Some permanently shadowed lunar craters can drop below 25 K (−248 °C), making parts of the Moon colder than Pluto on a good day.

Those extremes matter: ultra-cold spots trap water and volatile ices for geologic time, preserve chemical fingerprints of the early solar system, and create stubborn engineering problems for landers and rovers. Scientists map these temperatures with a mix of direct radiometry, occultations, and flyby instruments so we can understand where volatiles survive and why.

This article tours the 10 coldest places in solar system, explaining why each locale is so frigid, how temperatures were measured, and what those cold traps teach us about planetary history and exploration. The list spans four groups: distant dwarf planets and Kuiper Belt objects, icy moons of the giant planets, cold layers in giant-planet atmospheres, and permanently shadowed night-side pockets close to home.

Icy Dwarf Planets and Trans‑Neptunian Objects

Far from the Sun, a high surface albedo plus tiny or no atmosphere drives equilibrium temperatures down to a few tens of kelvin. Observers estimate surface temperatures using thermal infrared radiometry (Spitzer, Herschel), occultation-derived sizes and albedos, and flyby radiometers like New Horizons’ instruments on Pluto.

1. Eris (dwarf planet) — extremely low equilibrium temperature

Eris is one of the coldest known solar-system surfaces because it sits far beyond Neptune and is extraordinarily bright. At times it lies past ~96 AU and, with an estimated geometric albedo near 0.96, absorbs very little sunlight.

Thermal modeling and Herschel/Spitzer measurements put Eris’s characteristic surface temperatures at roughly 30–50 K (−243 to −223 °C), depending on assumed emissivity and local terrain. Those low temperatures help preserve volatile ices such as methane and nitrogen over billions of years, so Eris is a key data point for models of outer‑system chemistry and volatile retention.

2. Pluto (dwarf planet) — frigid nitrogen plains and night-side lows

New Horizons’ 2015 flyby gave the first direct thermal and albedo maps of Pluto, revealing bright nitrogen-ice regions (Tombaugh Regio) and strong day–night contrasts.

Measured surface temperatures vary by region and season, typically in the ~33–55 K range (−240 to −218 °C). New Horizons’ Ralph and radiometry data, combined with Earth-based infrared studies, show nitrogen and methane ices that can sublimate, condense, and drive seasonal atmosphere collapse at far points in Pluto’s orbit.

3. Makemake and other bright Kuiper Belt objects

Makemake and similar KBOs sit beyond Neptune and often display bright, methane-rich surfaces that reflect much of the sunlight they receive. Thermal infrared observations from Spitzer and Herschel plus occultation-based size/albedo constraints put many of these objects in roughly the 30–50 K range (−243 to −223 °C).

Because they retain primordial ices, these bodies are natural laboratories for understanding early solar-system composition and for testing how small bodies hold or lose volatiles over time.

4. Sedna and detached extreme trans‑Neptunian objects

Sedna follows a very elongated orbit that leaves it tens to hundreds of AU from the Sun for long stretches, so its equilibrium temperature is extremely low. Direct thermal detections are challenging because the thermal signal is faint, so temperature estimates rely on models and sparse photometry.

Typical model-based values suggest surface temperatures often below ~40 K (−233 °C), though uncertainties are large. Sedna-like objects are valuable because they likely preserve ancient ices and record the dynamical history of the solar system’s outermost regions.

Icy Moons of Giant Planets

Large satellites around Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune are chilled by solar distance and by icy surface materials. In many cases a thin or transient atmosphere, sublimation cooling, and shadowed local terrain lower temperatures further. Spacecraft flybys and orbital infrared mapping revealed both global cold and localized hot spots.

5. Triton (Neptune’s largest moon) — nitrogen ice and cryovolcanism in the cold

Triton ranks among the coldest large moons observed. Voyager 2’s 1989 flyby showed extensive nitrogen frost, cantaloupe terrain, and active geyser-like plumes driven by subsurface heating beneath a frigid surface.

Voyager-era thermal estimates place Triton’s surface in the ~30–40 K range (−243 to −233 °C). Low temperatures let nitrogen behave as a surface volatile, enabling seasonal transport and exotic cryovolcanic processes that hint at internal heat despite the cold exterior.

6. Enceladus (Saturn) — cold surface, warm interior

Enceladus has a very cold global surface but surprising localized warmth at the south‑polar “tiger stripes.” Cassini’s thermal infrared mapping found typical surface temperatures from roughly 35 K in the sunlit, high‑latitude areas up to tens of kelvin warmer on the tiger stripes (localized anomalies).

Cassini also flew through the plumes and sampled salt-rich ice grains and organics, showing the scientific payoff when cold preservation meets internal habitability potential. The cold exterior preserves organics while internal heat powers ongoing plume activity.

7. Miranda (Uranus moon) and other small, heavily cratered satellites

Uranian moons like Miranda are extremely cold because they sit far from the Sun and receive little tidal heating. Voyager 2’s 1986 flyby provided the only close-up views for many of these bodies, showing heavily cratered and patchy terrains.

Estimated surface temperatures for these small satellites often fall below ~50–60 K (−223 to −213 °C). Those low temperatures lock in ancient impact records and limit volatile mobility, so the surfaces are time capsules of collisional history.

Giant Planet Atmospheres and Polar Regions

Coldness isn’t limited to solid surfaces. Upper-atmosphere layers and polar regions on the giant planets can reach very low temperatures due to radiative balance, composition, and, in some cases, low internal heat flux.

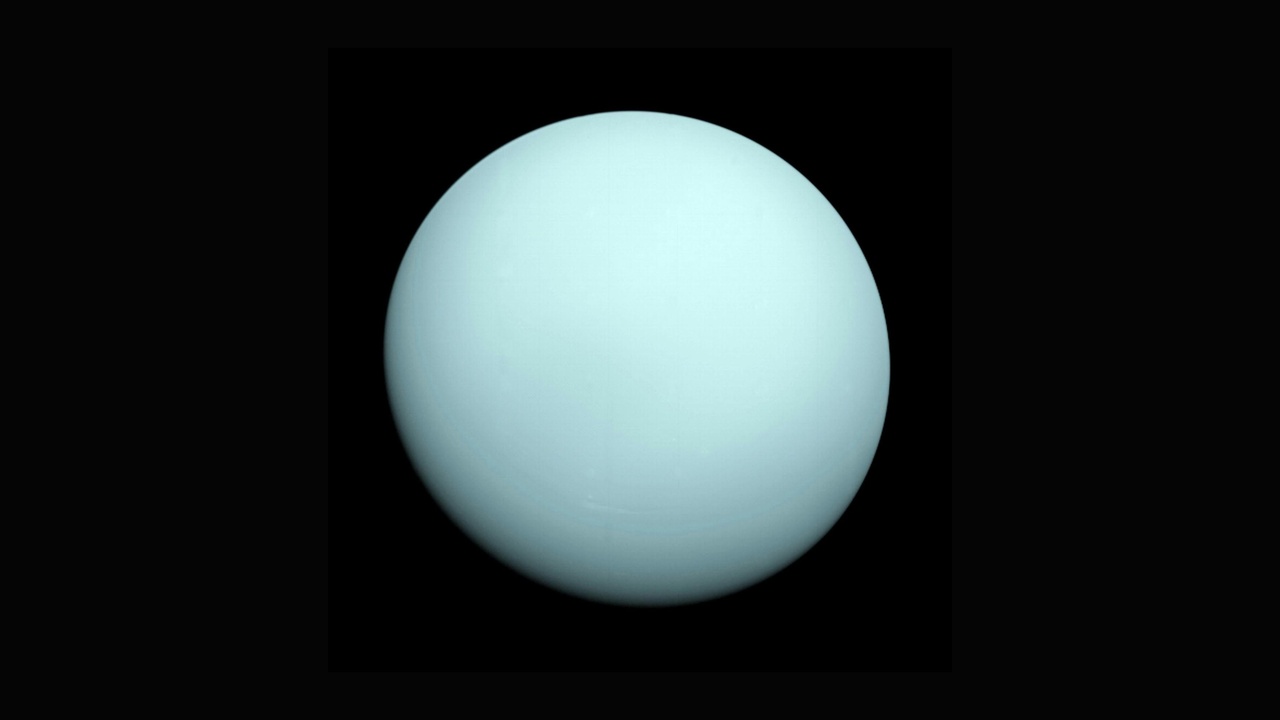

8. Uranus’s upper atmosphere — the coldest planetary atmosphere measured

Voyager 2 radio‑occultation profiles showed Uranus has the coldest measured planetary atmosphere among the classical planets, with tropopause temperatures on the order of ~49 K (−224 °C) and colder regions higher up in the atmosphere.

Uranus’s unusually low internal heat flux compared with Neptune, plus seasonal effects from its extreme axial tilt, help explain the chill. Those low atmospheric temperatures change cloud condensation levels and photochemistry, producing a very different climate from its ice-giant neighbor.

9. Neptune’s upper atmosphere and unexpected cold pockets

Neptune emits more internal heat than Uranus, yet Voyager 2 and later submillimeter/infrared studies found complex vertical temperature structure with surprisingly cold mesospheric or thermospheric layers in places. Some retrievals show local minima in the ~50–70 K range (−223 to −203 °C), depending on altitude and composition.

Wave dynamics, radiative cooling by hydrocarbons, and variable energy deposition can create these cold pockets. Studying them helps scientists balance energy budgets and explain observed cloud activity and wind patterns.

Permanently Shadowed Regions and Night Sides

Permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) near polar poles and deep night-side hollows are among the coldest accessible spots in the inner solar system because sunlight never reaches them. Orbital radiometers and neutron spectrometers reveal temperatures that can rival or beat those in the outer solar system.

10. Permanently shadowed craters (Moon, Mercury) — local absolute cold traps

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter’s Diviner instrument measured near-surface temperatures in some lunar PSRs down to around 25 K (−248 °C), making those spots the coldest directly measured near-surface locales in the solar system.

MESSENGER mapped Mercury’s poles and found narrow, permanently shadowed hollows cold enough to trap water ice despite the planet’s proximity to the Sun. LCROSS’s impact into Cabeus (2010) detected water/ice signatures, and MESSENGER’s neutron spectroscopy confirmed volatile deposits in polar craters.

PSRs store water, organics, and other volatiles for billions of years and are prime targets for in‑situ resource use and science; they also pose thermal-design challenges for landers that must survive extremely cold, sunless environments.

Summary

- Cold extremes come in four flavors: distant icy worlds, frozen moons, frigid atmospheric layers, and permanently shadowed pockets—each probed by missions like New Horizons, Voyager 2, Cassini, Herschel/Spitzer, LRO/Diviner, MESSENGER, and LCROSS.

- Some lunar PSRs (≈25 K) are colder than many distant dwarf planets; conversely, Uranus holds the record for the coldest measured planetary atmosphere (Voyager 2 radio‑occultation profiles).

- Measurement techniques—thermal radiometry, occultations, radio occultations and in‑situ plume sampling—are critical to convert remote brightness into real temperatures and to understand volatile behavior.

- These extremely low-temperature locales preserve ices and organics, record solar-system history, and shape future exploration priorities from ISRU on the Moon to proposed missions to Uranus and Neptune.

- New maps of the coldest places in solar system from future missions and long-term monitoring will refine temperature estimates and help decide where to send landers and sample-return missions.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.