Comets have traced bright arcs across the sky for millennia, inspiring stories and driving scientific curiosity as telescopes and spacecraft revealed their icy makeup. Today they remain key to understanding the Solar System’s past and the processes shaping small bodies.

There are 25 Famous Comets, ranging from 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko to Wirtanen. Entries list Designation, Orbital period (yr), Notable for — you’ll find below.

How are comets like 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko and Wirtanen named?

Comet names combine formal designations (provisional codes or periodic numbers) with the discoverer(s) or survey that found them; short-period comets often get a number like 67P, while long-period comets keep year-based codes. The table below shows each comet’s official designation and orbital period for clarity.

When can I see these comets from Earth?

Visibility depends on a comet’s orbit and brightness: some short-period comets return predictably but are faint, while some long-period comets become bright but unpredictable. For viewing, check current ephemerides or astronomy apps and use the orbital period info you’ll find below to estimate return windows.

Famous Comets

| Name | Designation | Orbital period (yr) | Notable for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Halley | 1P/Halley | 76 | Iconic periodic comet seen for millennia |

| Hale-Bopp | C/1995 O1 | 2,533 | Exceptionally bright long-period comet of 1997 |

| Hyakutake | C/1996 B2 | non-periodic | Very close 1996 pass with dramatic plasma tail |

| Encke | 2P/Encke | 3.30 | Shortest orbital period among named comets |

| Swift-Tuttle | 109P/Swift-Tuttle | 133 | Source of the Perseid meteor shower |

| Tempel 1 | 9P/Tempel 1 | 5.50 | Target of NASA’s Deep Impact mission |

| 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko | 67P | 6.45 | Rosetta mission target with Philae lander |

| Shoemaker-Levy 9 | D/1993 F2 | non-periodic | Fragmented and impacted Jupiter in 1994 |

| ISON | C/2012 S1 | non-periodic | High-profile 2013 sungrazing comet that disintegrated |

| NEOWISE | C/2020 F3 | non-periodic | Bright, widely seen naked-eye comet in 2020 |

| McNaught | C/2006 P1 | non-periodic | Extremely bright daytime-visible comet in 2007 |

| Lovejoy (2011) | C/2011 W3 | non-periodic | Sungrazing comet that survived perihelion |

| Lovejoy (2014) | C/2014 Q2 | non-periodic | Bright, easy-to-see comet in late 2014 |

| Kohoutek | C/1973 E1 | non-periodic | Hyped 1973 comet that underperformed visually |

| West | C/1975 V1 | non-periodic | Dramatic 1976 Southern Hemisphere great comet |

| Holmes | 17P/Holmes | 6.88 | Huge 2007 outburst made it briefly naked-eye |

| Wild 2 | 81P/Wild | 6.40 | Stardust sample-return mission target |

| Borrelly | 19P/Borrelly | 6.86 | Deep Space 1 flyby revealed dark, active nucleus |

| Hartley 2 | 103P/Hartley 2 | 6.46 | Visited by EPOXI spacecraft showing active jets |

| Tempel-Tuttle | 55P/Tempel–Tuttle | 33 | Parent of the Leonid meteor shower |

| Giacobini–Zinner | 21P/Giacobini–Zinner | 6.62 | First comet visited by a spacecraft (ICE) in 1985 |

| Biela | 3D/Biela | 6.60 | Famous 19th-century breakup linked to meteor showers |

| Siding Spring | C/2013 A1 | non-periodic | Close 2014 flyby of Mars observed by spacecraft |

| Wirtanen | 46P/Wirtanen | 5.44 | Close, bright passer in 2018 and former Rosetta target |

| Borisov | 2I/Borisov | non-periodic | First confirmed interstellar comet discovered in 2019 |

Images and Descriptions

Halley

Halley’s Comet is the best-known periodic comet visible every 76 years, recorded across human history. Its 1910 and 1986 returns shaped modern astronomy and public imagination; predictions about its orbit helped develop celestial mechanics.

Hale-Bopp

Hale-Bopp dazzled viewers worldwide in 1997 with an unusually bright, long-lasting display and dual tails. Its visibility to the unaided eye for months revived popular interest and led to extensive scientific study of long-period comet composition.

Hyakutake

Hyakutake passed unusually close to Earth in 1996, producing an impressive plasma tail and intense scientific observations. Its proximity offered detailed studies of cometary gas and dust and inspired public awe despite its brief, long-period visit.

Encke

Encke is known for the shortest confirmed orbital period of any named comet, about 3.3 years, and for influencing studies of cometary dynamics and meteor showers. Its frequent returns make it a staple of professional and amateur tracking programs.

Swift-Tuttle

Swift–Tuttle, source of the Perseid meteor shower, has a long, 133-year orbit and is one of the largest known periodic comets. Its size and future close approaches draw attention for impact risk assessment and meteor forecasting.

Tempel 1

Tempel 1 was the target of NASA’s Deep Impact mission, which struck the nucleus in 2005 to study interior composition. Observations revealed layered structure and volatile behavior, deepening understanding of short-period comet evolution.

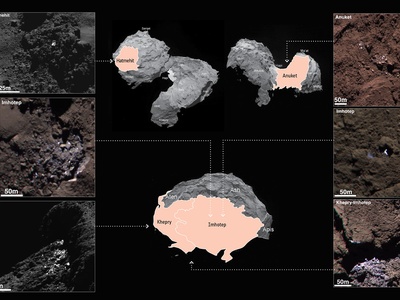

67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko

67P was explored up close by ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft, which orbited and landed the Philae probe in 2014. The mission transformed comet science by mapping surface features, chemistry, and seasonal behavior over multiple years.

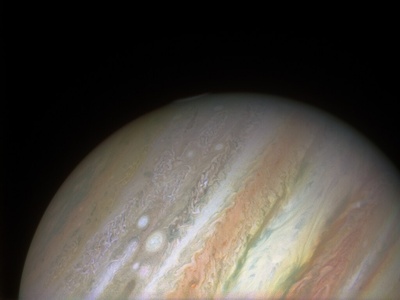

Shoemaker-Levy 9

Shoemaker–Levy 9 famously fragmented and collided with Jupiter in 1994, giving humanity its first observed major impact on another planet. The event provided unique data on impact physics and Jupiter’s atmosphere.

ISON

Comet ISON generated intense media attention in 2013 as hopes grew for a spectacular naked-eye display, but it disintegrated during perihelion. The drama highlighted challenges in predicting brightness and cometary fragility near the Sun.

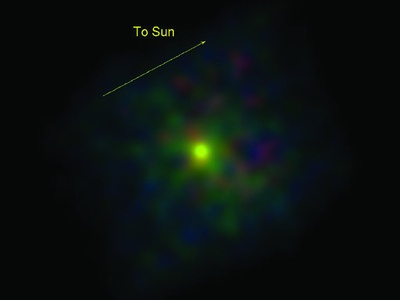

NEOWISE

Comet NEOWISE brightened into an easy naked-eye object in 2020, offering broad public visibility during a global pandemic. Observers worldwide enjoyed a lengthy tail display and amateur photography surged, renewing interest in bright comets.

McNaught

Comet McNaught became spectacularly bright in 2007, displaying a massive, icy dust tail visible in daylight near perihelion in the Southern Hemisphere. It stands as one of the brightest comets of the 21st century.

Lovejoy (2011)

Lovejoy (C/2011 W3) amazed observers by surviving a close plunge past the Sun in 2011, emerging with a luminous tail. Its survival challenged expectations for sungrazing comets and captivated both scientists and the public.

Lovejoy (2014)

Lovejoy (C/2014 Q2) became a bright, easy-to-see comet in late 2014, sporting a dust-rich tail and greenish coma. It delighted backyard observers and provided spectra revealing typical cometary gas emissions.

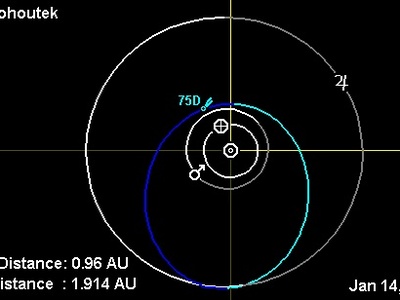

Kohoutek

Kohoutek arrived in 1973 amid huge expectations for a ‘comet of the century’ but underperformed visually, teaching lessons about unpredictable brightness forecasts. It remains historically famous for media hype and scientific scrutiny.

West

Comet West (C/1975 V1) stunned observers in 1976 with multiple bright tails and an intensely bright head for Southern Hemisphere viewers. Its dramatic fragmentation and tail display rank it among modern great comets.

Holmes

17P/Holmes dramatically brightened by a factor of a million in 2007, becoming visible to the naked eye as a diffuse ‘outburst’ and offering scientists a rare chance to study sudden cometary activity and expanding dust clouds.

Wild 2

81P/Wild 2 was visited by NASA’s Stardust mission, which returned dust samples to Earth in 2006. Analysis of the grains revealed primitive materials and surprised scientists with signs of high-temperature minerals.

Borrelly

19P/Borrelly was mapped by NASA’s Deep Space 1 spacecraft in 2001, revealing a dark, rugged nucleus with active jets. The mission provided detailed imaging and helped refine methods for close comet encounters.

Hartley 2

103P/Hartley 2 was visited by NASA’s EPOXI spacecraft in 2010, revealing a small, peanut-shaped nucleus and strong outgassing jets. Observations linked its behavior to active regions and seasonal surface changes.

Tempel-Tuttle

55P/Tempel–Tuttle is the parent comet of the Leonid meteor shower and produces spectacular meteor storms when Earth intersects dense debris. Its roughly 33-year orbit led to historically dramatic meteor displays and scientific study.

Giacobini–Zinner

21P/Giacobini–Zinner was visited by the International Cometary Explorer in 1985, becoming the first comet flown through by a spacecraft. It’s also the parent of the Giacobinid meteor stream and notable for periodic photometric changes.

Biela

Biela’s Comet split into pieces in the 19th century and later disappeared, historically linked to the Andromedid meteor showers. Its breakup provided early evidence that comets can fragment and influence meteor activity.

Siding Spring

Comet C/2013 A1 Siding Spring made a remarkably close pass to Mars in 2014, sweeping through the Martian environment and prompting spacecraft observations to study dust impacts and induced atmosphere changes.

Wirtanen

46P/Wirtanen was a highly anticipated close passer in 2018, brightening for observers and offering a good view of a small, active nucleus. It was briefly the target for Rosetta before mission retargeting.

Borisov

2I/Borisov is the second known interstellar object and the first confirmed interstellar comet, discovered in 2019. Its hyperbolic trajectory and native chemistry offered a rare opportunity to compare cometary materials from another star system.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.