In 1609 Galileo pointed a simple refracting telescope at Jupiter and saw its four largest moons, a sight that helped dethrone an Earth-centered universe. Fast forward to 2022 when the James Webb Space Telescope returned infrared images of galaxies and stellar nurseries with detail that would have been unimaginable to Galileo’s contemporaries.

Those two moments bookend four centuries of innovation. A handful of engineering and computational advances repeatedly expanded what telescopes can detect, resolve, and measure, and many of those advances spun off into everyday tech — from GPS timing to medical imaging. This article lays out the ten breakthroughs that most reshaped professional astronomy and widened public access to the sky, organized into optical/mirror engineering, detectors and instruments, space- and radio-based methods, and the computing and data systems that turn raw signals into discovery.

Optical and Mirror Advances

Improvements in mirror design and optical engineering increased aperture, corrected distortion, and reduced mass and cost, directly boosting light‑gathering and resolving power. Segmented primaries and adaptive optics emerged as foundational milestones (Keck first light 1993; major AO demos in the 1990s), enabling ground telescopes to probe much fainter and finer detail.

1. Adaptive optics and atmospheric correction

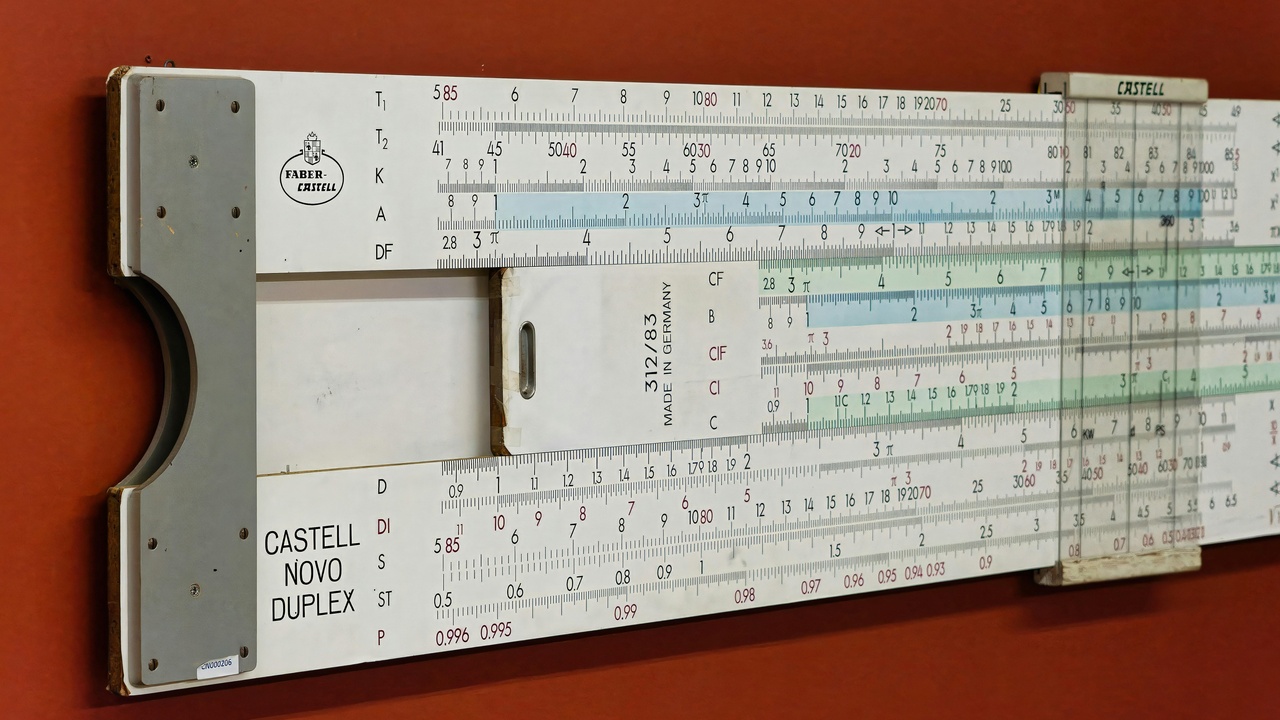

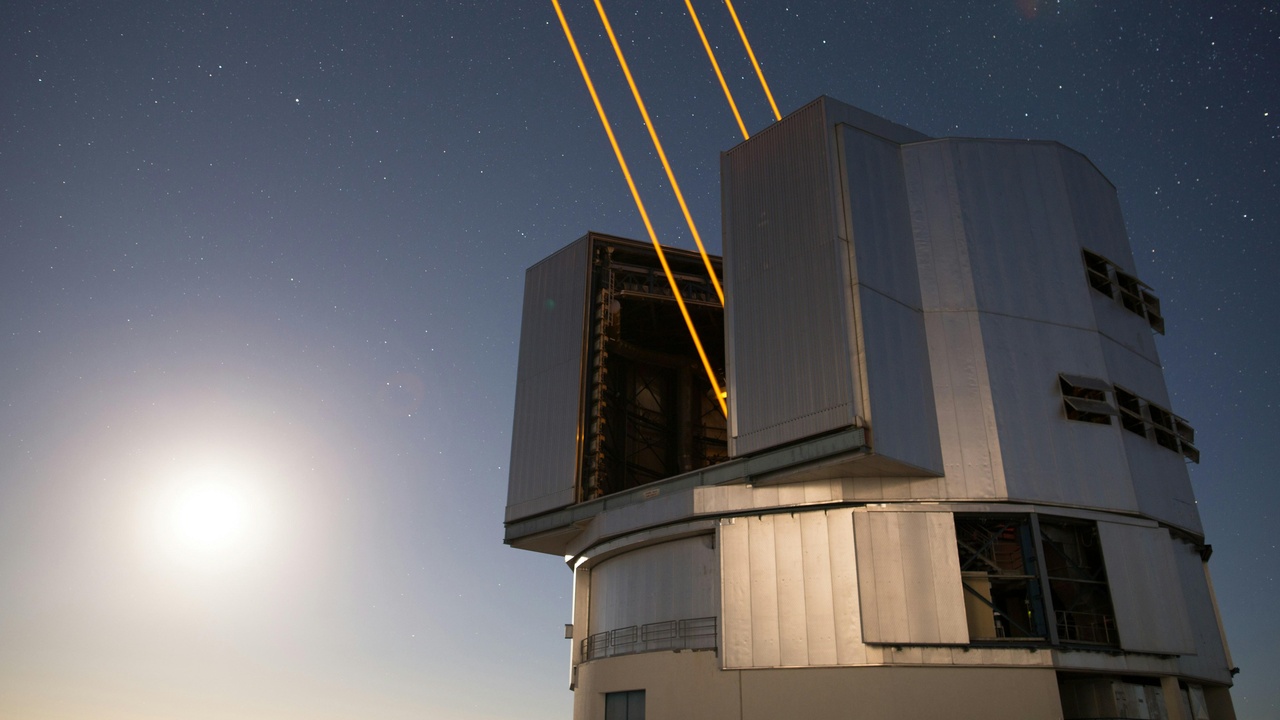

Adaptive optics (AO) measures atmospheric turbulence in real time with wavefront sensors and corrects it using deformable mirrors, sharpening ground-based images toward the telescope’s diffraction limit. Early astronomical AO experiments began in the late 1980s, with routine, science‑grade systems appearing on Keck, the VLT, and Gemini in the 1990s–2000s.

Quantitatively, AO can improve resolution by factors of roughly 5–10 compared with uncorrected seeing on 8–10 m telescopes, delivering angular resolution near the theoretical diffraction limit in the near‑IR. That jump made direct imaging of exoplanets and precise astrometry possible from the ground.

Practical outcomes include Keck AO’s imaging of the Galactic Center beginning in the late 1990s and 2000s, which tracked stellar orbits around Sgr A* to infer the central black hole’s mass, and the Gemini South GeMS multiconjugate AO system that yields uniform correction over larger fields. ESO’s AO suite on the VLT similarly transformed studies of crowded star fields and protoplanetary disks.

2. Segmented primary mirrors

Segmented mirrors allow a single optical surface to be built from many smaller pieces, scaling apertures far beyond what’s feasible with monolithic glass. The W. M. Keck Observatory achieved first light in 1993 with a 10‑m primary made of 36 hexagonal segments.

Modern extremely large telescopes follow the same idea: the Giant Magellan Telescope uses seven 8.4‑m segments, the Thirty Meter Telescope design calls for ~492 segments, and ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope plans a 39‑m primary composed of 798 segments. Edge sensors and actuators actively phase the segments to nanometer precision so the array behaves like a single, continuous mirror.

The result is vastly increased light‑gathering power and the ability to take spectra of very faint, high‑redshift galaxies and to measure tiny spectral signatures in exoplanet atmospheres.

3. Lightweight mirrors, advanced coatings, and active support

Material and structural advances cut mirror mass and improved optical stability. Low‑expansion substrates like Zerodur and ULE, and stiff, lightweight materials such as silicon carbide, allowed larger space and ground mirrors without prohibitive weight.

Honeycomb and meniscus backings can reduce blank mass by 50% or more versus solid glass, easing handling and lowering thermal inertia. Coating technology also evolved: protected silver and dielectric stacks boost infrared reflectivity, while enhanced aluminum remains common for UV/visible bands, often improving reflectivity by several percentage points across targeted wavelengths.

Herschel’s 3.5‑m silicon carbide primary (launched 2009) exemplifies alternative substrates used in space, and active support systems keep large ground mirrors figure‑accurate under gravity and temperature changes.

Detector and Imaging Breakthroughs

Improved detectors transformed telescopes from visual instruments into sensitive, quantitative photometers and spectrographs. From the invention of the CCD to superconducting sensors and cryogenic IR arrays, detector advances raised quantum efficiency, cut noise, and widened accessible wavelengths for astronomy.

4. Charge-coupled devices (CCDs) and digital imaging

CCDs, invented by Willard Boyle and George E. Smith at Bell Labs in 1969, replaced slow, nonlinear photographic plates with efficient, linear digital detectors. Astronomy began adopting CCDs widely in the 1970s and 1980s and by the 1990s they were standard for imaging surveys and precision photometry.

Where plates converted only ~1–2% of incoming photons into a measurable signal, scientific CCDs routinely achieved 70–90% quantum efficiency in visible bands, with far better linearity and lower noise. That jump enabled millimagnitude transit photometry for exoplanet detection, deep imaging surveys like the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, and a boom in amateur CCD astronomy.

5. Infrared detectors and cryogenic systems

Infrared detectors and their cryogenic housings opened windows through dust and to the high‑redshift universe. Space missions and ground instruments extended sensitivity across 1–30+ μm bands by combining low‑noise detector materials with cooling to tens of kelvin or below.

Spitzer launched in 2003 and provided transformative IR surveys; JWST launched in 2021 and returned first science images in 2022, with NIR detectors operating around a few tens of kelvin and MIRI cooled to roughly 7 K. Cryocoolers, low dark‑current readouts, and careful thermal design reduced thermal noise sufficiently to detect faint, dusty galaxies and molecular signatures in exoplanet atmospheres.

On the radio/submm side, ALMA’s superconducting SIS mixers and cryogenic receivers dramatically improved sensitivity in the (sub)millimeter bands for star‑formation and chemistry studies.

6. Integral field spectroscopy and advanced imaging instruments

Integral field units (IFUs) capture a spectrum at every point across a two‑dimensional field, turning images into datacubes in a single exposure. IFUs revolutionized studies of galaxy kinematics, resolved stellar populations, and gas flows.

MUSE on the VLT, for example, delivers a ~1′×1′ field with spectral resolutions of a few thousand, producing spatially resolved velocity and chemical maps of galaxies. Other advances — AO‑fed spectrographs and photon‑counting arrays such as MKIDs — improved sensitivity for faint, fast, or crowded targets, enabling time‑domain and exoplanet atmosphere work.

Space-Based and Radio Telescope Innovations

Putting telescopes above the atmosphere or linking antennas across continents enabled observations impossible from a single ground site. Space telescopes opened blocked wavelengths, while interferometry and radio arrays reached resolutions from sub‑arcsecond down to micro‑ and nanoarcsecond scales.

7. Space telescopes: escaping the atmosphere

Space observatories avoid atmospheric absorption and turbulence, granting access to UV, X‑ray, and far‑IR bands and permitting long, stable exposures. Hubble (launched 1990) transformed optical and UV astronomy — its Deep Field (1995) revealed thousands of faint galaxies in a tiny patch of sky. Chandra (launched 1999) and XMM‑Newton unlocked high‑energy phenomena, while Spitzer and later JWST extended deep IR sensitivity.

JWST, with first images in 2022, pushes deeper in the infrared than Hubble by several magnitudes in its bands, revealing candidate galaxies at very high redshift and detailed structure in protoplanetary disks. Space platforms also deliver stable point‑spread functions and uninterrupted exposures that are critical for precision photometry and faint‑object spectroscopy.

Discoveries enabled by space telescopes include the accelerating expansion measured with supernova surveys, detailed studies of galaxy formation, and direct spectroscopy of exoplanet atmospheres.

8. Radio interferometry and very long baseline arrays

Linking multiple radio antennas converts their separation into effective aperture, producing dramatically improved angular resolution. Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) matured through the late 20th century, and arrays like ALMA began early science in 2011 with baselines up to ~16 km for submillimeter work.

The Event Horizon Telescope combined radio dishes across continents (2017 observations) and, after petabyte‑scale data correlation, produced the first horizon‑scale image of M87’s black hole in 2019. VLBI routinely achieves microarcsecond astrometry for pulsars, masers, and proper‑motion studies, letting astronomers map jets and measure distances with exquisite precision.

These techniques also underpin geodesy and precise Earth‑rotation measurements, demonstrating practical spin‑offs beyond astrophysics.

Computing, Data, and Access: Algorithms to Citizen Science

These breakthroughs in telescope technology also depend on software, algorithms, and open data to convert raw signals into discoveries. High‑performance computing, automated pipelines, and public archives have turned huge data streams into usable science and broadened who can contribute.

9. High-performance computing, image reconstruction, and algorithms

Complex, sparse measurements require advanced correlation and reconstruction to yield images and spectra. The Event Horizon Telescope collected petabytes of raw radio data in 2017, physically shipping hard drives to correlation centers where distributed processing produced the 2019 M87 result.

Algorithms from CLEAN deconvolution to compressed sensing and machine learning are now standard for removing artifacts, recovering faint features, and detecting transients. Survey pipelines run on GPU‑accelerated clusters or cloud HPC to process terabytes or petabytes of data; for interferometry, correlation and imaging can take days to weeks depending on baseline complexity.

Signal‑processing techniques developed for astronomy have found use in medical imaging, remote sensing, and telecommunications, highlighting the broader impact of algorithmic progress.

10. Open data, survey telescopes, and citizen science

Public data releases and wide‑field surveys democratized discovery. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey began public releases in the early 2000s and cataloged hundreds of millions of objects, powering thousands of papers and enabling cross‑disciplinary research.

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory (LSST) is expected to begin full survey operations in the mid‑2020s, producing roughly ~20 TB of raw data per night and delivering rapid alerts for transient events. Platforms like Zooniverse let volunteers identify rare objects and patterns; several citizen‑led findings have progressed to peer‑reviewed publications.

Together, open archives, automated alert streams, and engaged volunteers accelerate follow‑up of near‑Earth asteroids, supernovae, and unusual variable sources, expanding both professional and public contribution to astronomy.

Summary

- Optical engineering (segmented mirrors, lightweight substrates) and AO let ground telescopes reach resolutions and sensitivities once possible only from space.

- Detectors — CCDs, cryogenic IR arrays, and superconducting receivers — multiplied quantum efficiency and extended coverage from UV to submillimeter bands.

- Space observatories and interferometric arrays opened blocked wavelengths and achieved horizon‑scale or microarcsecond resolution when paired with powerful reconstruction algorithms.

- High‑performance computing, open surveys, and citizen science transformed raw data into rapid discoveries, showing that software and access are as transformative as hardware.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.