In 1960, Frank Drake pointed a radio dish at two nearby stars and conducted the first modern search for extraterrestrial intelligence. That quiet experiment launched a field.

SETI matters because it pushes astronomy into new directions and asks one of the oldest questions people can imagine: are we alone? The effort has driven improvements in telescope hardware, sparked novel computing techniques, and pushed astronomers to craft testable hypotheses about signatures of technology beyond radio waves.

Over six decades, work that began with a single dish has grown into coordinated surveys, petabyte datasets, and new theory. These 10 breakthroughs in seti research track how instruments, data, and institutions together reshaped the search for intelligent life.

Along the way there have been surprises: Breakthrough Listen began in 2015 and immediately changed expectations about data volume and openness. That launch is one of several turning points covered below.

Technological Advances Driving Detection

1. Development of large radio arrays and dedicated SETI instrumentation

Larger collecting area and more simultaneous beams translate directly into sensitivity and survey speed. For radio work, that means arrays of many dishes combined by aperture synthesis rather than a single huge dish.

Facilities such as the Very Large Array (27 dishes) demonstrate how aperture synthesis yields high sensitivity and resolution. The Allen Telescope Array was designed around the concept of commensal SETI observing (an eventual 42-dish design) so surveys could run alongside other science.

Pathfinders for the Square Kilometre Array are pushing both raw sensitivity and wide-band receivers. The practical payoff: the ability to detect much weaker transmitters at greater distances, to survey larger sky areas in less time, and to dedicate backends that maximize SETI observing efficiency.

2. Advanced signal processing and machine learning for sifting data

Modern receivers produce wide instantaneous bandwidths, and that creates terabytes per observing session. Processing that stream by hand no longer works; pipelines and machine learning now shoulder the load.

Breakthrough Listen, launched in 2015, generated petabyte-scale datasets and prompted development of matched-filter searches, convolutional neural networks, and automated candidate ranking. These tools cut human vetting time and improve rejection of radio-frequency interference (RFI).

Convolutional classifiers spot subtle narrowband patterns in noisy backgrounds. Automated RFI flagging at major observatories preserves valuable observing time and lets teams reprocess archival data with ever-better algorithms.

3. Optical SETI and fast-transient searches broaden the search space

Radio isn’t the only channel worth watching. Optical SETI looks for short, powerful laser pulses; infrared searches seek waste-heat signatures. Fast-transient astronomy forced a rethink about ephemeral technosignatures.

Fast Radio Bursts first entered the literature with the 2007 Lorimer burst. Since 2018, CHIME has found many FRBs and shown how wide-field, high-cadence surveys can reveal unexpected phenomena. That success feeds directly into strategies for catching short-lived technosignatures.

Targeted laser-pulse searches at nearby stars and coordinated transient follow-ups across radio and optical facilities expand the kinds of detectable technology. Cross-wavelength work increases confidence when unusual signals appear.

Observational Strategies and Survey Design

4. All-sky surveys and volunteer computing expanded processing capacity

Distributed computing and automated all-sky surveys multiplied both processing power and sky coverage. SETI@home, launched in 1999, mobilized millions of volunteers and their PCs to analyze radio data.

Today, cloud clusters and HPC facilities supplement volunteer efforts and enable reprocessing of archival datasets with new algorithms. Automated pipelines can scan archived telescope data continuously and flag rare events for human review.

The outcome is simple: massively increased CPU resources, steady reanalysis of older observations, and a higher likelihood of catching transient or rare signals that single-pass surveys would miss.

5. Targeted searches of exoplanetary systems sharpened priorities

Exoplanet surveys changed SETI from a blind hunt to a targeted science. As of 2024, space missions have confirmed more than 5,000 exoplanets, letting researchers prioritize Earth-size and habitable-zone worlds.

Observing a star during a planetary transit or focusing on known multiplanet systems (TRAPPIST-1, for example) can improve signal-to-noise for some hypothetical technosignatures. Telescope time is scarce; prioritization matters.

Teams now submit proposals requesting time on instruments such as the Green Bank Telescope or Parkes specifically to monitor high-probability targets informed by Kepler and TESS catalogs.

6. Multi-messenger and rapid-response observing improved follow-up

Coordinated observations across wavelengths and facilities make follow-up faster and more decisive. LIGO’s first detection in 2015 set a precedent for rapid multi-facility alerts and organized follow-ups.

CHIME’s FRB alert system provides near-real-time notices that trigger radio and optical follow-up. That rapid-response model reduces false positives, improves localization, and yields richer contextual data about transient signals.

Automated scheduling and target-of-opportunity observations at major telescopes mean candidate signals get checked quickly, often by multiple instruments, which tightens the chain of evidence.

Scientific and Theoretical Breakthroughs

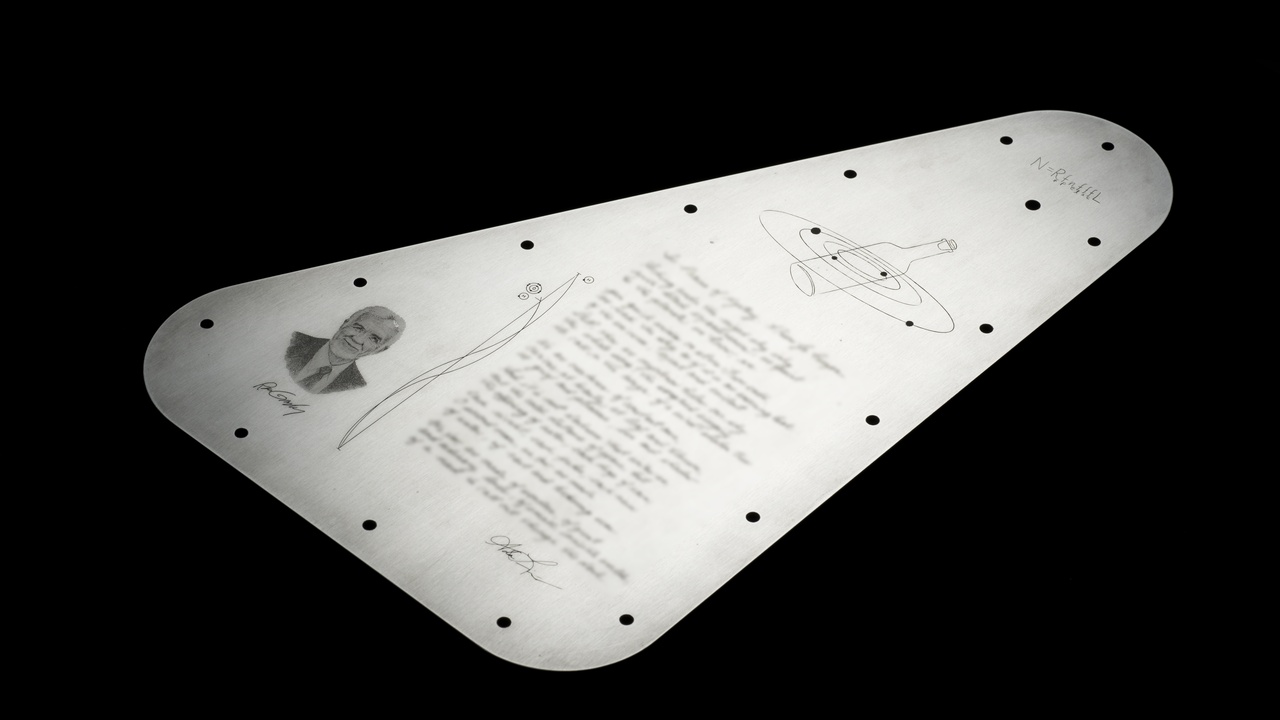

7. Refining the Drake Equation with data-driven constraints

Frank Drake wrote his famous equation in 1961 to frame the problem. For decades, many terms were pure guesswork. Kepler-era results changed that by supplying empirical numbers for the “fraction of stars with planets” term.

Current studies place the occurrence of small, rocky planets in Sun-like habitable zones in a range that begins around a few percent and extends higher (estimates often cite roughly 20–50% for various stellar types), depending on definitions and uncertainties.

Researchers now use Bayesian methods to propagate those uncertainties and produce probability distributions for communicative-civilization estimates, which helps prioritize searches and quantify any non-detection results.

8. Expanding technosignature concepts beyond narrowband radio

Observational anomalies led researchers to widen the range of testable technosignatures. Tabby’s Star (KIC 8462852), whose unusual dimming drew attention in 2015, prompted discussions about megastructures and other non-standard signatures.

Teams now consider atmospheric industrial pollutants (CFC analogs), waste-heat infrared excesses, and artificial illumination on planetary nightsides as concrete targets. Upcoming telescopes will be sensitive enough to place meaningful limits on some of these ideas.

Community involvement increases transparency and trust while creating unexpected pathways to discovery—sometimes a new set of eyes finds what automated pipelines miss.

Community involvement increases transparency and trust while creating unexpected pathways to discovery—sometimes a new set of eyes finds what automated pipelines miss.

Summary

- Advances in antenna arrays and receivers dramatically increased sensitivity and survey speed.

- Machine learning and large-scale pipelines let teams process petabyte datasets (Breakthrough Listen, 2015) and reduce false positives.

- Exoplanet discoveries (Kepler, TESS) shifted searches from blind scans to prioritized target lists.

- Technosignature thinking now spans radio, optical, infrared, and atmospheric diagnostics—prompted by anomalies like Tabby’s Star.

- Private funding and citizen science (SETI@home) expanded observing capacity, open data, and community scrutiny.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.