicky, Rubin, and rotation curves)

As early as 1933 Fritz Zwicky noted missing mass in galaxy clusters, but the evidence became compelling in the 1970s when Vera Rubin measured flat galaxy rotation curves implying unseen mass in galactic halos. Today roughly 85% of the universe’s matter appears to be non-baryonic dark matter.

Gravitational lensing studies, notably the Bullet Cluster (2006), show mass distributions offset from the luminous gas, strengthening the case for dark matter as a distinct component. Searches now span astronomical surveys, direct-detection experiments (for example, XENON1T), and collider efforts. The push for sensitive CCDs and data pipelines in these programs has benefited broader imaging and analysis technologies.

6. Discovery of the accelerating universe and dark energy (1998)

Measurements of distant Type Ia supernovae in 1998 by the Supernova Cosmology Project (Perlmutter) and the High-z Supernova Search Team (Riess, Schmidt and collaborators) found those explosions dimmer than expected, implying the expansion of the universe is accelerating. This led to the idea of dark energy, which contributes about 68% of the cosmic energy density.

The result changed expectations for cosmic destiny and raised theoretical puzzles about vacuum energy versus dynamic fields. The surveys developed calibration, detector, and analysis techniques that strengthened optical astronomy overall and set the stage for wide-field programs mapping expansion history.

Structures, Compact Objects, and New Cosmic Messengers

These greatest discoveries in cosmology include how matter organizes into a cosmic web, the role of black holes and quasars in galaxy evolution, and the arrival of gravitational waves as a new observational channel. Together they opened fresh windows on the universe and drove advances in detectors, computing, and cross-disciplinary methods.

7. Mapping large-scale structure and the cosmic web (redshift surveys)

Redshift surveys exposed a web of filaments, clusters, and voids rather than a random galaxy distribution. Early work by the CfA survey in the 1980s gave the first slices; 2dF and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) in the 2000s expanded maps to millions of galaxies and produced striking three-dimensional views of structure.

Those catalogs enabled detection of the baryon acoustic oscillation (BAO) scale, a standard ruler used to measure expansion history. The statistical techniques and big-data tools developed for surveys now inform data science across many fields.

8. Discovery and cosmological role of quasars and supermassive black holes

Quasars, first identified in the early 1960s with the notable 3C 273 (identified in 1963), revealed enormously luminous nuclei powered by accretion onto supermassive black holes. Measurements show black-hole masses ranging from millions to several billion solar masses in massive galaxies.

Active galactic nucleus (AGN) feedback — energetic outflows and radiation from accreting black holes — affects star formation and galaxy evolution. Observatories like Chandra and the Event Horizon Telescope have advanced imaging and detector approaches with spin-offs in radio and X-ray technologies.

9. Direct detection of gravitational waves (2015)

On Sept 14, 2015 LIGO recorded GW150914, the first direct detection of gravitational waves from a binary black-hole merger (component masses ≈36 and 29 M☉). The observation confirmed a prediction of general relativity and launched gravitational-wave astronomy; the Nobel Prize in Physics followed in 2017 for key LIGO contributors.

Gravitational-wave detections — including the neutron-star merger GW170817 with electromagnetic counterparts — enabled multi-messenger studies of dense-matter physics and cosmology. The precision interferometry and vibration-isolation techniques developed for LIGO have had impacts on control engineering and metrology.

10. Galaxy surveys and the refinement of cosmic history (growth of structure)

Deep imaging and multiwavelength campaigns traced galaxy formation across time. The Hubble Deep Field (1995) provided the first deep look back billions of years; follow-up programs like GOODS and CANDELS extended that reach and helped map star-formation rate density versus redshift up to lookback times exceeding 10 billion years.

These surveys refined models for mass assembly, star formation, and feedback. Upcoming facilities such as the Vera Rubin Observatory (LSST) promise surveys of unprecedented depth and cadence, while improvements in detectors and image-processing algorithms continue to benefit imaging sciences broadly.

Summary

- Modern cosmology became an empirical, precision discipline when observations—from Hubble’s 1929 redshifts to Planck’s percent-level CMB results—provided measurable parameters for the universe.

- Two surprising components dominate the cosmos: dark matter (evidence from Rubin’s rotation curves and lensing, e.g., the Bullet Cluster) and dark energy (discovered via Type Ia supernovae in 1998), together comprising roughly 95% of the universe’s energy–matter budget.

- New windows — large-scale redshift surveys (SDSS, BAO), deep imaging (Hubble Deep Field, GOODS), and gravitational waves (GW150914 on Sept 14, 2015) — have connected small-scale physics to cosmic history and opened multi-messenger cosmology.

- Key programs such as Planck, LIGO, and SDSS illustrate how coordinated missions and better instruments turned qualitative ideas into quantitative tests and spawned technologies used beyond astronomy.

- Which questions will the next decade answer about the universe — the true nature of dark components, the H0 tension, or new messengers — remains an open and exciting challenge.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.