In 964 AD the Persian astronomer Abd al‑Rahman al‑Sufi sketched what he called a “small cloud”—the first recorded description of the object we now know as the Andromeda Galaxy.

Understanding that “small cloud” matters because Andromeda is a principal member of the Local Group, a testing ground for how spiral galaxies form and evolve, and a neighbor whose future orbit will reshape our galaxy over billions of years. This article presents 10 clear, digestible facts about the Andromeda Galaxy that explain its size, motion, structure, history of observation, and why it matters to astronomers and the public alike. Below are 10 facts about the Andromeda Galaxy that make the object both familiar and profoundly informative.

Basics: Where Andromeda fits in the cosmos

M31 is the Messier object number 31 and one of the largest members of the Local Group. Historical records stretch from al‑Sufi’s 964 AD note to Charles Messier’s 1764 catalog entry, and Edwin Hubble’s 1920s Cepheid work established its status as an external galaxy. These basic identifiers—catalog name, group membership, and discovery history—establish identity and context for the facts that follow.

1. M31 — Andromeda’s catalog name and neighbor-status

M31 is the same object commonly called the Andromeda Galaxy and appears in catalogs as Messier 31. It’s one of the largest and brightest members of the Local Group, which includes roughly 50–60 galaxies ranging from dwarfs to major spirals. Observers have recorded Andromeda for more than a millennium: Abd al‑Rahman al‑Sufi drew it in 964 AD and Charles Messier listed it in his 1764 catalog to help comet hunters avoid confusion.

Edwin Hubble’s detection of Cepheid variable stars in Andromeda in 1923–1924 provided the decisive evidence that the object lies far outside the Milky Way, establishing the existence of other galaxies. Catalog names like M31 matter because they let astronomers cross‑reference observations across wavelengths and centuries, anchoring studies of structure, motion, and evolution.

2. Distance: roughly 2.5 million light‑years away

Andromeda sits at about 2.5 million light‑years from us—modern estimates commonly quote ≈2.537×10^6 light‑years. That distance was first measured with Cepheid variables by Edwin Hubble in the early 1920s and has been refined using Hubble Space Telescope observations and other standard candles as part of the cosmic distance ladder.

To put the scale in everyday terms: Andromeda is roughly 25 million times farther away than Pluto is from the Sun. Knowing that distance matters because it calibrates the scale of the nearby universe, anchors measurements of galaxy luminosity and mass, and tells us the object is clearly external to the Milky Way rather than a nebula inside it.

3. Visible to the naked eye under dark skies (apparent magnitude ≈3.4)

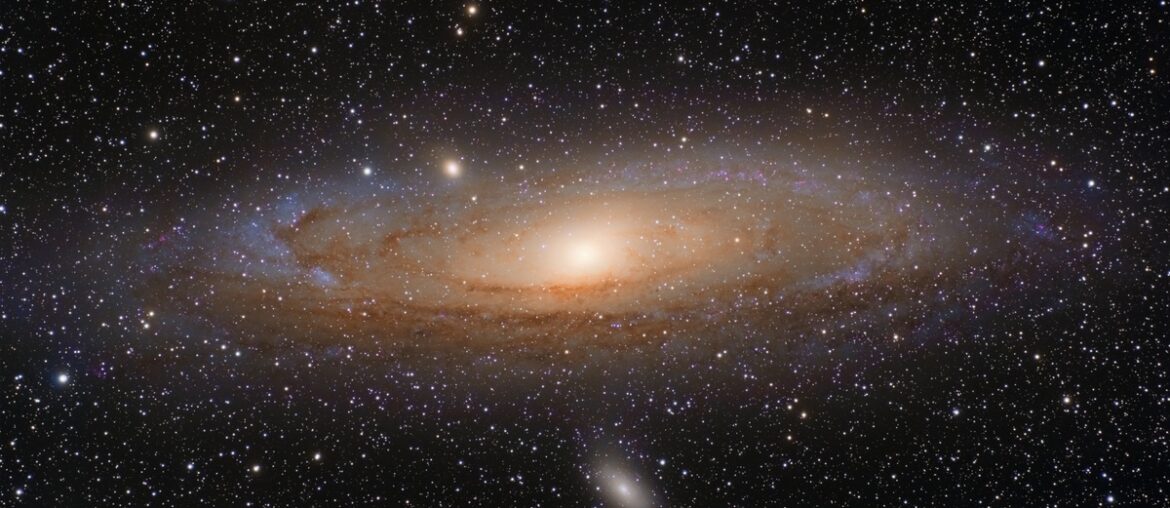

Despite being millions of light‑years away, Andromeda is bright enough to be seen without optical aid from dark, rural skies; its integrated apparent magnitude is about 3.4. In the Northern Hemisphere it climbs high in autumn evenings, and under good conditions it appears as a faint, elongated smudge rather than a pinpoint star.

That visibility makes Andromeda a gateway object for amateur astronomers and the public: it features at star parties and backyard observing sessions, where simple binoculars already reveal structure and telescopes display star clouds, dust lanes, and companion galaxies that connect everyday stargazing to professional extragalactic research.

Size, mass and internal structure

Size and structure shape a galaxy’s dynamics, star formation, and merger history. Andromeda rivals or exceeds the Milky Way in several measures: a very large diameter and stellar halo, prominent spiral arms and ring features, and a dense central bulge with a massive black hole. These properties determine how it will behave as it interacts with companions and with our galaxy.

4. Diameter: about 220,000 light‑years across

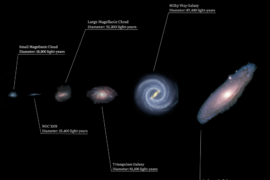

Andromeda’s diameter is commonly given as roughly 220,000 light‑years, significantly larger than the classic Milky Way disk estimate of about 100,000–150,000 light‑years. That larger scale emerges when surveys map extended stellar halos and neutral hydrogen (HI) that reach well beyond the bright disk.

Size estimates come from star counts, deep optical imaging, and radio observations that trace gas. Different methods and depth limits produce slightly different answers, but the implication is consistent: Andromeda exerts a wide gravitational influence and hosts an extensive stellar halo shaped by past accretion events.

5. Star population: roughly one trillion stars

Current estimates place Andromeda’s stellar population near 1×10^12 stars—about a trillion—making it larger in star count than many estimates of the Milky Way (often quoted at 200–400 billion). Astronomers infer star counts from integrated light, mass‑to‑light ratios, and resolved star surveys in the disk and halo.

Knowing how many stars a galaxy contains helps predict chemical enrichment, supernova rates, and the number of potential planetary systems. Deep surveys such as Pan‑STARRS and SDSS, combined with infrared and radio data, refine mass estimates and reveal how the stellar population spreads across disk, bulge, and halo.

6. A massive central bulge and a large black hole

Andromeda displays a prominent, dense central bulge that dominates its inner light profile, and it hosts a supermassive black hole with a mass on the order of 1–2×10^8 solar masses (about 100–200 million M☉). Astronomers derive that figure from stellar velocity dispersions and gas dynamics measured near the core.

That black hole is far more massive than the Milky Way’s central black hole (≈4×10^6 M☉), and its gravity helps set orbital speeds for stars near the nucleus while contributing modestly to the galaxy’s overall dynamics. Measurements come from spectroscopy of central stars and high‑resolution imaging that trace motions over time.

Motion and the future between galaxies

Galaxies move through space under the pull of gravity, and Andromeda’s motion relative to the Milky Way determines whether the two will remain neighbors or merge. Astronomers combine Doppler spectroscopy with proper‑motion measurements from Hubble and Gaia to compute current velocities and run N‑body simulations that forecast future interactions.

7. Andromeda is moving toward us at about 110 km/s

Spectroscopic measurements show Andromeda has a radial velocity toward the Milky Way of roughly 110 kilometers per second, revealed as a blue shift in its spectral lines. That radial component is the dominant measured approach; tangential (sideways) motion is small but constrained by recent proper‑motion studies.

Combining the radial speed with limits on tangential velocity gives astronomers a clear sense of the gravitational dance between the two galaxies and is a key input for simulations that project when and how the interaction will unfold.

8. Predicted collision: merger in roughly 4–5 billion years

Current best estimates place the first close passage or collision between Andromeda and the Milky Way at about 4–5 billion years from now, with a fully merged remnant—often called “Milkomeda”—forming several billion years after that. Those timelines come from N‑body simulations that combine measured velocities, mass estimates, and models of dark matter halos.

Will individual stars collide? Extremely unlikely; the distances between stars are enormous compared with stellar sizes. The more likely effects are tidal disturbances: disks warped, bursts of star formation from gas compression, and the eventual settling into a larger, more spheroidal galaxy. Whether the Sun or Earth will survive intact depends on the Sun’s remaining lifetime and chaotic orbital changes, but direct physical destruction by stellar collisions is not expected.

Satellites, observations and why Andromeda matters

Andromeda acts as a nearby laboratory: it has a rich system of satellites, visible stellar streams that record past mergers, and a long history of observations from ground and space. Because it’s close enough to resolve individual stars in many parts, M31 lets astronomers test galaxy‑formation models and compare those results directly with our own Milky Way.

9. Hosts many satellite galaxies — M32, M110 and dozens more

Andromeda has a population of several dozen identified satellite galaxies, ranging from the compact, bright ellipticals M32 and M110 to numerous faint dwarf companions discovered by surveys like Pan‑STARRS and PAndAS. These satellites orbit within Andromeda’s dark matter halo and are prime targets for studies of dwarf galaxy evolution.

Stellar streams detected in Andromeda’s halo are fossil records of past accretion events, where smaller galaxies were torn apart and incorporated into the halo. Mapping satellites and streams helps astronomers trace the galaxy’s growth history and infer the shape and extent of its dark matter distribution.

10. A cornerstone object for telescopes and cosmology

As one of the best‑known facts about the Andromeda Galaxy shows, M31 played a decisive role in showing that “island universes” exist beyond the Milky Way: Edwin Hubble’s Cepheid work around 1923–1924 settled a century‑long debate. Since then, instruments from the Hubble Space Telescope to GALEX, ground‑based surveys, and, more recently, JWST imaging campaigns have produced detailed maps across wavelengths.

Andromeda continues to shape cosmology and galaxy science: it helps calibrate the extragalactic distance ladder, provides a nearby example to test galaxy‑formation simulations, and supplies striking images that engage the public and inspire future observers. Because it’s both accessible and complex, M31 remains central to extragalactic astronomy.

Summary

- M31 is Messier 31 and a major Local Group member with roots in observations from al‑Sufi (964 AD) through Messier (1764) to Hubble’s Cepheid work in the 1920s.

- It lies about 2.5 million light‑years away yet is visible to the naked eye under dark skies (apparent magnitude ≈3.4), illustrating how nearby in cosmological terms our neighborhood is.

- Andromeda is large—roughly 220,000 light‑years across with an estimated ~1×10^12 stars—and hosts a central black hole of order 100–200 million solar masses.

- It is approaching the Milky Way at about 110 km/s, with simulations predicting a first close encounter in ~4–5 billion years and an eventual merger into a larger, more spheroidal system.

- Because of its satellites, stellar streams, and long observation history (from Hubble to JWST), Andromeda remains a cornerstone for calibrating distances, testing galaxy models, and inspiring observers—so take a pair of binoculars this autumn and look for that faint, ancient smudge.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.