On July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 landed on the Moon — a single event that rewired public imagination and fed a century of stories blending real astronomy with fiction.

That moment shows how discoveries and missions shape not just science but the stories we tell about the cosmos, and why the cross-talk matters: accurate astronomy can sharpen plausibility, ramp up public interest, steer technology, and create cultural metaphors that stick.

Below I unpack eight distinct ways that scientific astronomy influence storytelling, grouped into three categories — scientific foundations, technological plausibility and design, and storytelling and cultural imagery — to show how data and pictures become plot, gadget, and meaning.

Scientific Foundations: How Astronomy Shapes Questions and Accuracy

Astronomy supplies empirical findings, specialized vocabulary, and the open scientific questions authors dramatize. Accurate science draws readers who know enough to notice sloppiness, and it gives writers a launchpad of real puzzles to fictionalize.

1. Inspiring Real Scientific Questions

Astronomy hands authors the core puzzles they dramatize: origins of life, habitability, dark matter, and planetary formation all read like built-in mysteries. The 1995 discovery of 51 Pegasi b opened a floodgate; by 2024 there were over 5,500 confirmed exoplanets and a thousand narrative permutations for habitable worlds.

Series such as The Expanse borrow realistic orbital mechanics to build tension around travel time and resource management, while Kepler and TESS discoveries supplied fresh setting ideas that propelled dozens of novels and outreach pieces. And public enthusiasm for exoplanets has fed funding and outreach that keep new discoveries in the news — which in turn renews fiction’s well of ideas.

As a planetary scientist might observe, preliminary data create fertile speculative space for authors and educators to engage the public about what’s plausible and what’s pure invention.

2. Supplying Accurate Detail and Scientific Terms

Astronomy gives writers a vocabulary that anchors speculative worlds: spectroscopy, habitable zone, red dwarf, escape velocity — those terms lend texture and credibility. Arthur C. Clarke’s 1945 suggestion of geostationary satellites is a classic example of scientific thinking seeding fiction and later engineering.

Contemporary authors lean on those terms to teach while entertaining; Andy Weir’s The Martian (2011) uses chemistry, orbital mechanics, and resource math so readers learn as they root for the protagonist. Neal Stephenson likewise embeds technical scaffolding to reward curious readers without turning the plot into a textbook.

Educators often assign scientifically grounded fiction precisely because accurate detail lowers the barrier for explaining real concepts in classrooms and public talks.

3. Providing Data That Suggests New Speculation

Raw astronomical anomalies become narrative seeds: odd light curves, unexplained radio bursts, and tentative biosignature hints invite fictional escalation. The 1977 “Wow!” signal remains a tidy prompt for mysteries, and fast radio bursts (FRBs) discovered in the 2000s–2010s have spawned numerous short stories and novels centered on strange transmissions.

Authors take tentative or ambiguous observations and ask “what if?” — what if that signal had a pattern, or a biosignature later proved ambiguous? Scientists investigate anomalies; writers imagine outcomes and societal responses, turning preliminary data into ethical dramas and suspense plots.

Technology, Design, and Plausibility: Turning Observations into Gadgets

Astronomical research sets engineering constraints and aesthetic reference points that shape fictional tech. Sometimes fiction predicts engineering advances, and sometimes it borrows the look and ergonomics of real instruments to sell an imagined device.

4. Predicting Real Engineering Solutions

Authors have a history of prototyping solutions on the page. Arthur C. Clarke’s 1945 treatment of geostationary satellites prefigured telecommunications that followed decades later, and modern private firms such as SpaceX (founded 2002) now realize launch economies that were once the stuff of pulp and magazine speculation.

Fictional communicators and compact user devices inspired early mobile-phone designers, and depictions of propulsion systems — ion drives, nuclear thermal concepts — have spurred public conversations about which technologies deserve research dollars. Engineers sometimes cite sci‑fi prototypes as motivational shorthand when pitching concepts.

So fiction can function as conceptual prototyping: an accessible way to test ideas before funding, fabrication, or policy debates begin in earnest.

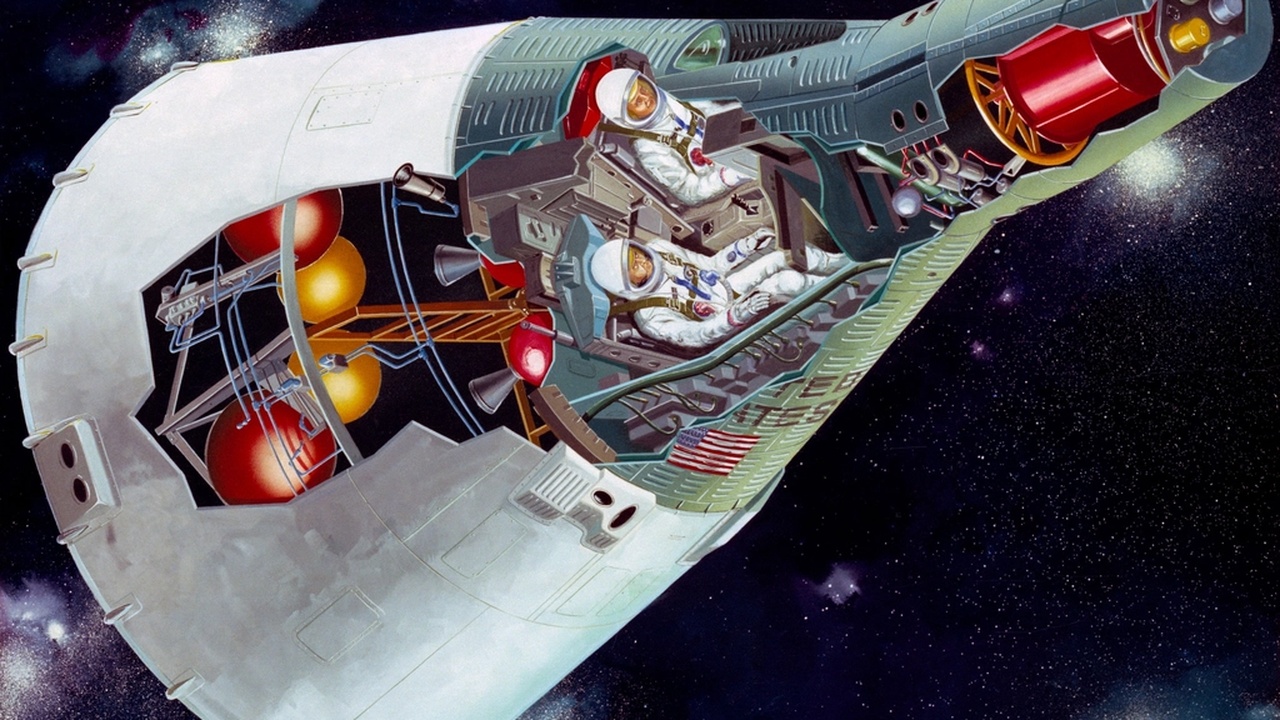

5. Human Factors, Interfaces, and UX Borrowed from Fiction

Writers and filmmakers imagine interfaces—voice control, heads-up displays, gesture UIs—that designers then evaluate for usability. Star Trek (1960s) popularized touchscreens and communicators; engineers at companies like Apple and Google have repeatedly noted science fiction as an influence in interviews.

NASA prototypes for cockpit HUDs and augmented-reality overlays borrow the cultural vocabulary viewers expect from screens and helmets. Fictional UIs provide test cases for human factors: how crews might read alerts during a solar flare, or how an astronaut’s glove limits fine manipulation.

Public familiarity with those fictional interfaces often eases adoption when the real tech arrives, because fewer training hours are needed to translate familiar metaphors into real interactions.

6. Robotics, Materials, and Realistic Constraints

Astronomy highlights constraints — radiation, vacuum, extreme temperatures — that force believable engineering choices in fiction. Mars rovers provide vivid, real-world models: Sojourner (1997), Curiosity (2012), and Perseverance (2021) show how mobility, autonomy, and instrument trade-offs play out.

Those missions influence robotic characters and tools in stories: realistic limits on power, latency, and repairability make for stronger drama than omnipotent robots. Material science advances such as modern heat shields and carbon composites also let authors imagine gear that feels possible without violating physics.

Authors who respect those constraints craft more convincing tech — and that plausibility matters to readers who work in engineering or follow NASA missions closely.

Storytelling, Themes, and Cultural Imagery

Astronomy supplies metaphors of scale, visual cues, and mission narratives that authors turn into character arcs and social commentary. Real missions inform the cultural processing of exploration, and images from telescopes become a shared visual language for filmmakers and cover artists.

7. Themes of Scale, Wonder, and Ethical Questions

The sheer scales astronomy evokes — planetary, stellar, galactic — push writers to probe meaning, stewardship, and ethics. Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965) uses planetary ecology to interrogate politics and resource control, and many films after Apollo emphasized human vulnerability against vast space backdrops.

Those themes map directly onto contemporary debates: planetary protection protocols, the ethics of asteroid mining, and the morality of terraforming are frequent plot engines. Fiction lets readers play out long-term consequences faster than policy cycles do, and it often frames public attitudes toward real decisions.

So astronomy’s scale doesn’t just awe readers — it forces them, via story, to consider responsibilities that scientists and policymakers wrestle with in real time.

8. Visual Language and Public Fascination

Astronomical images and mission footage create a visual vocabulary filmmakers and artists borrow. Hubble’s Deep Field (1995) re-framed how audiences imagine deep space, and the James Webb Space Telescope’s first images in 2022 supplied new textures and color palettes that show up in modern cinematography and cover art.

Star Wars (1977) helped codify space-opera aesthetics — dramatic planetary vistas, weathered starships, and scale cues — while more recent films and book covers have leaned on JWST-inspired nebular colors and lunar panoramas to sell authenticity.

Designers use real astronomical textures because photographic realism improves immersion; audiences intuitively accept images rooted in real missions as more believable, even when the story itself is speculative.

Summary

- Astronomy provides concrete discoveries, terms, and anomalies (51 Pegasi b in 1995; the 1977 “Wow!” signal; over 5,500 exoplanets as of 2024) that authors turn into central plot engines.

- Technical detail and constraints—from Clarke’s 1945 geostationary idea to Mars rovers (Sojourner 1997; Curiosity 2012; Perseverance 2021)—make gadgets and characters feel authentic and usable as narrative devices.

- Visual milestones (Hubble Deep Field 1995, JWST first images 2022, Apollo 11 on July 20, 1969) form a shared visual and emotional vocabulary that designers and writers borrow to heighten immersion.

- There’s a two-way influence: engineers and agencies cite fiction when imagining interfaces and missions, while scientific astronomy supplies the data and constraints that keep stories plausible.

- Watch the skies and read widely: tracking NASA releases or revisiting novels from Clarke to contemporary writers will reveal how astronomy in science fiction continues to shape both imagination and innovation.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.