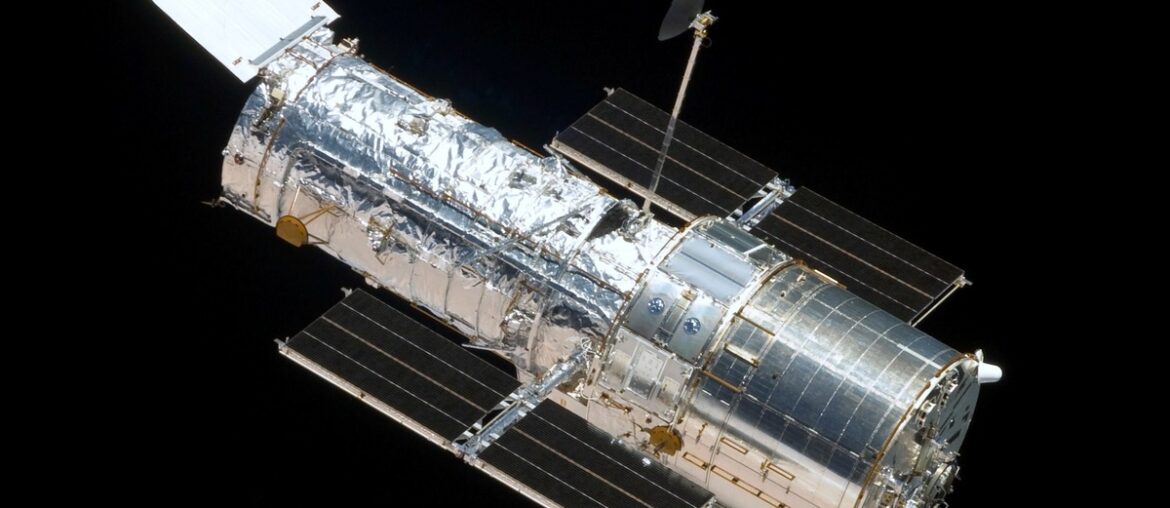

When Hubble launched in 1990 it transformed astronomy with a 2.4‑metre mirror; when the James Webb Space Telescope arrived in 2021 it pushed infrared sensitivity and resolution even further. That three-decade leap shows how quickly space astronomy advances and why the decade ahead is so exciting.

Over the next ten to twenty years a mix of funded missions and ambitious concept observatories will hunt for habitable worlds, map cosmic structure, and reveal high-energy processes that shape galaxies. These instruments will also drive technology that finds uses back on Earth.

This concise rundown covers 10 future space telescopes—near-term launches and high-priority concepts for the 2030s—worth watching for exoplanet discoveries, cosmology, and high-energy astrophysics.

Flagship optical and infrared observatories

Optical and infrared space telescopes deliver unrivaled sensitivity and stable observing conditions that ground telescopes can’t match because of atmospheric blurring and absorption. Large apertures increase light‑gathering and angular resolution, while advanced instruments—imagers and spectrographs—turn faint photons into detailed physical measurements.

For exoplanets, high contrast techniques such as coronagraphs and external starshades suppress starlight so spectra of nearby planets become attainable. For cosmology and galaxy evolution, deep, stable imaging and spectroscopy let us measure faint galaxies and precise redshifts.

The next four entries range from funded near-term flagships to 2030s-era concept studies for 8–15 metre‑class observatories that would vastly extend Hubble’s reach. Below are the missions to watch.

1. Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (Roman)

Roman is a NASA flagship scheduled for the mid‑2020s and built around a 2.4‑metre primary mirror paired with a Wide Field Instrument (WFI) that offers roughly a 0.28 square‑degree field of view—about 100 times Hubble’s imaging area per exposure.

That large survey capability lets Roman carry out wide cosmology programs to refine dark energy measurements and run a microlensing survey expected to find thousands of exoplanets, especially cold and distant worlds that other methods miss.

Roman also includes the Coronagraph Instrument (CGI) as a technology demonstration, testing high‑contrast imaging techniques that will build target lists and technical know‑how for direct‑imaging follow-ups by later flagships.

2. Habitable Worlds Observatory (NASA concept)

The Habitable Worlds Observatory is NASA’s community-backed vision, recommended in the most recent decadal survey, for a 2030s flagship focused on directly detecting and characterizing Earth‑like planets.

At a high level the concept emphasizes a large aperture with broad ultraviolet‑to‑infrared spectroscopy capable of searching for biosignatures such as oxygen, water vapor, and methane in temperate atmospheres.

Finding compelling candidate biosignatures would transform the search for life by moving from statistical hints to specific targets for follow-up and would drive astrobiology for decades.

3. LUVOIR (Large UV/Optical/IR Surveyor) — concept

LUVOIR was studied as a multi‑purpose flagship with two reference architectures—roughly an 8‑metre (LUVOIR‑B) and a 15‑metre (LUVOIR‑A) primary mirror—designed to cover UV through infrared wavelengths.

With that aperture range LUVOIR would enable ultra‑deep imaging of galaxies, high‑resolution UV spectroscopy for stellar and interstellar medium studies, and high‑contrast exoplanet imaging to probe atmospheres of faint planets.

UV capability is especially valuable for measuring stellar winds, radiation environments, and the chemical processes that affect planetary atmospheres, while a 15‑metre mirror would vastly improve faint‑object spectroscopy compared to Hubble.

4. HabEx (Habitable Exoplanet Observatory) — concept

HabEx is a mission concept optimized for directly imaging habitable‑zone planets, with studied designs including a roughly 4‑metre telescope and the option to use an external occulter, or starshade, to block starlight.

Starshades operate by flying tens of thousands of kilometres from the telescope to cast a deep shadow, allowing spectroscopy of faint planets very close to bright host stars without relying solely on a coronagraph.

By prioritizing habitable‑zone Earth analogs, HabEx would identify and characterize the most promising targets for biosignature searches and advance starlight‑suppression techniques critical for future missions.

High-energy and far-infrared observatories

X‑rays and far‑infrared light probe extremes that optical telescopes cannot: hot plasmas around black holes, shock‑heated gas in galaxy clusters, and cold dust and water in planet‑forming disks. Earth’s atmosphere blocks much of these bands, so space platforms are essential.

The three telescopes below—an ESA X‑ray flagship planned for the 2030s and two U.S. concept studies—each access unique physical regimes, from energetic black‑hole growth to the chemistry of water and organics in cold regions.

Together they will connect small‑scale planet formation chemistry to large‑scale energetic feedback that shapes galaxy evolution.

5. Athena (Advanced Telescope for High ENergy Astrophysics) — ESA

Athena is ESA’s next large X‑ray observatory targeted for the early‑to‑mid 2030s, designed to survey hot baryons in galaxy clusters and trace supermassive black hole growth across cosmic time.

Its high‑resolution spectrometer, the X‑IFU, will provide precise velocity and temperature diagnostics of hot gas, letting astronomers perform a baryon census and measure the mechanics of feedback that regulate galaxy evolution.

Athena’s sensitivity represents a major step up from earlier X‑ray missions, opening studies of fainter and more distant X‑ray sources that inform models of cosmic structure and background radiation.

6. Lynx X‑ray Observatory (NASA concept)

Lynx is a NASA concept that aims to pair Chandra‑like sub‑arcsecond angular resolution with a much larger collecting area and greatly improved sensitivity.

That combination would let Lynx detect the earliest black‑hole seeds, map faint hot gas in and around galaxies, and push deep X‑ray imaging to new depths, revealing populations and structures currently out of reach.

Developing Lynx‑class optics and detectors also promises spillover benefits for precision X‑ray instrumentation used in medical imaging and materials science.

7. Origins Space Telescope (OST) — far‑IR concept

Origins is a concept for a far‑infrared observatory that would surpass missions like Herschel in sensitivity, targeting cold gas, dust, water, and complex organics in protoplanetary disks and distant, dust‑obscured galaxies.

By detecting faint water lines and organic molecular signatures in planet‑forming regions, Origins would trace how volatiles assemble and whether water delivery to planets is common across star systems.

As a concept study, Origins would need future selection and funding, but its science case links directly to questions about the chemical precursors of life and the hidden side of cosmic star formation.

Survey and exoplanet-focused missions

Not every transformative mission is a giant flagship; specialized surveyors and exoplanet‑focused observatories deliver the statistical catalogs and demographic studies that underpin follow‑up science.

Wide‑field and all‑sky surveys produce target lists and population context, while dedicated exoplanet missions provide atmospheric demographics that inform which worlds deserve detailed characterization by larger telescopes.

Below are three missions—launching in the mid to late 2020s—that will feed the next generation of flagship observatories and provide immediate new datasets.

8. ARIEL (Atmospheric Remote‑sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large‑survey) — ESA

ARIEL is designed to survey the atmospheres of a large sample of transiting exoplanets, with a planned launch in the late 2020s and an objective to observe on the order of ~1,000 planetary atmospheres.

By building a comparative catalog across hot Jupiters, warm Neptunes, and sub‑Neptunes, ARIEL will reveal trends in composition, cloud properties, and formation history that single‑object studies can’t provide.

Those statistical results will help prioritize targets for flagship direct‑imaging missions and improve theoretical models of planetary formation and migration.

9. PLATO (PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars) — ESA

PLATO, expected to launch in the mid‑2020s, focuses on finding and characterizing terrestrial planets around bright, nearby stars using long‑duration, wide‑field photometry combined with asteroseismology to measure stellar ages precisely.

Knowing a host star’s radius and age tightens estimates of planet radius and evolutionary state, which is crucial for assessing habitability and selecting targets for atmospheric follow‑up.

PLATO’s emphasis on bright solar‑type stars increases the chances of discovering small planets in habitable zones that are accessible to both ground‑based and space‑based follow‑up.

10. SPHEREx (Spectro‑Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and Ices Explorer) — NASA

SPHEREx will perform an all‑sky near‑infrared spectrophotometric survey, mapping the sky between roughly 0.75 and 5 microns with a planned mid‑2020s launch.

Its science goals span cosmology—constraining inflationary models—to galaxy evolution and an inventory of ices and organics in molecular clouds and protoplanetary systems.

SPHEREx will deliver a public spectral atlas that supports countless follow‑up programs by JWST, Roman, ground telescopes, and the next generation of observatories.

Summary

- These ten telescopes mix near‑term funded missions (Roman, ARIEL, PLATO, SPHEREx) with visionary 2030s concepts (LUVOIR, HabEx, Habitable Worlds Observatory) that could reshape exoplanet and galaxy studies.

- Survey missions supply catalogs and statistical context, while flagship optical/IR and high‑energy observatories provide the high‑resolution spectroscopy and direct imaging needed for detailed characterization.

- Advances in instrumentation—coronagraphs, starshades, high‑resolution X‑ray spectrometers, and far‑IR detectors—are central to the next wave of discoveries and have practical spin‑offs beyond astronomy.

- Near‑term launches will already expand our planetary census and spectral atlases, while decadal‑recommended flagships aim to identify and study potentially habitable worlds in the 2030s.

- Keep an eye on mission milestones and data releases—these observatories will steadily fill in the map between small‑scale planet chemistry and the large‑scale forces that shape the cosmos.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.