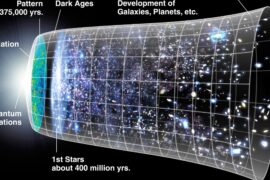

In 1992 astronomers announced the first confirmed planets beyond our solar system — but they weren’t orbiting a Sun-like star at all; they were circling a dead pulsar, upending expectations about where planets could exist.

Since that surprise and the Kepler mission’s launch in 2009 (followed by TESS in 2018 and JWST operations beginning in 2022), telescopes have turned up worlds that look and behave in ways our Solar System never prepared us for. Some drip molten rock, some swallow light like charcoal, and some orbit dead stars or two suns. These bizarre exoplanets matter because they expose gaps in formation and atmospheric theory and they spark the public imagination — who doesn’t want to know what iron rain or a planet hotter than a star would feel like?

The list below profiles 10 of the oddest, most puzzling examples; each entry explains what’s odd, which instruments delivered the evidence (Hubble, Kepler, HARPS, VLT, JWST and others), and why scientists are still debating what’s really going on.

Alien Atmospheres: Clouds, Rain, and Colors That Defy Expectation

Spectroscopy from Hubble, Spitzer and ground-based high-resolution instruments like HARPS and VLT has shown atmospheres filled with unexpected species — metal vapors, silicate clouds and extreme albedos — forcing new chemistry, condensation and circulation physics into exoplanet models. Some oddities are directly detected; others are inferred from colors and phase curves.

1. WASP-76b — iron rain and day–night chemistry

WASP-76b’s day side reaches temperatures hot enough to vaporize metals, which then condense as iron rain on the night side.

Discovered in 2016, this ultra-hot Jupiter orbits in roughly 1.8 days and has dayside temperatures around 2,400–2,600 K. High-resolution ground-based spectra (notably with HARPS and ESPRESSO on the VLT) revealed neutral iron and asymmetric line profiles that imply iron vapor being transported toward the cooler limb and night side.

Tidally locked circulation creates an extreme day–night temperature gradient, driving condensation and precipitation of refractory species like iron and silicates. Models struggle to reproduce the observed iron signal strength and velocity signatures, so WASP-76b is a testbed for atmospheric transport and cloud microphysics — areas JWST and VLT follow-ups are targeting.

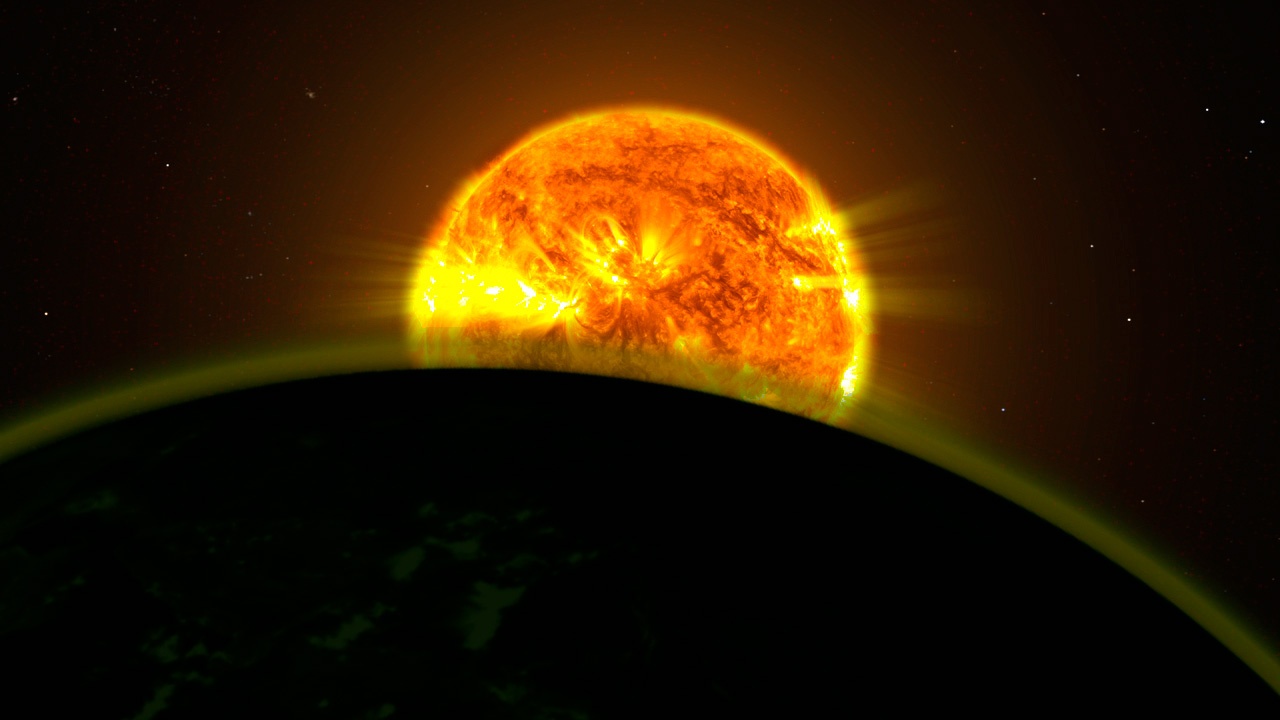

2. HD 189733b — a blue world where glass may fall from the sky

HD 189733b appears deep blue, but the color comes from high-altitude scattering and tiny silicate droplets — essentially microscopic glass — rather than oceans.

Discovered in 2005 and located about 64 light-years away, HD 189733b has a mass near 1.1 Jupiter masses. Hubble transmission spectra revealed high-altitude hazes and Rayleigh-like scattering that gives the planet its blue tint. Spitzer and Doppler studies inferred winds of several km/s across the atmosphere.

The ‘glass rain’ hypothesis posits that silicate vapors condense into tiny glassy droplets that remain lofted or fall depending on dynamics. That idea challenges cloud microphysics derived from Solar System practice and makes HD 189733b a benchmark for testing aerosol formation under intense irradiation.

3. TrES-2b — the blackest planet we’ve ever seen

TrES-2b reflects less than 1% of incoming visible light, making it darker than coal and the blackest exoplanet measured.

Discovered in 2006, TrES-2b’s geometric albedo was constrained by years of Kepler photometry to be under 1%. The long baseline of Kepler brightness measurements gives strong confidence in this result.

Possible explanations include strong optical absorbers (neutral sodium or other volatiles), light-absorbing aerosols, or a lack of reflective clouds. Atmospheric opacity models had to be extended significantly to try to reproduce such a low albedo, and TrES-2b remains a benchmark for understanding how atmospheres can trap—or fail to reflect—starlight.

Weird Compositions & Stripped Cores

Masses and radii from TESS, Kepler and radial-velocity campaigns reveal planets with surprising bulk compositions — from lava oceans to apparently exposed cores. These measurements force revisions to planet formation and photoevaporation timelines.

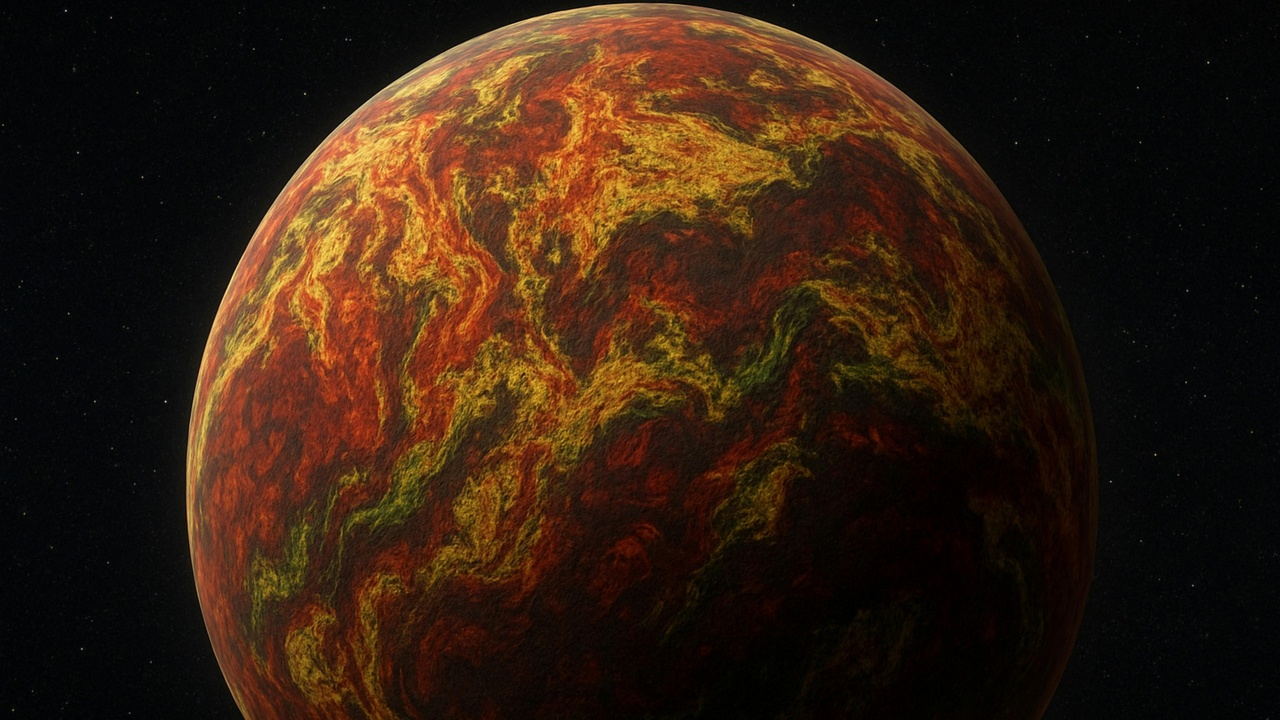

4. 55 Cancri e — a lava world (and maybe a diamond?)

55 Cancri e completes an orbit in less than a day and was once speculated to have a carbon-rich, ‘diamond’ interior.

First reported around 2004, 55 Cancri e has an orbital period of roughly 0.74 days and a mass near 8 Earth masses. Its high mean density and equilibrium temperatures estimated between about 2,000–2,700 K suggest a largely rocky composition and surface temperatures consistent with partial melting or a lava ocean.

The diamond interpretation depended sensitively on assumed stellar abundances and planet composition models; later work tempered that claim. JWST-era spectroscopy aims to detect any tenuous atmosphere and further constrain interior composition, helping decide whether 55 Cancri e is molten rock, a carbon-rich relic, or something in between.

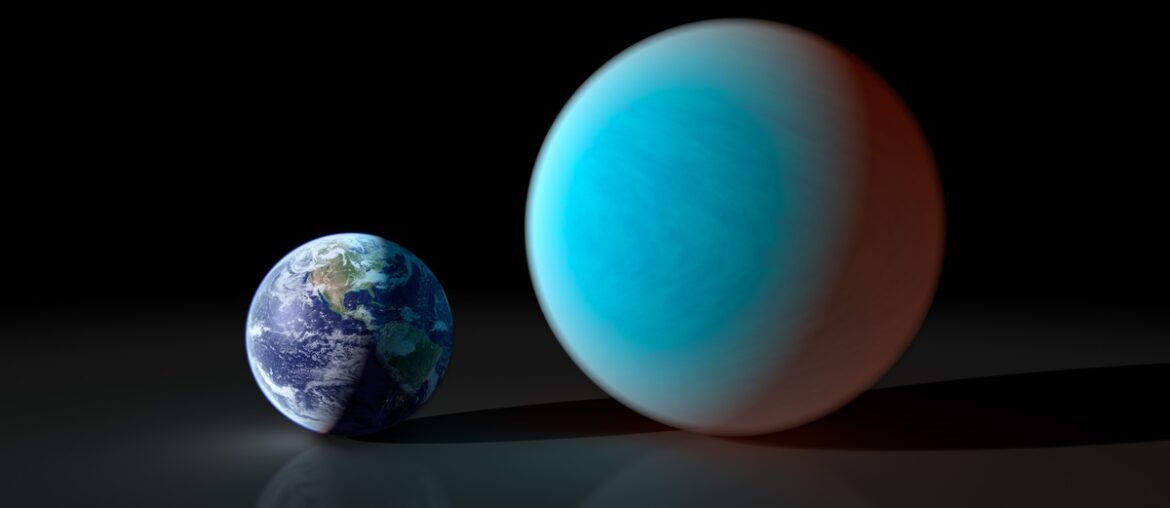

5. TOI-849b — a stripped gas-giant core in plain sight

TOI-849b looks like a Neptune-sized planet but carries the mass expected of a gas-giant core — almost as if its gaseous envelope was stripped away.

Discovered by TESS in 2020 with follow-up radial velocities, TOI-849b has a mass around 39 Earth masses and a radius near 3.4 Earth radii, orbiting in roughly 18.4 hours (≈0.77 days). That density is far higher than for a typical sub-Neptune, yet too low for a pure iron world.

Standard core-accretion models predict such massive cores should have accreted large envelopes; TOI-849b suggests violent history — runaway stripping by the star, giant impacts, or failed gas accretion. Labels like ‘chthonian’ have appeared in press and papers, and the planet is a crucial constraint on how and when cores grow and retain gas.

Odd Orbits and Strange Hosts: Planets Around Dead Stars and Two Suns

Where a planet orbits can be as strange as what it’s made of. Circumbinary worlds, planets that survived or re-formed after supernovae, and ultra-short-period rocks force dynamical and survival scenarios that rewrite migration and tidal theories. The 1992 pulsar planets discovery was a pivotal moment.

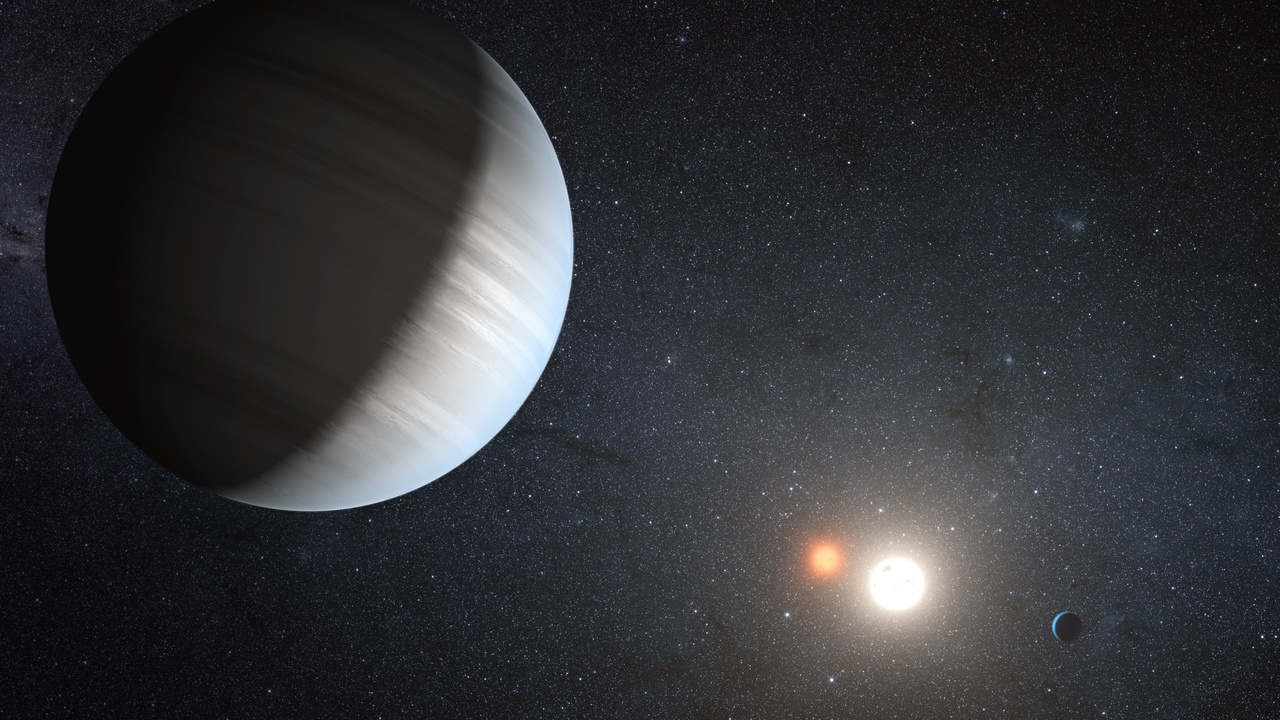

6. Kepler-16b — a true Tatooine, orbiting two suns

Kepler-16b orbits a pair of stars, producing changing illumination and the prospect of double sunsets much like fictional Tatooine.

Discovered by Kepler in 2011, Kepler-16b is roughly Saturn-sized and was detected because transits occur against an eclipsing binary — the planet’s transits and the binary’s eclipses produce a distinctive light curve. Transit timing and photometry allowed precise orbital characterization.

Circumbinary planets challenge models of disk stability and planetesimal growth in a varying gravitational potential, yet Kepler-16b validated predictions that planet formation can proceed in binary disks and opened up a whole class of unexpected orbital architectures.

7. Planets around PSR B1257+12 — survivors orbiting a dead star

In 1992 Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail announced planets orbiting the pulsar PSR B1257+12 — the first confirmed exoplanets, and they were around a dead, rapidly spinning neutron star.

Pulsar timing measurements, precise to microseconds, revealed two (or three, depending on definitions) planetary-mass companions. The detection method offered extraordinary precision and marked the field’s beginning.

The big puzzle: did those planets survive the supernova that created the pulsar or form later from a fallback disk? Both scenarios strain conventional formation theory and imply that planet formation and survival may be more robust — or more violent — than previously thought.

8. Kepler-78b — a rocky world that orbits in just hours

Kepler-78b orbits its star in roughly 8.5 hours, so a ‘year’ lasts less than a day on this tiny, intensely irradiated world.

Discovered in 2013 via Kepler transits and confirmed with ground-based radial velocities, Kepler-78b has an Earth-like bulk density despite being extremely close to its star (orbital period ≈8.5 hours). It thus survives at distances where tidal forces and heating are extreme.

How a small rocky planet ends up so close — without being tidally disrupted or stripped of its mantle — challenges migration and tidal-dissipation models. Ultra-short-period planets like Kepler-78b are key constraints on how tides, migration, and stellar interactions sculpt planetary systems.

Ultra-hot Worlds: Temperatures Hotter Than Stars and Disintegrating Planets

Some planets sit so close to their stars that atoms are stripped from the atmosphere, molecules dissociate, and mass loss can produce comet-like tails. These extremes bridge planetary and stellar physics and let us observe high-energy processes in action.

9. KELT-9b — the planet hotter than some stars

KELT-9b’s dayside reaches roughly 4,100–4,600 K, temperatures hotter than many K-type stars and hot enough to ionize metals in the atmosphere.

Discovered by the KELT survey in 2017, KELT-9b orbits in about 1.5 days around a very hot host. Spectroscopy has revealed atomic and ionized metals — signatures that molecules are thermally dissociated and that opacity sources differ from cooler hot Jupiters.

These conditions produce extreme atmospheric escape and unique spectral fingerprints, providing a laboratory where stellar-like physics mixes with planetary structure. KELT-9b helps test models of irradiated atmospheres and star–planet interaction under the most extreme irradiation regimes.

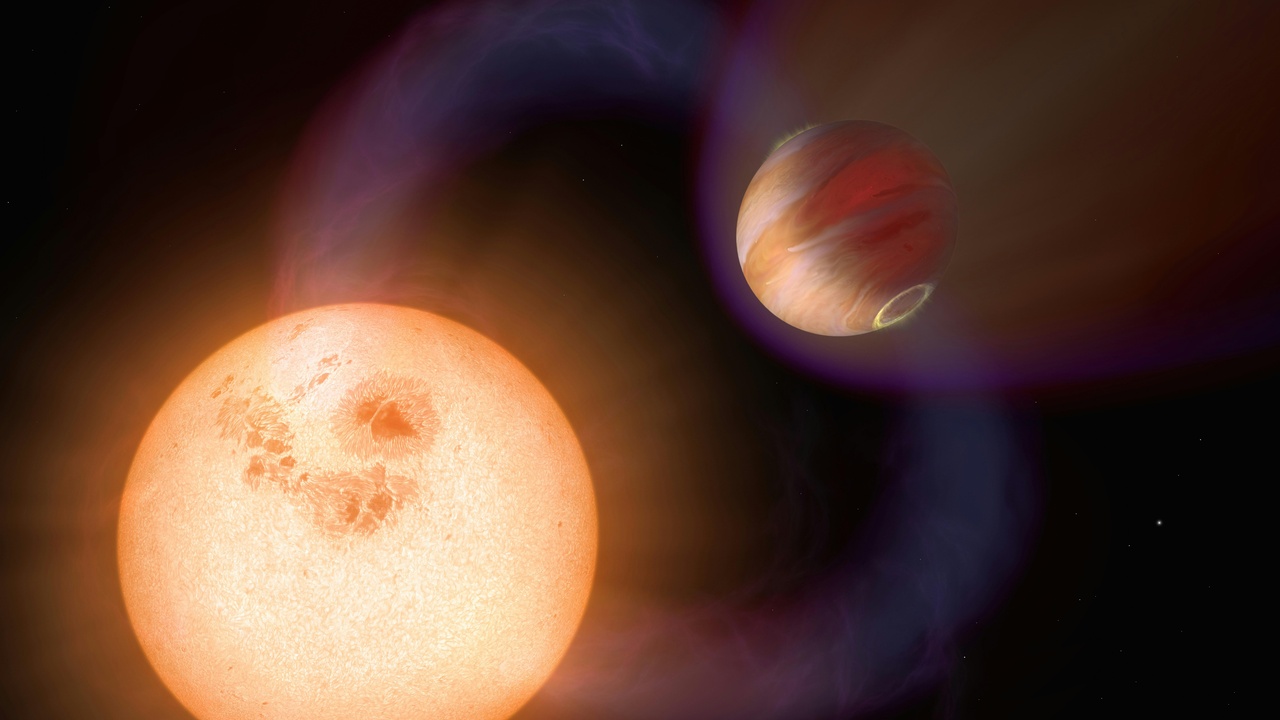

10. WASP-12b — a planet being pulled apart by its star

WASP-12b is so close to its host star that it’s losing mass and forming an extended, comet-like envelope.

Discovered in 2008 as a hot Jupiter with an orbital period near 1.1 days, WASP-12b shows observational signatures of mass loss: excess absorption in ultraviolet and optical lines and an extended gas envelope detected with Hubble and ground-based instruments. Some studies even suggest orbital decay on observable timescales.

Hints of unusual atmospheric chemistry, including carbon-rich interpretations, add to the puzzle. WASP-12b forces us to model mass transfer, tidal evolution and the ultimate fate of close-in giants — will they be engulfed, or will they donate material to their stars?

Summary

- Exoplanet diversity has shattered simple expectations: discoveries since the pulsar planets in 1992 and Kepler’s 2009 survey (with follow-ups from TESS and JWST) reveal worlds with iron rain, silicate hazes, and daysides as hot as stars.

- Atmospheric spectroscopy (Hubble, VLT/HARPS, JWST) and precise mass–radius measurements show that composition, cloud microphysics, and extreme irradiation regimes require new physics in our models.

- Unusual orbits — circumbinary planets like Kepler-16b, pulsar companions discovered in 1992, and ultra-short-period rocks such as Kepler-78b — force revisions to formation, migration and tidal theories.

- Planets on the edge of destruction (WASP-12b, TOI-849b, KELT-9b) are natural laboratories for atmospheric escape, star–planet interaction, and core-formation pathways.

- Upcoming and ongoing observations with JWST, ELTs and new radial-velocity campaigns promise to resolve many puzzles and undoubtedly reveal more strange planets — keep an eye on results from NASA, ESA and the major observatories.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.