In the 1800s, observatories from Greenwich to the Andes reshaped how we map the sky: better telescopes, spectroscopy and photographic plates turned scattered observations into systematic science. That era set the stage for modern astrophysics and a lively international community of researchers.

There are 48 19th century astronomers, ranging from Anders Jonas Ångström to Édouard Roche. For each person you’ll find below the columns Lifespan (years), Nationality, Main role or discovery (max 15 words), organized so you can scan careers, origins and key contributions — you’ll find below the full list.

How were the names chosen for this list?

The list focuses on astronomers active in the 19th century who made identifiable contributions (discoveries, instruments, methods or influential publications), aiming for geographic and disciplinary breadth rather than exhaustive inclusion of every contemporary practitioner.

How can I use the Lifespan, Nationality and Main role columns for research?

Use lifespan to place discoveries in chronological context, nationality to explore institutional or regional trends, and the concise role/descovery field to quickly filter for topics (planetary, stellar, instrumentation) before digging into primary sources.

19th Century Astronomers

| Name | Lifespan (years) | Nationality | Main role or discovery (max 15 words) |

|---|---|---|---|

| William Herschel | 1738–1822 | German-British | Discovered infrared radiation (1800); cataloged thousands of deep-sky objects. |

| Caroline Herschel | 1750–1848 | German-British | Discovered several comets; was the first woman paid for scientific work. |

| Giuseppe Piazzi | 1746–1826 | Italian | Discovered Ceres, the first asteroid, on January 1, 1801. |

| Friedrich Bessel | 1784–1846 | German | First person to measure the parallax of a star (61 Cygni). |

| Carl Friedrich Gauss | 1777–1855 | German | Developed a method to calculate the orbit of Ceres from few observations. |

| Heinrich Olbers | 1758–1840 | German | Discovered asteroids Pallas and Vesta; formulated Olbers’ paradox. |

| Joseph von Fraunhofer | 1787–1826 | German | Discovered dark absorption lines in the Sun’s spectrum (Fraunhofer lines). |

| John Herschel | 1792–1871 | British | Extended his father’s sky surveys to the Southern Hemisphere; invented the cyanotype. |

| Wilhelm Struve | 1793–1864 | German-Russian | Conducted extensive surveys of double stars, cataloging over 3,000 pairs. |

| Friedrich Argelander | 1799–1875 | German | Created the Bonner Durchmusterung, a massive catalog of 324,198 stars. |

| Lord Rosse | 1800–1867 | Irish | Built the “Leviathan of Parsonstown” telescope and discovered spiral structure in galaxies. |

| George Airy | 1801–1892 | British | Astronomer Royal for 46 years; established Greenwich as the prime meridian. |

| Christian Doppler | 1803–1853 | Austrian | Described the Doppler effect, the change in frequency of a wave for a moving source. |

| Urbain Le Verrier | 1811–1877 | French | Predicted the existence and location of Neptune using only mathematics. |

| Johann Galle | 1812–1910 | German | First person to observe and identify Neptune, based on Le Verrier’s calculations. |

| Anders Jonas Ångström | 1814–1874 | Swedish | Pioneered spectroscopy; the ångström unit of length is named for him. |

| Maria Mitchell | 1818–1889 | American | First American woman to work as a professional astronomer; discovered a comet. |

| Angelo Secchi | 1818–1878 | Italian | A pioneer of astronomical spectroscopy; one of the first to classify stars by spectra. |

| Léon Foucault | 1819–1868 | French | Demonstrated the Earth’s rotation with his famous pendulum experiment. |

| John Couch Adams | 1819–1892 | British | Independently predicted the existence and location of Neptune from Uranus’s orbit. |

| William Huggins | 1824–1910 | British | Pioneered spectroscopy, showing some nebulae were gas and not collections of stars. |

| Jules Janssen | 1824–1907 | French | Co-discovered helium in the Sun’s spectrum; pioneered solar eclipse expeditions. |

| Asaph Hall | 1829–1907 | American | Discovered the two moons of Mars, Phobos and Deimos, in 1877. |

| James Clerk Maxwell | 1831–1879 | Scottish | Theoretically demonstrated that Saturn’s rings must be composed of many small particles. |

| Giovanni Schiaparelli | 1835–1910 | Italian | Created detailed maps of Mars, describing linear features as “canali” (channels). |

| Simon Newcomb | 1835–1909 | Canadian-American | Calculated planetary motions and fundamental astronomical constants with high precision. |

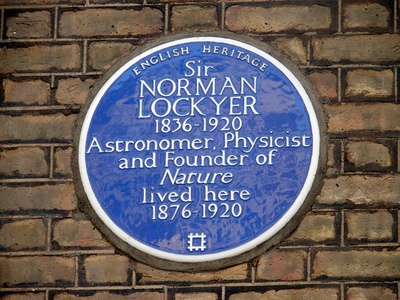

| Norman Lockyer | 1836–1920 | British | Co-discovered the element helium by observing the Sun’s spectrum. |

| Henry Draper | 1837–1882 | American | Pioneered astrophotography, obtaining the first photograph of a stellar spectrum. |

| Camille Flammarion | 1842–1925 | French | Prolific author and popularizer of astronomy; studied double stars and Mars. |

| David Gill | 1843–1914 | Scottish | Used astrophotography for parallax measurements and directed the Cape Photographic Durchmusterung. |

| George Darwin | 1845–1912 | British | Studied the tidal evolution of the Earth-Moon system. |

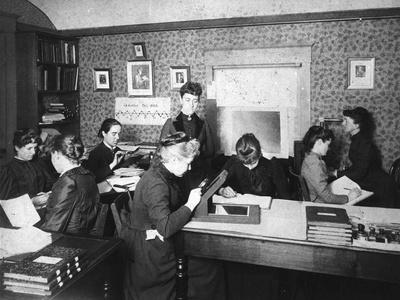

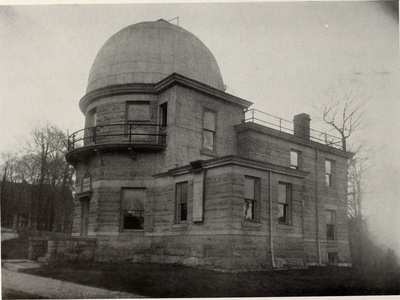

| Edward Pickering | 1846–1919 | American | Director of Harvard Observatory; pioneered photographic photometry and spectral surveys. |

| Seth Carlo Chandler | 1846–1913 | American | Discovered the “Chandler wobble,” a small variation in Earth’s axis of rotation. |

| Percival Lowell | 1855–1916 | American | Championed the theory of Martian canals built by an intelligent civilization. |

| Edward Emerson Barnard | 1857–1923 | American | Discovered Jupiter’s fifth moon, Amalthea, and was a pioneer of astrophotography. |

| Williamina Fleming | 1857–1911 | Scottish-American | Cataloged over 10,000 stars; discovered the Horsehead Nebula. |

| James Edward Keeler | 1857–1900 | American | Spectroscopically proved that Saturn’s rings are made of small, orbiting particles. |

| Max Wolf | 1863–1932 | German | Pioneered the use of astrophotography to discover asteroids. |

| Annie Jump Cannon | 1863–1941 | American | Developed the Harvard spectral classification system (O, B, A, F, G, K, M). |

| Antonia Maury | 1866–1952 | American | Developed a detailed stellar classification system that noted spectral line sharpness. |

| George Ellery Hale | 1868–1938 | American | Invented the spectroheliograph; founded Yerkes and Mount Wilson Observatories. |

| Henrietta Swan Leavitt | 1868–1921 | American | Discovered the period-luminosity relationship in Cepheid variable stars. |

| Mary Somerville | 1780–1872 | Scottish | Science writer and polymath whose books popularized 19th-century astronomy. |

| Heinrich Schwabe | 1789–1875 | German | Discovered the approximately 11-year cycle of sunspot activity. |

| Thomas Henderson | 1798–1844 | Scottish | First person to measure the parallax of Alpha Centauri. |

| Édouard Roche | 1820–1883 | French | Calculated the Roche limit, the distance a satellite can approach before being torn apart. |

| Lewis Swift | 1820–1913 | American | A prolific discoverer of comets and nebulae, often using homemade telescopes. |

| Warren De La Rue | 1815–1889 | British | A wealthy amateur who pioneered the use of photography in astronomy. |

Images and Descriptions

William Herschel

A towering figure who straddled two centuries, Herschel built powerful telescopes, discovered the planet Uranus (1781), and created extensive catalogs of nebulae and double stars, mapping the structure of the Milky Way.

Caroline Herschel

Working alongside her brother William, Caroline was a formidable astronomer. She discovered numerous comets and nebulae, meticulously updated star catalogs, and was the first woman in England to earn a government salary for her scientific contributions.

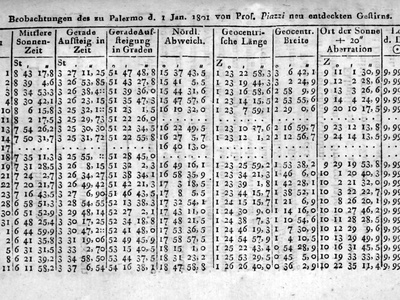

Giuseppe Piazzi

Piazzi kicked off 19th-century astronomy by discovering Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt. He initially thought it was a comet, but its regular orbit proved it was a new type of celestial body, which we now call a dwarf planet.

Friedrich Bessel

Bessel solved one of astronomy’s oldest problems by making the first reliable measurement of a star’s distance. This confirmed the vast scale of the universe and solidified the heliocentric model, opening the door to understanding cosmic distances.

Carl Friedrich Gauss

While primarily a mathematician, Gauss made a pivotal astronomical contribution. When Piazzi lost track of the newly discovered Ceres, Gauss invented a powerful new method for orbit calculation that allowed astronomers to find it again.

Heinrich Olbers

A physician and astronomer, Olbers discovered two of the first four asteroids, Pallas and Vesta. He is also famous for his paradox, which asks why the night sky is dark if the universe is infinite and filled with stars.

Joseph von Fraunhofer

An optician and physicist, Fraunhofer’s meticulous study of the solar spectrum revealed hundreds of dark lines. These “Fraunhofer lines” were later found to be the chemical fingerprints of elements in the Sun’s atmosphere, birthing astrophysics.

John Herschel

The son of William Herschel, John was a polymath who made major contributions to astronomy. He spent years in South Africa systematically cataloging the stars, nebulae, and star clusters of the southern sky, completing his father’s survey.

Wilhelm Struve

As the director of the Dorpat and then Pulkovo Observatories, Struve was a leading authority on double stars. His meticulous surveys and catalogs provided crucial data for understanding stellar evolution and measuring stellar parallax.

Friedrich Argelander

Argelander undertook one of the most ambitious projects of his time: cataloging the position and brightness of every visible star in the northern sky. The resulting Bonner Durchmusterung was a foundational reference for astronomers for decades.

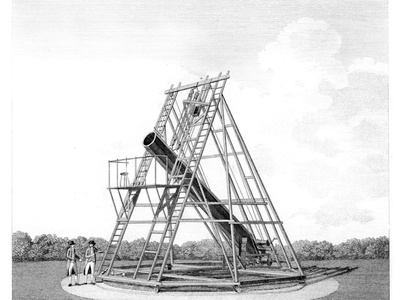

Lord Rosse

William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse, built the largest telescope in the world in the 1840s. With its 72-inch mirror, he was the first to resolve and sketch the spiral structure of what were then called “spiral nebulae.”

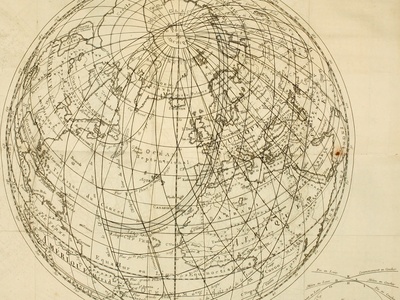

George Airy

As the long-serving seventh Astronomer Royal, Airy modernized the Royal Greenwich Observatory. He is best known for establishing Greenwich as the location of the Prime Meridian (0° longitude), which became the international standard in 1884.

Christian Doppler

Doppler proposed that the observed frequency of light and sound waves changes if the source and observer are moving relative to one another. This “Doppler effect” became a fundamental tool in astronomy for measuring the radial velocity of stars.

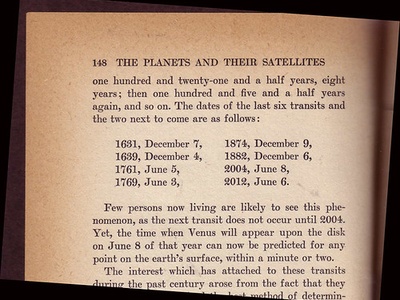

Urbain Le Verrier

A master of celestial mechanics, Le Verrier famously predicted Neptune’s position by analyzing irregularities in Uranus’s orbit. His calculations led directly to the planet’s discovery in 1846, a stunning triumph for gravitational theory.

Johann Galle

Galle was the astronomer at the Berlin Observatory who received Le Verrier’s letter predicting Neptune’s location. That very night in 1846, he pointed his telescope to the specified coordinates and found the new planet, confirming the prediction.

Anders Jonas Ångström

Ångström was a founder of spectroscopy, proving that hot gas emits light at the same frequencies it absorbs when cool. He created detailed maps of the solar spectrum, and the ångström (10⁻¹⁰ meters), a unit used to measure light wavelengths, honors his work.

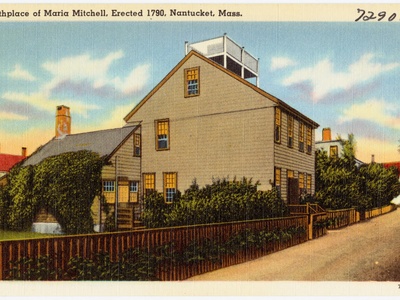

Maria Mitchell

Mitchell gained international fame after discovering “Miss Mitchell’s Comet” in 1847. She became the first professor of astronomy at Vassar College and a trailblazer for women in science in the United States.

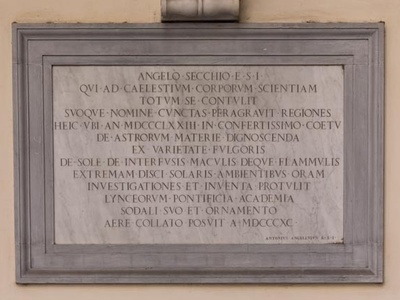

Angelo Secchi

A Jesuit priest and director of the Vatican Observatory, Secchi was a trailblazer in classifying stars based on their spectra. He created one of the first spectral classification systems, grouping stars into four types, a foundational step for modern astrophysics.

Léon Foucault

Foucault provided the first simple, direct proof of the Earth’s rotation. His large pendulum, suspended in the Panthéon in Paris in 1851, appeared to rotate its plane of swing over time, a clear visual demonstration of the planet turning beneath it.

John Couch Adams

Adams independently made the same mathematical prediction as Le Verrier about an unseen planet (Neptune) tugging on Uranus. Though his work wasn’t acted upon in time for the discovery, he is co-credited with the planet’s prediction.

William Huggins

Huggins analyzed the light from stars and nebulae with a spectroscope. He proved that some nebulae were vast clouds of gas, not unresolved collections of distant stars, and showed that stars contained the same elements found on Earth.

Jules Janssen

Janssen was an intrepid astronomer who traveled the world to observe solar eclipses. In 1868, he independently observed the same unknown spectral line as Norman Lockyer, leading to their co-discovery of the element helium in the Sun.

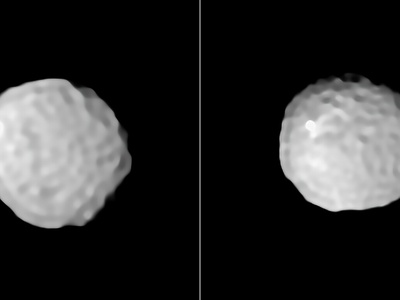

Asaph Hall

While working at the U.S. Naval Observatory, Hall conducted a systematic search for Martian moons. His persistence paid off with the discovery of both Phobos and Deimos, ending a long quest by astronomers for satellites around the Red Planet.

James Clerk Maxwell

Best known for his equations of electromagnetism, Maxwell also won the Adams Prize in 1857 for his mathematical work on Saturn’s rings. He proved that a solid or liquid ring would be unstable, concluding they must consist of countless small, disconnected particles.

Giovanni Schiaparelli

Schiaparelli was a meticulous observer of Mars, producing some of the first detailed maps of its surface. His observation of “canali” was mistranslated as “canals,” sparking widespread speculation about intelligent life and Martian civilizations.

Simon Newcomb

Newcomb was a mathematical astronomer who produced highly accurate tables of astronomical data. His precise calculations of planetary orbits and constants like the speed of light were used as international standards for much of the 20th century.

Norman Lockyer

While studying the Sun’s chromosphere during an eclipse in 1868, Lockyer observed a spectral line that didn’t correspond to any known element. He proposed it was a new element, which he named helium, decades before it was found on Earth.

Henry Draper

A physician and amateur astronomer, Draper was a master of astrophotography. In 1872, he took the first photograph showing absorption lines in a star’s (Vega) spectrum, and later the first detailed photo of the Orion Nebula, opening new avenues for research.

Camille Flammarion

Flammarion was one of the great communicators of 19th-century astronomy. His beautifully illustrated and accessible books inspired millions. He also founded his own observatory to conduct research on double stars, the Moon, and Mars.

David Gill

As Her Majesty’s Astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope, Gill was an advocate for using photography for precise measurements. He used photos of an asteroid to help determine the solar system’s scale and led a massive photographic survey of the southern sky.

George Darwin

The son of naturalist Charles Darwin, George Darwin applied mathematics to astronomical problems. He developed the theory that the Moon was once part of the Earth and had been thrown off, slowly receding due to tidal forces—a foundational idea in planetary science.

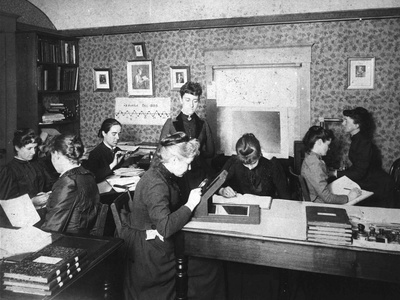

Edward Pickering

As director of the Harvard College Observatory, Pickering led massive projects to photograph the entire sky and analyze stellar spectra. He hired a team of women, known as the “Harvard Computers,” to perform the meticulous classification work.

Seth Carlo Chandler

Chandler found a slight, unexpected wobble in the Earth’s axis with a period of about 14 months. This deviation from the predicted rotational behavior, now known as the Chandler wobble, demonstrated that the Earth is not a perfectly rigid body.

Percival Lowell

Inspired by Schiaparelli, Lowell founded the Lowell Observatory in Arizona to study Mars. He became the most famous proponent of the idea that Martian canals were artificial structures, a theory that captivated the public but was later disproven.

Edward Emerson Barnard

A gifted observational astronomer, Barnard discovered Amalthea, the first moon of Jupiter found since Galileo’s time. He was also a master of astrophotography, creating stunning wide-field images of the Milky Way and cataloging dark nebulae.

Williamina Fleming

Originally a maid at the Harvard College Observatory, Fleming became a leader of the “Harvard Computers.” She developed a new stellar classification system, discovered hundreds of variable stars and novae, and is credited with discovering the iconic Horsehead Nebula.

James Edward Keeler

Using the Doppler effect, Keeler measured the speed of different parts of Saturn’s rings. He showed that the inner parts rotated faster than the outer parts, providing definitive proof that the rings were not solid but composed of countless individual particles.

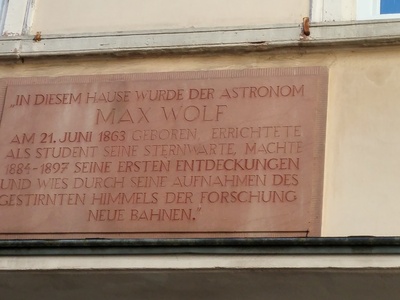

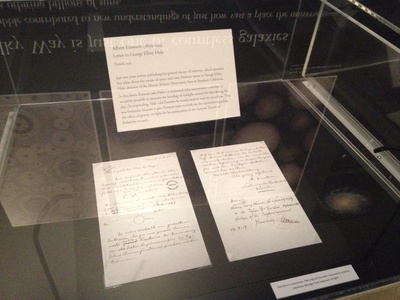

Max Wolf

Wolf revolutionized the search for asteroids by applying wide-field photography. Instead of painstakingly scanning the sky by eye, he took long exposures where asteroids appeared as streaks against the background stars, leading him to discover over 200.

Annie Jump Cannon

A key member of the Harvard Computers, Cannon developed the stellar classification system still used today. Her method was so efficient she could classify hundreds of stars per hour, ultimately cataloging the spectral types for over 350,000 stars.

Antonia Maury

A member of the “Harvard Computers,” Maury created a highly detailed but complex stellar classification scheme. Her system, which noted subtle differences in spectral lines, was later recognized as corresponding to the luminosity and size of stars (giants vs. dwarfs).

George Ellery Hale

Hale was a visionary solar astronomer and institution builder. He invented the spectroheliograph to photograph the Sun in specific wavelengths and was the driving force behind the creation of the world’s largest telescopes at Yerkes and Mount Wilson.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt

Leavitt’s work at the Harvard College Observatory led to a monumental discovery. She found a direct relationship between the brightness of Cepheid variable stars and the time they took to pulse, providing a “standard candle” to measure cosmic distances.

Mary Somerville

Somerville was a brilliant science communicator whose translations and original works made complex astronomical concepts accessible. She was one of the first two women admitted to the Royal Astronomical Society.

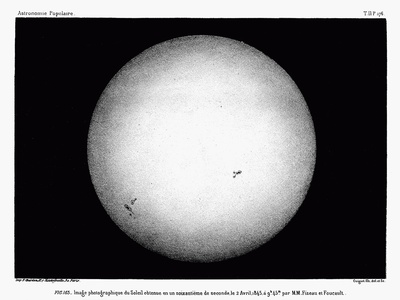

Heinrich Schwabe

An amateur astronomer, Schwabe patiently observed and recorded sunspots for 17 years, hoping to find a planet inside Mercury’s orbit. Instead, he discovered that the number of sunspots rose and fell in a regular cycle, now known as the solar cycle.

Thomas Henderson

Though Friedrich Bessel published his parallax results first, Henderson was the first to actually measure the parallax of a star, Alpha Centauri. His work from the Cape of Good Hope, along with Bessel’s, provided the first measurements of interstellar distances.

Édouard Roche

Roche was a mathematical astronomer known for his work on celestial mechanics. He calculated the theoretical distance, now called the Roche limit, within which a celestial body held together only by its own gravity will be destroyed by a second body’s tidal forces.

Lewis Swift

Despite humble beginnings and a lack of formal education, Swift became one of America’s most famous comet hunters. He discovered or co-discovered numerous comets, including the parent body of the Perseid meteor shower, Comet Swift-Tuttle.

Warren De La Rue

De La Rue was a key figure in the development of astrophotography. He produced some of the earliest and best photographs of the Moon in the 1850s and invented the photoheliograph to take daily pictures of the Sun.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.