On February 15, 2013, a meteor exploded over Chelyabinsk, Russia, sending a shock wave that shattered windows across the city and injured about 1,500 people — a vivid reminder that space rocks can affect everyday life with almost no warning (NASA summary). That single event and a string of close calls since have pushed planetary defense from a niche science into a practical public-safety concern.

This article walks through ten of the closest, most surprising, or most consequential near-misses and last-minute detections: very close passes, surprise detections and airbursts, and high-profile prediction scares. For each item I give dates, sizes, measured distances where available (using NASA/JPL and peer-reviewed studies), who caught the object, and what the event taught us about surveying, follow-up, and response. The takeaway: the near-Earth environment is busy, detection is improving, but gaps remain.

Very Close Approaches: When Space Rocks Came Scarily Near

1. 2020 QG — The closest recorded non-impacting flyby

On August 16, 2020, asteroid 2020 QG passed astonishingly close to Earth — roughly 2,950 kilometres above the surface, according to JPL’s close-approach data (JPL Small-Body DB).

The object was tiny, only a few metres across (estimates put it at roughly 3–6 m), and it was discovered only after it had already slipped past our planet. Had it been much larger, a flyby at that altitude would have posed a real threat to low-orbit satellites and to human-made infrastructure in low Earth orbit.

2020 QG underlined a basic limit: ground-based surveys routinely miss the smallest, fastest-moving objects until after close approach. That gap has driven investment in wider-field surveys and faster processing so more sub-10-m objects are caught before they pass (or, at least, before they hit).

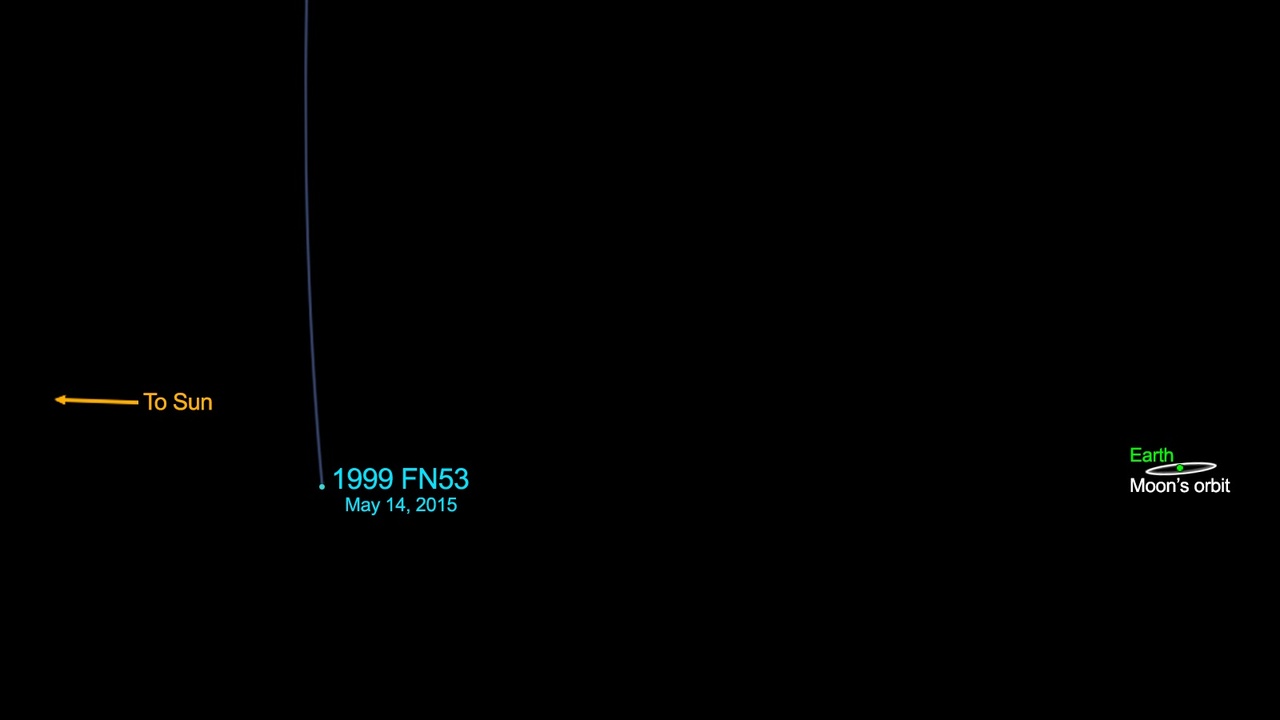

2. 2012 DA14 — A close shave with geosynchronous space

Asteroid 2012 DA14 made headlines on February 15, 2013 when it passed about 27,700 kilometres above Earth’s surface — well inside the altitude of geostationary satellites (≈35,786 km) (JPL).

Estimates put 2012 DA14 at roughly 45–50 metres across. Observatories tracked it closely in the days before and after closest approach, and the near-simultaneous Chelyabinsk airburst that same day amplified public alarm by showing two different risks: a relatively large tracked flyby and an unrelated, untracked airburst from a smaller object.

That coincidence spurred clearer messaging about what surveys can and can’t do, and it highlighted the real vulnerability of satellites in certain altitudes to unexpectedly close passes.

3. 2019 OK — A surprise discovery days before a close pass

Discovered only a few days before its July 2019 close approach, 2019 OK alarmed astronomers because it arrived from a part of the sky less well covered by surveys. At closest approach it passed at a distance on the order of tens of thousands of kilometres (JPL lists the precise close-approach data), and observers estimated its size in the tens of metres.

The short discovery lead time — days, not months or years — showed how gaps in southern-hemisphere and twilight survey coverage can leave blind spots. After 2019 OK, survey operators emphasized faster follow-up and pushed for more all-sky coverage so similar objects are found earlier.

Surprises That Hit or Nearly Did: Short-Notice Detections and Airbursts

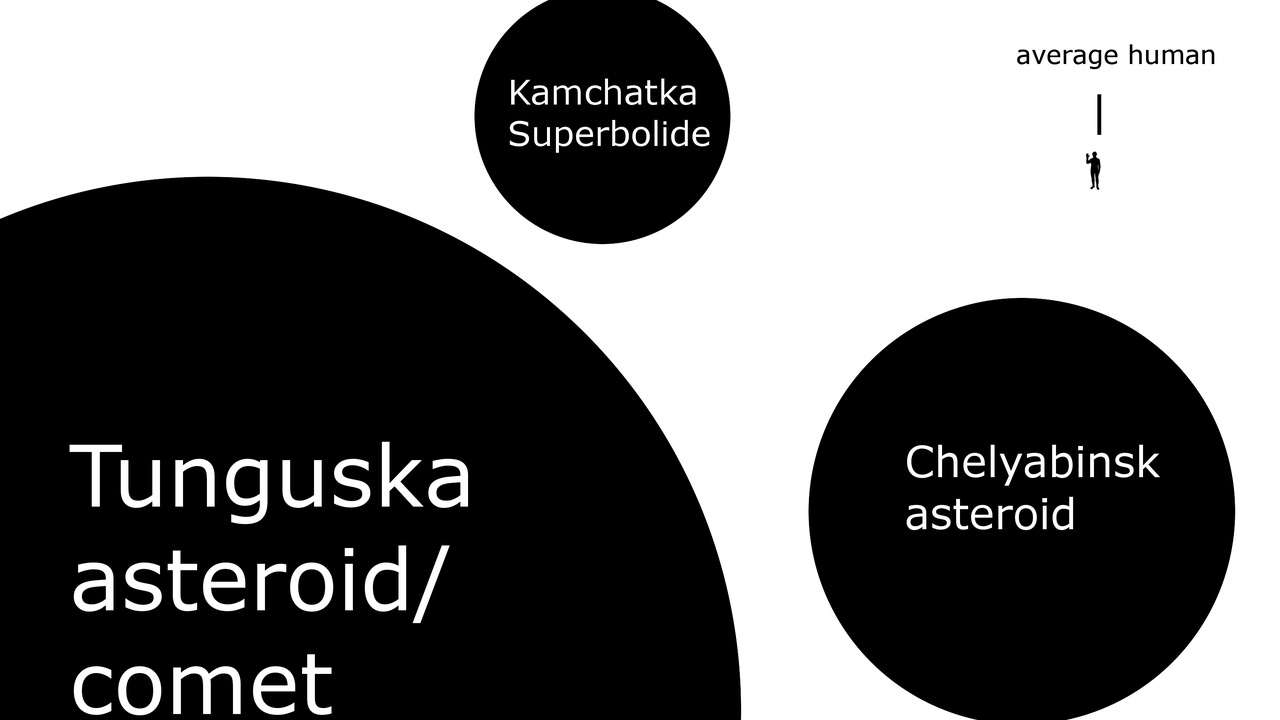

4. Chelyabinsk (2013) — A powerful wake-up call

On 15 February 2013 a roughly 20-metre asteroid detonated over Chelyabinsk, Russia, producing an airburst with an estimated energy on the order of a few hundred kilotons of TNT and injuring about 1,500 people, mostly from broken glass (NASA; peer-reviewed analyses provide similar yield ranges).

Video from dashcams allowed scientists to triangulate the trajectory and energy release precisely, revealing how a relatively small object can cause widespread local damage. That event accelerated investment in atmospheric monitoring (infrasound networks and satellite detection) and public messaging about what to do during bright fireball events.

5. 2008 TC3 — The first asteroid predicted to hit Earth

On October 7, 2008 astronomers detected 2008 TC3 about 20 hours before it entered Earth’s atmosphere above northern Sudan — the first time an impact was predicted in advance and meteorites were later recovered (JPL).

At only a few metres across, the object broke up in the atmosphere, but coordinated tracking and rapid ground searches recovered fragments (the Almahata Sitta meteorite). That recovery yielded valuable samples whose pre-impact orbit was known, teaching researchers about asteroid composition and fragmentation.

6. 2018 LA — Hours of warning, then a harmless fall

2018 LA was discovered just hours before it entered Earth’s atmosphere on June 2, 2018. The rock was only a few metres across and produced a fireball over southern Africa; small fragments were later reported in the region (JPL).

Events like 2018 LA show that the system for finding metre-scale impactors is working in principle — objects are sometimes detected before entry — but the warning window for local authorities and the public is measured in hours, not days.

Prediction Scares and False Alarms: When Calculations Overstated the Danger

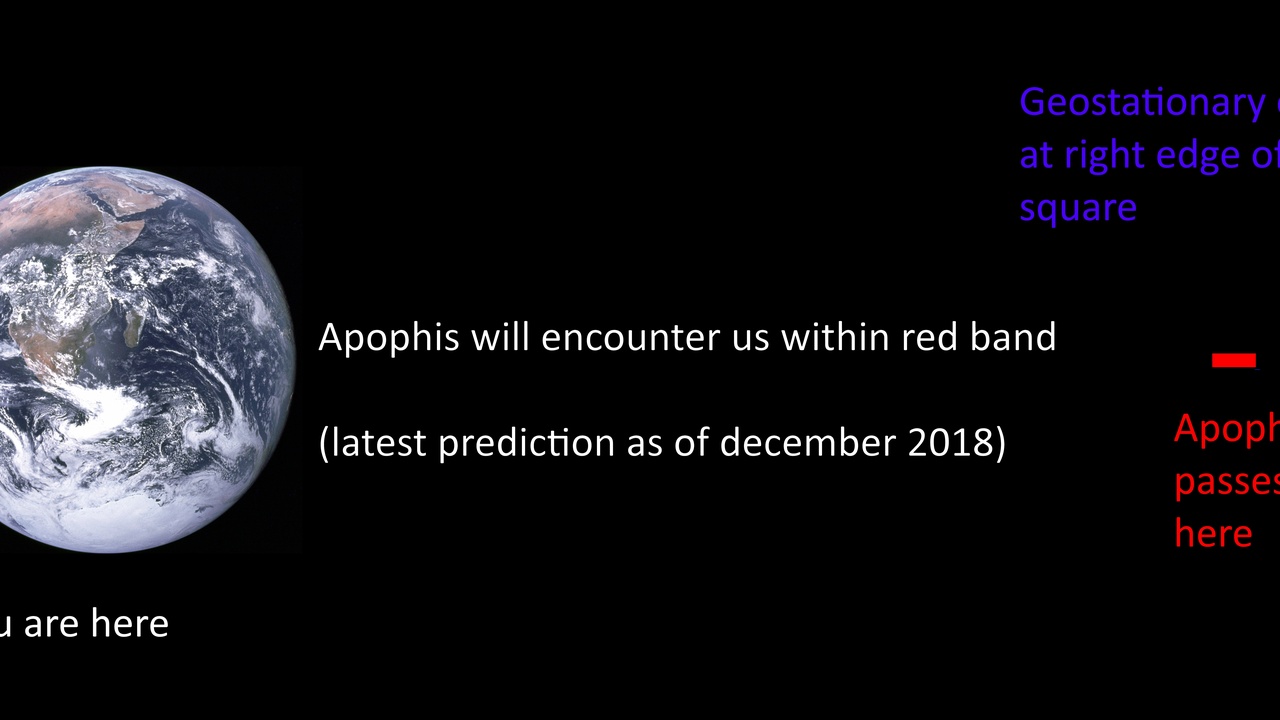

7. 99942 Apophis — From headline risk to a well-studied close pass

Discovered in 2004, Apophis briefly carried a non-negligible impact probability in early orbit solutions that drew intense media attention. Follow-up observations quickly refined the orbit and removed an immediate impact risk (JPL).

Apophis will make a well-observed close approach on April 13, 2029. Current orbital solutions place that flyby at approximately 31,600 kilometres above Earth’s surface, a distance close enough to interest satellite operators and to teach scientists about gravitational “keyholes” that can alter future impact probabilities.

The Apophis saga shows how early uncertainty can create alarming headlines, and why rapid, coordinated observations are essential to turn initial probabilities into reliable forecasts.

8. 1997 XF11 — Early orbit uncertainties and public alarm

In the late 1990s initial orbital elements for 1997 XF11 produced headlines suggesting a possible close approach decades ahead. Additional observations lengthened the observation arc and the perceived risk fell to zero; the object was never a serious impact threat once more data were added.

Technically this illustrates a simple point: short observation arcs create large orbit uncertainties, and early impact probabilities can be misleading unless communicated with care. The IAU and NASA refined public messaging after cases like this to avoid unnecessary panic.

9. 2002 NT7 and similar early scares — Why surveys matter

2002 NT7 is one of several objects whose early risk estimates (based on limited data) suggested a non-zero chance of impact before later observations cleared them. Cases like NT7 motivated the development of automated risk pages (NASA Sentry, ESA risk pages) and stronger protocols for rapid follow-up.

Those procedural and software improvements helped reduce false alarms and focus attention on genuinely threatening objects, a concrete benefit for both scientists and policymakers as survey cadence and processing speed have increased.

What These Near-Misses Teach Us About Planetary Defense

The ten stories above point to four practical lessons. First, global, continuous survey coverage — including the southern hemisphere and twilight skies — is essential to catch objects like 2019 OK earlier (programs such as Pan-STARRS and ATLAS have already made huge gains, and the upcoming Vera Rubin Observatory will increase discovery rates dramatically).

Second, rapid follow-up and orbit refinement reduce false alarms and let authorities plan. Automated systems (NASA’s Sentry, ESA’s risk pages) plus coordinated ground-based follow-up sharpen predictions within hours to days.

Third, even small objects can matter. Chelyabinsk (~20 m, ~1,500 injured) showed that airbursts can injure people and damage buildings, so infrasound networks, satellite bolide detection, and local emergency plans must be part of preparedness.

Finally, investment in mitigation testing and international cooperation matters. The DART mission (NASA, a kinetic deflection test) and the establishment of NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office are examples of progress, but sustained funding for surveys, follow-up networks, and data-sharing will keep reducing the chance that earth almost got hit by asteroid events turn into disasters.

10. Lessons learned and concrete policy steps

The bottom-line actions are straightforward: expand survey coverage in the southern hemisphere, accelerate automated follow-up and data sharing, strengthen atmospheric monitoring (infrasound and space-based infrared), run emergency-response drills for local airbursts, and sustain international collaboration on response plans.

Programs to watch include Pan-STARRS and ATLAS (operational survey networks), the Vera Rubin Observatory (coming online to increase discovery rates), DART (an active mitigation test), and the NASA Planetary Defense Coordination Office (which coordinates U.S. civil response). Supporting those efforts is the clearest practical way to reduce future risk.

Summary

- Close approaches can be extremely close — some objects (e.g., 2020 QG) have passed only a few thousand kilometres above Earth.

- Small rocks cause real harm: Chelyabinsk (~20 m) injured ~1,500 people and broke glass across a city.

- Improved surveys, faster follow-up, and international data-sharing reduce false alarms and give authorities time to act.

- Keep supporting planetary defense programs and public-warning systems so future earth almost hit by asteroid scares are detected earlier and managed more effectively.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.