In 1929 Edwin Hubble published evidence that galaxies are receding from us, a discovery that led to the idea that the universe is expanding. The Hubble constant measures the rate at which cosmic distances increase — usually expressed in kilometers per second per megaparsec (km/s/Mpc) — and pinning down its value matters because it fixes the universe’s characteristic timescale, helps determine cosmic contents like dark energy and matter, and can point to new physics if measurements disagree. This piece lays out seven clear facts about the hubble constant that explain what H0 is, how it’s measured, why different methods currently give different answers, and what’s coming next to resolve the puzzle.

Foundations: What the Hubble Constant Actually Measures

To understand why H0 matters, start with what it quantifies and how astronomers first inferred it. The following three points define the quantity, recall Hubble’s original evidence, and summarize modern approaches to measuring the expansion rate.

1. What the Hubble Constant Measures — H0, its units, and meaning

H0 is the present-day expansion rate of the universe and is conventionally given in km/s/Mpc (kilometers per second per megaparsec). One megaparsec (1 Mpc) is about 3.09×1022 meters, so H0 expresses how much recessional velocity increases with physical distance.

As a concrete example, H0 = 70 km/s/Mpc implies a galaxy 10 Mpc away recedes at roughly 700 km/s (10 × 70). Think of it like a speed rule that scales with separation: double the distance, double the recession speed.

2. The discovery that started it: Hubble’s 1929 observation

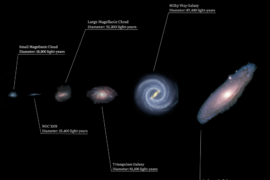

In 1929 Edwin Hubble published a relation between galaxy redshift and distance, using Cepheid variable stars in nearby galaxies as distance markers. That velocity–distance plot — the original Hubble diagram — provided the first quantitative evidence for cosmic expansion.

Hubble measured recession speeds of order hundreds to a few thousand km/s for the galaxies he could observe, translating Doppler-like redshifts into velocities at low redshift. His work relied on Cepheids as the distance step that made the velocity trend meaningful.

3. How astronomers measure H0 today: distance ladders and the CMB

Modern measurements follow two complementary strategies. Local, “distance ladder” methods calibrate geometric distances (parallaxes from Gaia) to Cepheids or the Tip of the Red Giant Branch, use those to calibrate Type Ia supernovae, and infer H0 from nearby expansion (SH0ES, led by Adam Riess). Typical local results cluster near ~73 km/s/Mpc.

The other approach infers H0 from the early universe: cosmic microwave background (CMB) maps (ESA/NASA’s Planck mission) constrain the physical densities and expansion history within the ΛCDM model, yielding a best-fit H0 around ~67 km/s/Mpc (Planck 2018 results). That value is model-dependent because it assumes the standard cosmological framework.

Improved parallaxes from Gaia and high-resolution imaging from the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) have tightened local calibrations, while Planck’s precision CMB maps have tightened the early-universe inference — which is why the two approaches now disagree at a level that matters.

Why the Hubble Constant Matters for Cosmology

Knowing H0 precisely does more than pin down a number. It fixes a timescale for the universe and works with other parameters to reveal the composition, geometry, and ultimate fate of cosmic expansion.

4. H0 sets a cosmic timescale: implications for the universe’s age

At zeroth order, the inverse of H0 gives a characteristic age: t ~ 1/H0. Using H0 = 70 km/s/Mpc converts to an age near 14 billion years (roughly 1.4×1010 years) for the simple estimate.

Small shifts matter: H0 = 67 km/s/Mpc pushes the simple inverse-age estimate older by a few hundred million years, while H0 = 73 km/s/Mpc makes it younger by a comparable amount. Those shifts are significant when comparing to independent age indicators like the oldest globular clusters (≈13.4 billion years).

5. H0 and the universe’s contents: how it constrains matter and dark energy

H0 is not fitted in isolation; cosmological analyses determine H0 alongside parameters such as Ωm (matter density) and ΩΛ (dark energy fraction) within the ΛCDM framework. A higher H0 typically pushes fits toward different combinations of matter and dark energy to preserve the observed CMB acoustic scale.

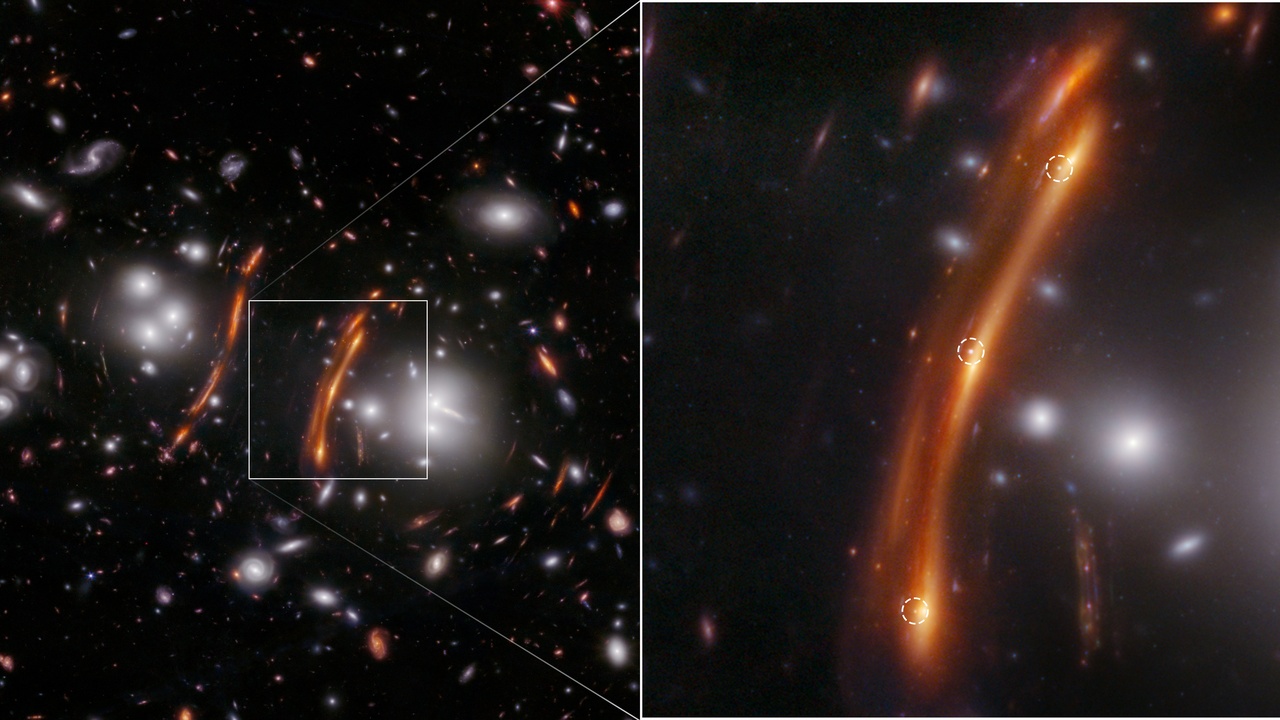

For example, Planck CMB data combined with baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO) tightly constrain Ωm and H0 jointly. If H0 is higher than the CMB-inferred value, either unknown systematics exist or extensions to ΛCDM (early dark energy, extra relativistic species, or altered neutrino physics) are needed — and those extensions leave signatures in BAO, lensing, or structure growth that surveys like DESI can test.

Thus, pinning down H0 refines our estimates of cosmic contents and tests whether the standard model suffices to explain the universe’s expansion history.

Current Debates, Practical Implications, and What’s Next

The contemporary story centers on the so-called Hubble tension: two extremely precise but inconsistent routes to H0 give different answers, and that disagreement could either signal subtle measurement issues or new physics beyond ΛCDM.

6. The Hubble tension — two precise answers that don’t agree

The tension is a statistically significant difference between local measurements and early-universe inferences. Representative numbers are Planck (2018 CMB) ≈ 67.4 km/s/Mpc versus SH0ES (Riess et al., 2021) ≈ 73.2 km/s/Mpc — a roughly 8–9% discrepancy, or several standard deviations depending on dataset combinations.

Because both sides claim percent-level precision, attention has turned to independent cross-checks: H0 values from water megamasers, time delays in gravitational lensing (H0LiCOW and follow-ups), and the Tip of the Red Giant Branch method provide alternative routes that help reveal whether calibration or modeling errors drive the mismatch.

7. Why the disagreement matters and how we might resolve it

The stakes are high because resolving the tension either tightens confidence in ΛCDM or points to new physics such as a brief early-dark-energy component, extra relativistic particle species, or modified gravity. Each proposed fix would also alter other observables, so multi-probe consistency tests matter.

Near-term progress looks promising. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is refining distances to supernova hosts, Gaia Data Releases improve parallax calibrations, and surveys like DESI plus the future Roman Space Telescope will map BAO and large-scale structure with much greater precision. Over the next 3–5 years these programs should reduce systematic uncertainty and either reconcile the values or make a strong case for physics beyond the standard model.

Resolving H0 affects derived limits on neutrino mass, dark energy properties, and the inferred timeline for structure formation — so the cosmology community is watching the outcome closely.

Summary

- H0 describes the present expansion rate in km/s/Mpc and gives a characteristic cosmic timescale (age ≈ 1/H0).

- Edwin Hubble’s 1929 velocity–distance relation (via Cepheids) began the measurement tradition that today uses Cepheids, TRGB, Type Ia supernovae, and the CMB (Planck) as complementary routes.

- Different high-precision methods currently disagree by about 8–9% (Planck ≈ 67 km/s/Mpc vs local ladders ≈ 73 km/s/Mpc), the persistent Hubble tension.

- The tension could reflect unknown systematics or new physics (early dark energy, extra relativistic species, modified gravity), and each possibility has testable signatures in other datasets.

- Upcoming and ongoing programs — JWST, Gaia DR3/DR4, DESI, and Roman — should clarify calibration issues and either resolve the tension or reveal new cosmology in the next few years.

Watch for results from those missions over the coming 3–5 years; their findings will reshape how confidently we state the universe’s age and composition.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.